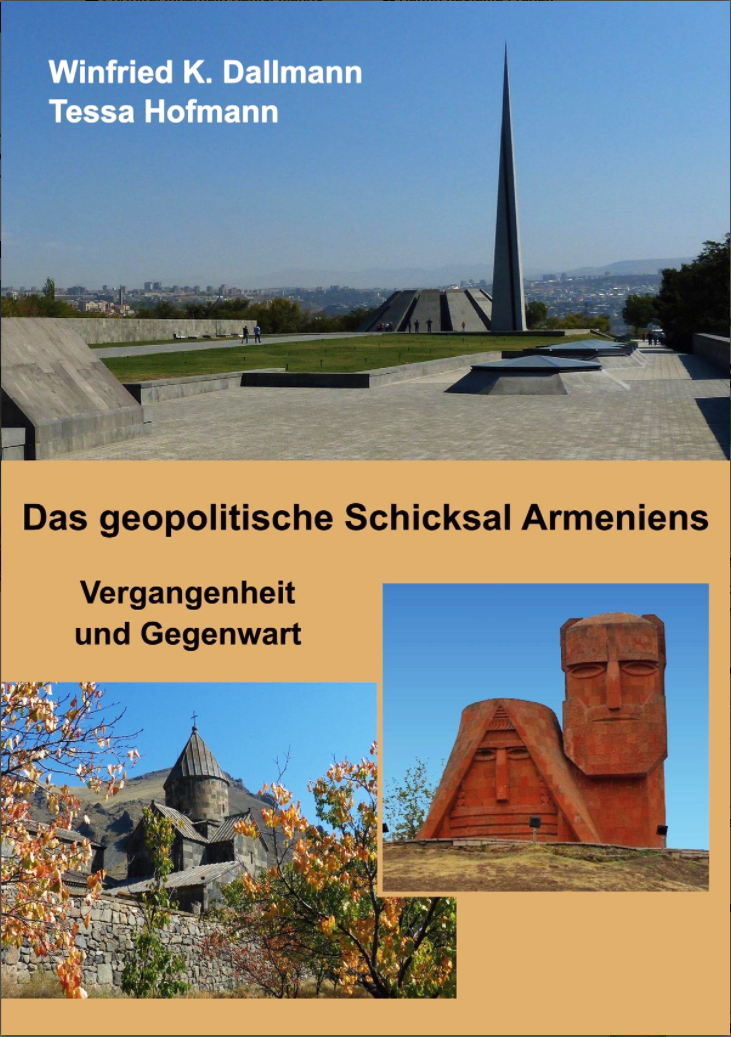

Das neueste Buch der Autorin

Ein General zwischen Staatsräson und Moral: Otto Liman von Sanders

und der Völkermord an den Armeniern

BuchvorstellungBerlin Human Rights Organization Calls for Artsakh Airlift

Although overlooked by the mass media, there have been important initiatives taken in Germany to protest Azerbaijan’s continuing aggression and blockade. Not only have demonstrations taken place regularly in front of the Azerbaijan Embassy in Berlin, but an increasing number of individuals and organizations, human rights proponents as well as religious figures, are coming together to demand action on the part of the German government to protect the Armenian people and sanction Azerbaijan for its continuing aggression.

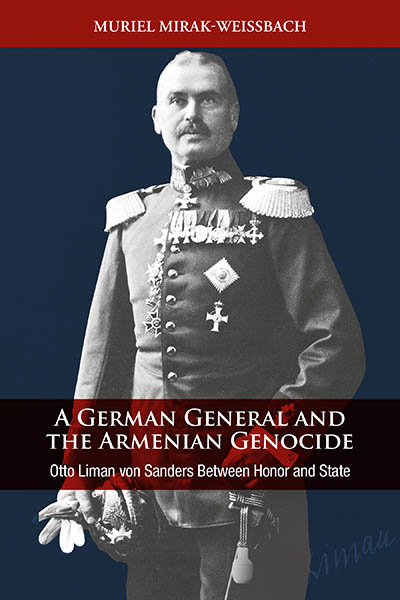

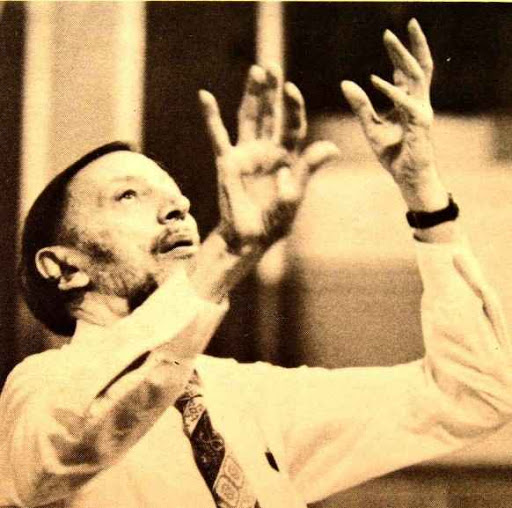

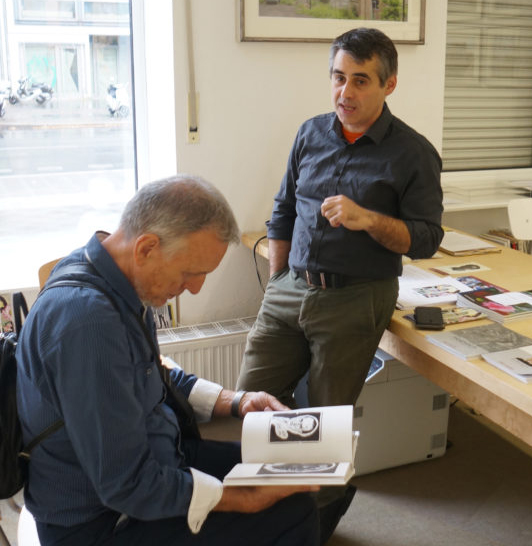

Author Muriel Mirak-Weissbach Speaks about New Book at Cultural Foundation

ARLINGTON, Mass. — About 100 people attended on September 28 the program, co-sponsored by the Tekeyan Cultural Organization, the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research, Berghahn Publishing and the Goethe-Institut Boston.

