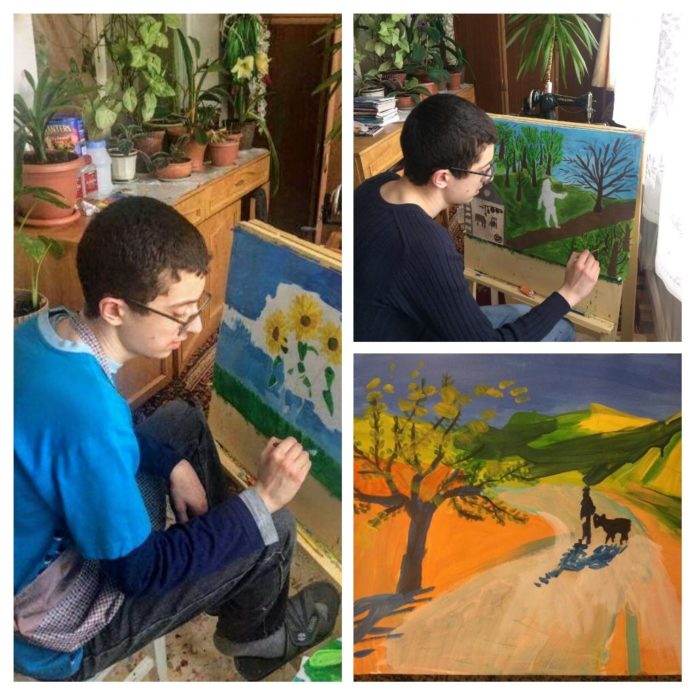

Edwin Hovsepyan at work

Bridging Social Distancing for People with Autism

by Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

YEREVAN, MAY 18, 2020 – If you think teaching music dance and art online is a challenge, consider what faces educators whose students are children and youngsters with autism. The My Way Socio-Rehabilitation Center for Children and Teenagers with Autism in Yerevan provides education and therapy for such pupils with special needs, usually with a full week’s schedule of classes in their spacious buildings. When the pandemic crisis hit Armenia in March, the center was functioning, but soon had to close, like other schools, first for a brief pause, then for an indefinite period of time.

“We immediately started to brainstorm,” Sona Petrosyan, co-founder and board member, explained, “and came up with online ideas.” The staff had to take into consideration the individual capabilities of each pupil, and to expect an uneven performance. This meant, they had to come up with “custom-tailored assignments,” Petrosyan said, “short and realistic, taking into account all the peculiarities and limitations, and, most importantly, the interests of our students.” They came up with a plan which provides almost all the students with 3-4 assignments per day, “through videos and audios, calls and materials, offline and online, even individuals and in groups using various applications.”

Eva Ghazanchyan made posters

for International Autism Awareness Day (April 2)

Music plays a very important role in My Way’s curriculum, and is a central feature of this new online learning project. The music therapists are recording videos for their pupils, selecting material appropriate for the age and individual interests of the students. They are using not only material the students are familiar with, but new pieces, and are engaging students in the teaching process. “My son Raphael,” Petrosyan said, “sang along with music therapist Marine Meliqsetyan; they selected songs for smaller classes with younger children, announcing the subject of the video in advance.” Another therapist Nara Sargsyan, organized a video with musical and physical therapy assignments, in which she engaged her daughter to sing and to demonstrate the movements. Children watching the video, either in small groups or singly, will follow the music and movements, and try to reproduce them. This is called “modeling.”

Vardan and Raphael

perform their piano duet at a distance

Raphael and his piano partner Vardan played a duet at a distance, on video. Or, Vardan would play the Armenian song Araks, while Raphael would sing, and others, also connected by video, could join in vocally or on the piano. With the help of a Zoom application, they can have several cameras switched on and off for several participants at any one time. They also introduce third parties into the process; for example, one student, Vanik, sang for a professional musician, who then gave him feedback in the form of coaching and evaluation. Music is just one of many activities engaging the students at My Way. The center’s trained psychologists help the youngsters develop their capacity for logical thinking, they learn to recognize musical works or instruments, and also develop skills in more academic areas, like math and geography. While in the center, they would work together to make various objects, like toys, ceramics, decorative candles and souvenirs; now, at home, they are following the instruction of ergo therapists, doing it all by video. And, to help them cope with the new circumstances created by the pandemic crisis, instructors tell the children social stories that illustrate public health measures, for example, about staying home to avoid infection, washing hands, etc.

Decorative candles for April 24th

Artistic activity plays a very important role at My Way, not only in the ceramics and souvenirs that the pupils make, but in drawing and painting. Again, to cope with the new circumstances, videos make it possible for the youngsters to present their works to their friends. And in a cooperative effort with the National Gallery, the students are able to access works from their collection to copy, and then exhibit.

Until the center can open again and return to normal functioning, staff and students focus on maintaining close contact through visual means. A youngster out for a bike ride will receive the assignment to take photos and send them around. Even practical tasks, like cooking (with the help of recipes and video demonstrations by the teachers) or washing the dishes, can be shared by video, and generate excitement and encouragement from the others.

The board members and specialists in the staff have organized some time in their new schedule to conduct seminars, both internal and external. Some of these deal with professional issues, others are designed for the parents, to help them deal with the special challenges of the situation, suggesting ideas for activities, to keep the students’ spirits and motivation high. “Anything that keeps people happy!” says Sona Petrosyan. One positive by-product of the online learning program is that former students from abroad, who have returned to their homes in Europe of the USA, have been able to participate again with the center and its staff. Those living in Yerevan are looking forward to returning to the classrooms, to spend time in person. “We have accumulated birthdays to celebrate,” Petrosyan reports, “have selected places to visit within our socialization projects, and cannot wait to return.” She called it an “amazing phenomenon … if treated the right way and with love, people with autism need and love their warm environment not less, but more than ‘neuro-typical’ people! This is our victory and we cannot wait for the situation to return to normal, to be again with people we love, doing things we love, interact and socialize.”