Plea to Stop Genocide Falls on Deaf Ears in ‘Homo Politicus’

The film, “Homo Politicus,” which is Latin for political man or activist, was presented on January 23 and 24, at the Lepsiushaus in Potsdam and the AKEBI civil society group office, respectively. In addition to hosts and moderators Ulrich Rosenau and Öndercan Muti, filmmaker and director Hacı Orman and genocide scholar Tessa Hofmann provided historical background to the film and the parameters of legal and institutional initiatives developed since World War II.

Art and Artists through the Generations

Is artistic talent hereditary or is it learned? In families with several great musicians, like the Bach or the Strauss families, and in the visual arts, as in the cases of Italian Renaissance painters like Fra Filippo Lippi and son Filippino or Dutch and Flemish masters Pieter Bruegel the Elder and sons Peter and Jan, creativity seems to have passed from father to son.

Armenian Symphony Tours Germany

Music lovers in Wiesbaden greeted the Armenian State Symphony Orchestra with enthusiastic applause on November 27, when the renowned ensemble performed the tenth in a series of 15 concerts, on a whirlwind tour through the Federal Republic. Under the baton of conductor Sergey Smbatyan, the orchestra performed a short piece by Alexander Artunian, followed by two works by Pyotr Tchaikovsky for piano and orchestra, with virtuoso Olga Scheps at the keyboard.

One Meme Away from War

How can the reality of war and genocide be effectively expressed? Can human language provide us the means to “say the unspeakable”? A question debated among genocide researchers, this was an issue that arose during a round table hosted by the Armenian delegation at the recent Frankfurt Book Fair.

Tessa Hofmann Receives the German Federal Cross of Merit

It could have been an ecumenical conference of Eastern Christians: there were Greek Orthodox, Armenian Apostolic and Orthodox, Syriac Aramaic; but there were also Turks, Kurds and Alevites, as well as many, many Germans. They had all gathered in Berlin-Friedenau on October 20 to celebrate together the festive bestowal of the German Federal Cross of Merit on Tessa Hofmann Savvidis. Their presence symbolized at once the diversity — and the unity — of religious, ethnic and political communities with whom Hofmann has collaborated and for whose human rights she has fought.

Komitas Duo Wins European Honors

At the 10th European Chamber Music Competition Karlsruhe, held on September 24-26 in the German city of that name, pianist Hasmik Sarukian and cellist Egon Buchner — the Komitas Duo — earned second prize. The competition for up-and-coming young musicians, which has been held semi-annually (with two exceptions) since 2005, is organized by the city of Karlsruhe and the Max Reger Institute located there.

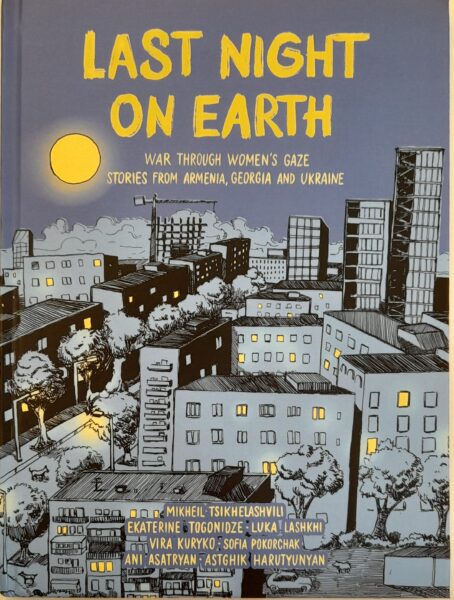

New Book Portrays How Women Experience War

Armenia was present again this year at the Frankfurt Book Fair (FBF), the most important such exhibition worldwide, with a new, expanded display. The enlarged stand provided ample space to showcase new titles, in Armenian as well as foreign language translations. And on Friday, October 17, the third day of the five-day fair and the first open to the public, Armenia presented a new book to visitors.

Genocide Scholar Tessa Hofmann Honored in Germany

German Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier signed an order on June 13 naming Dr. Tessa Hofmann, sociology scholar, genocide researcher, and human rights proponent, as recipient of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. In his letter informing Hofmann two weeks later of the honor, George Klussmann, the Berlin Mayor’s chief of protocol, wrote, “With your exceptional personal achievements you have made an outstanding contribution to the common good of the Federal Republic of Germany. For this engagement, I render my thanks.”

Armenians Join Intercultural Festival

In Germany, as in the rest of Europe, social tensions concerning newcomers from foreign countries have grown with the rising tide of immigration; stories of conflict and violence too often overshadow the message of successful integration. So, it is a pleasure to report on events that celebrate successful intercultural exchange.

Gyumri Musicians Tour Germany, Austria

Gyumri is known informally as the cultural capital of Armenia and for good reason. In addition to its traditional excellence in the visual arts, it hosts several outstanding music schools as well as a Conservatory, the Gyumri branch of the Komitas State Conservatory in Yerevan.

Armenian Artists in the Spotlight in Germany

Artist and gallerist Archi Galentz’s project space, InteriorDAsein, is presenting an exhibition titled “Aspects of Armenian painting. From Ivan Aivazovsky to Narine Zolyan,” as part of projects that not only represent visual culture but also invite discussion about the prospects for the existence and development of a distinctive culture.

Dr. Robert Mirak, Scholar, Author, Family man, and Entrepreneur, Passes

Robert Mirak passed away peacefully at home surrounded by his loved ones on July 17 at the age of 92.

Bob was born in 1933, the first son of Artemis and John Mirak, both orphans who had survived the Armenian genocide and started a new life in America.

Debating Trump’s ‘Peacemaking’ in Germany

News of the deal that Donald Trump believes might win him the Nobel Peace Prize did not make front-page headlines in Germany. What sparse coverage appeared was light on content, and less than enthusiastic in tone. The general line was: a deal has been made, but there is a long way to go.

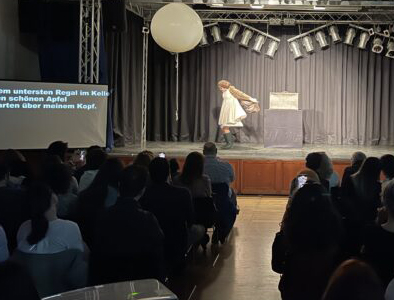

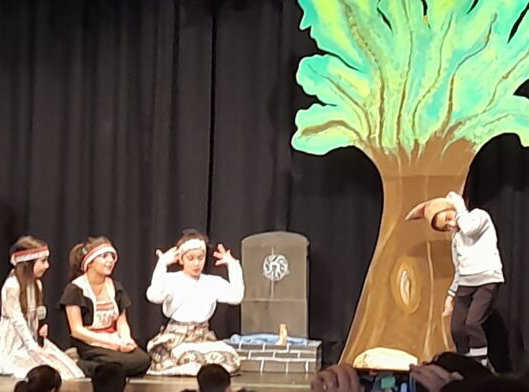

“The Play’s the Thing…”: Theater Is Therapy for Armenian Children

Michael Sahakyan is one of a growing number of Armenian children who take part acting in the Miasin (“Together”) Drama Group of the Center for Children with Learning Disabilities.

This inclusive theater group is a project founded in March 2022 under the direction of Marine Asatryan, who has extensive experience using the tools of the theater to help children with special needs and to enhance inclusiveness.

Naumburg and Armavir Become Twin Cities

Two years after Gyumri and Halle consolidated their twin-city relationship, now another two cities have established ties symbolizing a growing relationship between Armenia and Germany on the local level. Armavir and Naumburg celebrated the official signing ceremony in the city located in Germany’s federal state of Saxon-Anhalt on June 13.

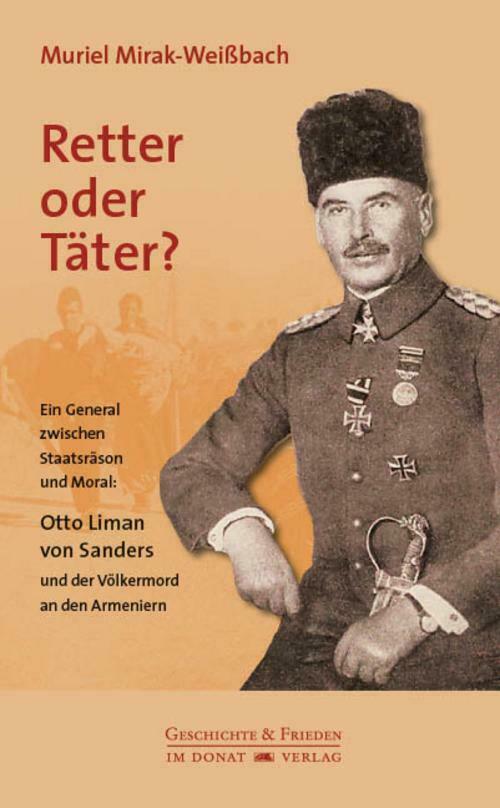

Muriel Mirak-Weissbach Writes New Book on General Otto Liman von Sanders

Berghahn books will release a new book this summer by veteran Armenian Mirror-Spectator correspondent and historian Muriel Mirak-Weissbach. The book, titled A German General and the Armenian Genocide: Otto Liman von Sanders Between Honor and State, will be released in July.

Events in Germany Honor Genocide Victims

Every April Germans join with Armenians to commemorate the victims of the 1915 Armenian Genocide, with prominent events in Berlin and Frankfurt organized by the Central Council of the Armenians in Germany (ZAD) and the Diocese of the Armenian Church in Germany.

This year, the 110th anniversary, several other cities hosted events, from Stuttgart to Bremen, Hamburg to Cologne and Munich. Jonathan Spangenberg, chairman of the board of the ZAD, opened the gatherings both in Berlin and Frankfurt, and Bishop Serovpé Isakhanyan, Primate of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Germany, offered concluding remarks and requiem prayers.

‘Barber of Seville’ Brings Down the House in Wiesbaden

On March 30, the Wiesbaden State Theater premiered a fantastic production of Giacomo Rossini’s comic opera, “The Barber of Seville,” with bass-baritone Hovhannes Karapetyan in the role of Dottor Bartolo.

Silvina Der Meguerditchian: An Artist Who Cares

There is no mystery behind the fact that Armenian art, especially in the diaspora, bears the imprint of the genocide: directly, as in representational figurative art or literature; obliquely, as in musical reflections; or symbolically, as in abstract conceptual impressions.

An exhibition that has just opened in Berlin features the works of an artist who explores all three modes of expression, in depth and beauty. Silvina Der Meguerditchian.

Protest in Berlin Calls for Immediate Action Against Azerbaijan’s Unlawful Detentions

Speakers at the protest condemned European inaction, with Spangenberg referencing Germany’s historical responsibility to prevent genocide and protect vulnerable communities. He criticized Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s failure to take decisive action and called for a formal petition to the International Criminal Court against Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev.

Berlin Exhibition Opens Eyes through Myths

Art is a language, like poetry, but is visual. It speaks through metaphors and allegories, communicating across verbal language barriers, through images, figurative or abstract. An exhibition has opened in Berlin in which the artistic language of communication is mythology. Entitled, “Mythical Images – On the Relevance of a Refuge,” it opened on March 28 and will run until April 20, at InteriorDAsein, an atelier and meeting place for artists founded by Archi Galentz.

Musicians Delight International, Local Audience in Wiesbaden Concert to Benefit Mirak-Weissbach Foundation

A benefit concert took place in Wiesbaden on Sunday, January 12, to raise funds for projects supporting Armenian refugees from Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh). The venue was the Anglican Church of St. Augustine of Canterbury in Hessen’s state capital. More than a benefit concert, it turned out to be an intercultural gathering, bringing together members of different ethnic and religious backgrounds, who shared the beauty of music from Armenia, Europe, and America.

Human Rights Activists in Germany Call for International Observers in Baku Trial of Armenian POWs

On January 17, the trials of 23 people illegally arrested by Azerbaijan as a result of the attack on Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) in September 2023 began in Baku. Several German human rights organizations have warned of a politically motivated show trial and are calling for observation by German embassy staff.

Baku Massacre 35 Years Later: Remembrance and Denial

Except for April 24, recognized internationally as the anniversary of the beginning of the Ottoman genocide, it is not common practice for major German media to observe Armenian commemorations. Recently, that changed. On the 35th anniversary of the Baku massacres, the leading public broadcasting radio station featured it on its “Calendar page” spot on January 12.

Artists Bring International Repertoire, Humor to Frankfurt Performance

“Opera plus” was the title of the concert held on November 30 at the International Theater of Frankfurt, a venue known for its artistic excellence and cultural diversity. Although its origins stretch back to 1987, the ITF in its current form as a guest performance stage represents a collaborative effort established in 1998 between the Cultural Department of Frankfurt and the sponsoring association (Förderverein) of the theater.

Wiesbaden State Theater Welcomes Armenian Vocalist

It was not simply a wonderful concert, but a rare and delightful musical encounter. The Wiesbaden Staatstheater opened its sumptuous foyer on November 11 to a Lieder-Soiree (evening song recital), where guests, served with a glass of wine, took their places at small tables in an atmosphere that evoked images of intimate gatherings of music lovers at the beginning of the 20th century.

Poetry in Word and Image: Anahit Hayrapetyan in Frankfurt

The annual Frankfurt Book Fair represents a cultural highpoint in Germany, as authors, publishers, booksellers, literary agents, and booklovers from around the world gather to honor one country’s literary contributions, and explore the vast offering of new titles in every language culture. This year’s guest country was Italy, which presented its new selections under the rubric “Roots in the Future.”

As always, the Republic of Armenia is present...

History Is Not Capricious: Exploring Root Causes

Das geopolitische Schicksal Armeniens:Vergangenheit und Gegenwart (Armenian’s Geopolitical Fate: Past and Present). The book is the result of a collaborative effort by Norwegian geologist and ethnologist Winfried K. Dallmann and German sociologist, genocide researcher and human rights proponent Tessa Hofmann.

Armenian Community Promotes Unity In Diversity

On September 7, the Armenian Cultural Association (AKV) in Hesse proudly celebrated its 55th jubilee, one of the oldest immigrant communities in the state. While presenting various facets of the uniqueness of Armenian culture, the festive gathering focused on the integrative function of cultural exchange. The event was entitled, “55 Years of Culture, Integration, and Language Diversity.”

Civil Society Groups in Germany Raise Their Voices against Azerbaijan Hosting COP29

Although there are five months to go before the scheduled opening of the UN climate summit COP29 in Baku, November 11 to 22, human rights groups in Germany have been mobilizing to demand that the Berlin government act to release political prisoners held in the Azerbaijani capital.

Armenian Musician to Compete in Eurovision Contest

If you mention “Eurovision” in Germany, or any other European country, what comes to mind for most people is the Eurovision Song Contest for popular music. This year’s event took place in May, with Swiss musician Nemo winning.

Not everyone knows that there is also a Eurovision contest held for classical artists, which this year will take place in Norway on August 17.

And a musician from the Republic of Armenia will be among the contestants.

Revisiting Gyumri, Armenia’s Cultural Capital

It was our long-awaited trip to Armenia, the first since 2019. The Coronavirus pandemic, then repeated, escalating conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh), culminating in the mass expulsion of Armenians in September 2023, had interrupted our happy routine of yearly trips to Yerevan.

In April this year we finally returned for a week-long visit to the capital, several villages nearby, as well as the cultural capital Gyumri.

Call for Help Restores Music for Artsakh Children and a Dedicated Music Teacher Twice a Refugee

Garen Garibyan does not give up. Although he has been forced to leave Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) twice, his opera studio project for children will continue to grow and thrive. His story is a demonstration of courage, and an inspiration.

Armenians Commemorate Genocide Anniversary with Moreno Ocampo in Germany as Aliyev Visits

Every year on April 24, Armenians and Germans gather in the historic St. Paul’s Church in Frankfurt and the French Cathedral in Berlin to pay homage to those who perished. Representatives of the government, the Armenian ambassador and other diplomats, local political leaders, and leaders of the religious communities speak, and a special guest holds a keynote address.

Germany Hosts Armenian-Azerbaijan Talks – And Then?

On February 28-29, German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock met with her counterparts from Armenia and Azerbaijan, Ararat Mirzoyan and Jeyhun Bayramov, respectively.

The two-day discussions held in the foreign ministry’s guest house, Villa Borsig, in Berlin were characterized in official releases as “negotiations” centered on perspectives of the draft bilateral Agreement on Establishment of Peace and Interstate Relations between the two nations.

Zvartnots Launches New IT Center for Youngsters

On February 3, over 65 people gathered in Zvartnots, Vagharshapat for the festive inauguration of a new IT center for youngsters. Presiding over the ceremonies were Lilia Totalyan, who is president of the Social Support Computer Center NGO in Echmiadzin and...

Creative Challenges for Aspiring Young Artists

What better way to honor a great artist than to foster development of art in youngsters? That is the idea behind the International Art Festival and Competition hosted by the Armenian Cultural Society in Hessen (Armenische Kulturverein in Hessen AKV) at the end of 2023.

Children Show the Therapeutic Power of Drama

In recent years, numerous governments and public institutions have devoted increasing attention to promoting harmony among diversity in society. While political bodies may have established legal guidelines for integrating persons of different backgrounds, cultures and personal capabilities, creative approaches by therapists in the cultural realm have developed exciting results in theater. Drama therapy has proven to be an effective means for individuals to interact on a metaphorical level, to play roles in fictional narratives that allow them to deal with difficultie, swhether real disabilities or emotional, psychological barriers to healthy social interchange.

Genocide Monument Still Stands in Cologne

As the fireworks rang in the New Year 2024, few people thought there was much to celebrate anywhere in the world. But in the German city of Cologne, there was indeed: the memorial stele that honors the victims of the Ottoman genocide against the Armenians was not going to disappear, as had been planned by the city authorities, but would stay put in its place along the Rhine river, not far from a statue of Germany’s last emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Artsakh Refugees Find New Home at Camp

Humanitarian aid continues to flow from generous German organizations into Armenia, to help alleviate the suffering of those among the 100,000 people forced to flee their homes in Artsakh. Among them is the Berlin-based human rights organization, Against Genocide, for International Understanding (AGA), which raised $28,000 to support a vital initiative launched by the church.

Analysis: Artsakh’s Water and Baku’s Thirst

In the lead up to and then after the remarkable acts of aggression by Azerbaijan which led to the forced expulsion of Armenians from Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh), analyses by various experts, politicians and scholars have focused on the ethnic, religious and geopolitical causes. A long history of conflict documents all three aspects, and during the 2020 war, the racist character of Baku’s military campaign was blatant.

Armenian Genocide Monument: Remembrance or Denial?

“This pain affects all of us.” So reads the text borne by a monument in the German city of Cologne along the Rhine River. It refers to the genocide perpetrated by the Young Turk regime during World War I against the Armenian population. But the words take on further meaning in light of the fact that, after a long political battle for and against the monument, a decision has been made to remove it.

Humanitarian Aid from Germany Raised for Displaced Armenians of Artsakh

In response to the humanitarian catastrophe created by Azerbaijan’s forced expulsion of over 100,000 Armenians from Artsakh, Armenians in Germany have been working with German organizations to supply urgent relief. In the forefront of efforts has been the Armenian Embassy in Berlin, working with Armenian-German groups and church communities.

No More ‘Enver Pasha Bridge’ in Potsdam after Complaint

Germany is known for its culture of remembrance, manifest in official acknowledgement of heinous crimes committed by previous governments in history, from the massacre of the Herero and Nama in 1904-1908 in Namibia, to complicity in the Ottoman genocide against the Armenians and other Christian minorities, to the Holocaust.

Erdogan Greeted by Demos in Berlin

Reportedly 2,800 police were deployed in Berlin on Friday, November 25, to protect Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who was making a short visit. Members of the Society for Threatened Peoples (GfbV) and the Syrian Kurdish Diaspora Network gathered in front of the residence of German President Frank-Walter Steinmeyer, who welcomed the guest. The GfbV’s banner read: “No Red Carpet for Islamist Erdogan!”

Armenians in Frankfurt Assert the Power of Literature

Despite crises at home and abroad, several representatives of Armenia’s rich literary culture and publishing enterprises travelled to Frankfurt for this year’s book fair, which took place from October 18 to 27. Receiving visitors at the large Armenian stand were Arevik Ashkharoyan, founder of ARI Literary and Talent Agency, Zara Hakobyan, from the National Library of Armenia, and Ani Musheghyan, researcher and librarian from the Komitas Museum-Institute. And featured in the Armenian presence were two authors, both women: Lusine Kharatyan and Susanna Harutyunyan.

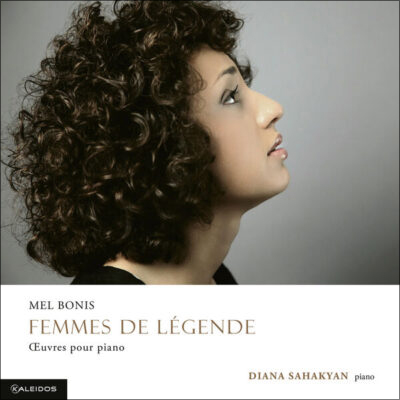

Diana Sahakyan Honors Women Composers

Armenia is famous for its musical culture, and the excellence of musical education. As my husband and I learned during our first visit there several years ago, the teaching staff of the numerous schools and conservatories pride themselves on training world-class musicians. It is almost proverbial to note that in the best orchestras, operas, and music academies anywhere, you can usually find an Armenian.

Frankfurt Demonstration Supports Artsakh

Three days after Azerbaijan’s military aggression, which led to the expulsion of the Armenians of Nagorno Karabakh, demonstrations took place not only in Berlin and Frankfurt. Organized by the Armenian Cultural Association in Hessen (AKV).

Germans, Armenians to Olaf Scholz: Stop Genocide!

The demonstration in Berlin on September 23 had been organized weeks earlier; the Diocese of the Armenian Church in Germany, the Central Council of Armenians in Germany, along with two leading human rights groups, the Society for Threatened Peoples (GfbV) and Against Genocide, for International Understanding (AGA), had joined forces to awaken German public opinion to the impending genocide against Artsakh Armenians under Azerbaijan’s blockade.

Paris Gala for Artsakh: ‘One Nation, One Culture, One Child, One Hope’

“Wars may come to an end, but traumas last for a long time thereafter. All wars present the same forms of horror, and they leave survivors with weighty handicaps, both visible and invisible.” These are the words of Eugénie Alecian, a leading French-Armenian musician and composer.

Armenians in Germany Hold Rallies in Support of Artsakh

On September 2, Armenians in Berlin, Hamburg and Frankfurt were joined by local human rights groups in demonstrations to protest the threatened genocide in Karabakh (Artsakh), and demand effective humanitarian and political intervention.

German Press Sounds Alarm on Threat of Genocide

It was two hundred years ago that Edmund Burke coined the term, the Fourth Estate, but the point he made is as relevant today as then. The reference is to the press, which the British philosopher and politician catalogued as a major power in public affairs, after the three “estates” of the clergy, the nobility and the commoners or bourgeoisie.

German Government Quiet as Genocide Looms in Artsakh

A century ago, when the Young Turk regime committed genocide against the Armenians and other Christian minorities, Germany, its wartime ally, could have intervened, but did not. Single individuals, like Johannes Lepsius, Consul Walter Rössler, and General Liman von Sanders, to name a few, did what they could to protect the targeted groups.

Tessa Hofmann: The Situation in Artsakh Corresponds to UN Genocide Convention

Tessa Hofmann, a well-known German scholar of Armenian and Genocide studies, PhD, research scholar at the Free University of Berlin, on April 11 gave an interview to the Orbeli Analytical Research Center about the severe humanitarian situation in Artsakh caused by the blockade of the Lachin Corridor, the ultimate goal of the genocidal policy of the Azerbaijani authorities, and about the possibilities of settlement of the problem within the framework of international law.

Arman Hambardzumyan Opens Unique Atelier

About 10 kilometers from the center of Yerevan in a village called Zovuni a new cultural initiative has come into being, which merits the attention of artists and art lovers. It is the home and studio of Arman Hambardzumyan and his wife, Lusine Sargsian, designed and built by the artist himself. Not only is it a residence and atelier, but also an active cultural center which will host exhibitions, discussions about art, and other activities.

Memory Culture Under Attack in Cologne

Since 2018, the city of Cologne in the Ruhr region of Germany has been the site of a tug-of-war between the Armenian community, consisting of about 6,000 people, and a vast coalition of about 50 Turkish associations.

The bone of contention is a 1.5-meter-high stele, a monument to the memory of the victims of the Armenian Genocide.

Gyumri Conservatory Hosts Premier Harp Concert

On June 18, 2023, a historic concert took place in the Gyumri branch of the Komitas State Conservatory of Yerevan. It was the first time in the Conservatory’s 25-year history that it had showcased a harp concert. The solo concert featured Hasmik Mkrtchyan, a second-year student in the string department. The talented harpist, who studies under Prof. Gayane Harutyunyan, performed in the small hall of the Conservatory.

Little Singers of Armenia Celebrate Bach Jubilee and Their Own

The festival “Bach for Future” took place in Leipzig, from June 8 to 18, with 160 events featuring musicians from around the world, and drawing a record crowd of 70,000 guests. Among the celebrated performers were the Little Singers of Armenia. They offered three concerts. They performed works by Armenian composers R. Petrosyan and Komitas, as well as classical German artists.

One ‘Small Step’ for Young Musicians in Yerevan

The name of the competition may be “Small Step,” but the voices of the singers were big and beautiful. This year the event, which has previously brought together participants from Armenia and Artsakh, is to be international, with contestants invited from the Islamic Republic of Iran, Georgia and the Russian Federation.

Artists from Countries at War Exhibit Together

A group of women from Ukraine, Belarus and Russia have defied the undeclared war on culture, to appear together and present their works.

The venue is the Gallery Wolf & Galentz in Berlin, which was established in 2019 by Armenian artist Archi Galentz and gallerist Andreas Wolf. The current show, titled “Heartbeat, a joint exhibition” held a vernissage on June 2 and runs until August 16.

All Victims of Genocide Perpetrated by Young Turks Honored at Germany Event

During World War I it was not only the Armenians who fell victim to genocide under the Young Turk regime; other Christians, Greeks and Syrian Orthodox, Aramaeans, were targeted as well, deported, and massacred. On the weekend of May 19-21, in Berlin and Munich, members of these communities joined to pay tribute to the Pontic Greek victims of the Ottoman genocide.

Artsakh’s Drama Comes to Germany

On April 22, the reality of the humanitarian crisis in Nagorno-Karabakh occupied center stage in a theater in Wiesbaden, the capital of the German federal state Hessen. A capacity crowd of 80 theater goers, mainly from the local German-Armenian community, attended a performance of the monodrama, “My Family in My Suitcase,” which portrays the plight of a family in the contested region.

German Armenians Commemorate Armenia’s Past Tragedy in a Perilous Present

It was in the historic Paulskirche (Church of St. Paul) in Frankfurt that the first National Assembly met in 1848 and worked to produce the first constitution for a German republic. This year again it hosted the International Day of Commemoration of the Armenian Genocide on Sunday, April 23.

Gyumri and Halle Become Twin Cities

To judge by the number of visits to Berlin by Armenian political leaders, relations between Germany and Armenia are entering a new phase.

A ceremony on March 6,2023 in which Gyumri and Halle (Saale) officially sealed their status as sister cities. The festive event took place simultaneously in both cities.

Painter Soghomonyan Repatriates from Germany and Exhibits in Yerevan

When artists Van Soghomonyan and Nona Gabrielyan moved back to Yerevan in 2022 after thirty years’ activity in Wiesbaden, Germany, some may have thought they were going to retire. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Giving Nagorno-Karabakh a Voice Through Poetry

The tug-of-war continues over Azerbaijan’s blockade of the Lachin Corridor, in the wake of demands by the International Court of Justice that it be lifted and the deployment of a European Union mission to the area. Azerbaijan, to date, has not budged. In addition to mobilizing political protests and organizing humanitarian support, what can Armenians in the diaspora do?

The answer offered by Agapi Mkrtchian is, “give the Nagorno Karabakh Armenians a voice.”

Armenian Carnival in Wiesbaden

After two years of pandemic restrictions, Germans were able to resume Carnival celebrations again this February. Carnival here is an age-old tradition, especially in the Catholic areas of Bavaria and the Rhineland. Large crowds gather in bright costumes and high spirits for festive sessions characterized by political cabaret and music. As the season comes to a close just before the beginning of Lent, cities like Cologne and Mainz host festive parades, again featuring huge, politically satirical floats, marching bands and costumed jesters.

FM Mirzoyan Rallies German, European Support

If the growing crisis in Nagorno-Karabakh has finally landed on the political agenda in Berlin, it has a lot to do with the working visit of Armenian Foreign Minister Ararat Mirzoyan to the German capital last week.

In two packed days, he met with the people and institutions that could make a significant contribution.

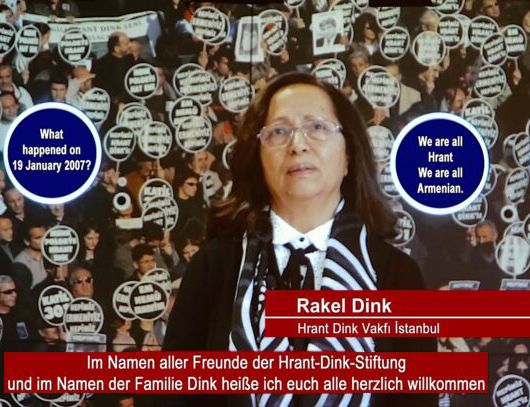

The Challenge of Hrant Dink’s Legacy

A decade and a half after the assassination of Hrant Dink, Xenophobic hatred and violence are being fomented by right-wing extremists, targeting newcomers, whether immigrants or refugees.

This was the subject of a discussion on January 21, moderated by Raffi Kantian, chairman of the German-Armenian Society (DAG), in the course of a meeting in Cologne, commemorating the anniversary of the death of Dink.

Nagorno-Karabakh Blockade: Can (and Will) Europe Act?

In the wake of growing protest actions by human rights groups in several European countries, public awareness of the dimensions and dangers inherent in the Nagorno-Karabakh crisis has been increasing. Major press organs and prominent think tanks are expanding discussion of the dramatic humanitarian crisis caused by the continuing blockade of the Lachin corridor. One webinar on January 18 sponsored by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, affiliated with the Green Party, attracted 300 participants.

Germans, Armenians Put the Nagorno-Karabakh Blockade on the Political Agenda

For weeks, political forces in Germany have turned a blind eye to the ongoing Artsakh crisis, while mainstream press organs have observed a complicit silence. Now, as the humanitarian crisis created by Azerbaijan’s blockade of the Lachin corridor worsens, public opinion in Germany and Europe is slowly waking up.

Berlin Human Rights Organization Calls for Artsakh Airlift

Although overlooked by the mass media, there have been important initiatives taken in Germany to protest Azerbaijan’s continuing aggression and blockade. Not only have demonstrations taken place regularly in front of the Azerbaijan Embassy in Berlin, but an increasing number of individuals and organizations, human rights proponents as well as religious figures, are coming together to demand action on the part of the German government to protect the Armenian people and sanction Azerbaijan for its continuing aggression.

Tessa Hofmann, chairwoman of the board of the Berlin-based human rights organization, Against Genocide, for International Understanding (AGA), has recently issued a call for an airlift, to provide the people of blockaded Artsakh vital humanitarian relief.

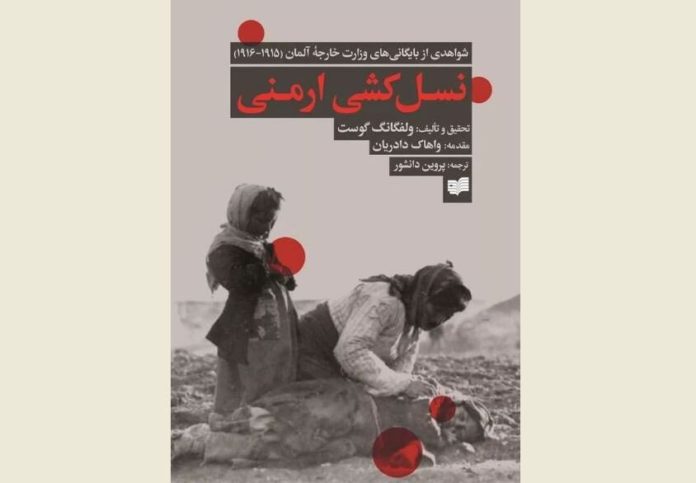

Armenian Genocide Books by Gust, Kévorkian Translated into Farsi

Two seminal studies of the Armenian genocide have recently appeared in Iran, in Farsi (Persian) translations. The first is Wolfgang Gust’s monumental collection of documents from the German Foreign Ministry archives, which detail what Imperial Germany knew or did not know, did or did not do, while the Young Turk regime leadership of its wartime Ottoman allies was carrying out the Genocide against the Armenians and other Christian minorities. Gust’s book, first published in German in 2005, was released in English by Berghahn in 2014, titled,

The Armenian Genocide in the Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Germany in 1915-16.

New Armenia Ambassador to Berlin in Dialogue on War and Peace

On November 26 the French Senate voted 295-1 in favor of a resolution calling for sanctions on Azerbaijan in response to its attacks against Armenia and aggression against Nagorno-Karabakh. It demanded Baku pull its troops out of Armenia, and reaffirmed a resolution the Senate had passed in 2020 in favor of French government recognition of Nagorno-Karabakh.

The immediate question posed by the French move is: how will the rest of Europe respond? First and foremost, how will Germany respond?

Genocide and Denial: The Human Dimension

Scholars and human rights proponents who came together earlier this month for a conference on “Genocide and Denial,” were continuing a discussion process begun in January this year. As Lepsiushaus director Dr. Roy Knocke recalled, the first conference, addressed by Prof. Taner Akçam and German Holocaust historian Wolfgang Benz, dealt with the denial of the Shoah and the Armenian Genocide as viewed from the historical perspective, whereas the second session would “develop the theme further, from a philosophical, sociopsychological and juridical perspective, with reference to human rights practice.”

Multifaceted Debate on Genocide Denial in Germany

Denial has been identified as the last stage of every genocide. Why, despite the testimony provided by ample documentation, are these crimes against humanity so stubbornly disputed? What are the reasons for such a defensive posture? What forms does denial assume? And how can this defensive posture be overcome?

These are the questions posed by the organizers and treated by a group of experts at the historic Lepsiushaus in Potsdam, near Berlin, during an interdisciplinary conference on November 5, entitled, “Genocide and Denial.”

ArmeniaHonors Charents in Frankfurt

The Frankfurt Book Fair, the largest and most important worldwide, is something I look forward to every October. This year, after two years of limitations imposed by the Covid pandemic, the fair opened as an in-person event, and people came in droves. Though the numbers still do not reach those of pre-pandemic years, there were a good 4,000 exhibitors from 95 countries and 180,000 visitors. In the first two days, reserved for trade visitors, there were 93,000 in attendance, and from Friday to Sunday, that figure was augmented by another 87,000 private visitors.

Dr. Kantian Is Trying to Correct a Historic Misattribution

Loss of life is the greatest cost of war, and in the continuing Azerbaijani aggression against Artsakh and the Republic of Armenia, casualties have been high. Along with destroying human lives, expelling Armenians and devastating their property, Azerbaijan has pursued a campaign to erase evidence of the physical and cultural existence of the Armenian people in the region. This includes destroying cultural and religious monuments, turning churches into mosques, and changing place names.

Berlin Program Marks Centennial of Burning of Smyrna

“The Smyrna horror is beyond the conception of the imagination and the power of words.” This is how an American physician, Dr. Esther Clayson Pohl Lovejoy (1869-1967), characterized the events she witnessed in the city of Smyrna in September 1922.

In the German capital, diplomats, political figures, representatives of the Greek and Armenian communities, civil society and clergy, as well as citizens gathered to commemorate the victims of The Great Fire of Smyrna.

Volunteers Help Build Armenia’s Future

Justin Leach and his cousin Christina Kew were two of a group of eight youngsters from America who took part in the Paros Foundation’s SERVICE Armenia program, spending three weeks, from July 3-24, in the country that their ancestor, survivors of the Genocide, never had the opportunity to visit.

Their great-grandparents, Artemis and John Mirak, would have been thrilled to learn of their experience. Their great-aunt (who is writing these lines) certainly was excited to talk to them about it.

Virtual Genocide Memorial Launched

On August 10, after three years of hard work, Dr. Tessa Hofmann announced the launch of a new website, The Virtual Genocide Memorial.

Hofmann is a pioneer of genocide research in Germany, one of the first scholars here to publish scientific research on the Armenian genocide.

Active for many years at the Free University of Berlin, she has produced scores of books and articles on the fate of the Christian communities in the Ottoman Empire, not only the Armenians, but also the Greeks and Syrian Orthodox (Aramaeans).

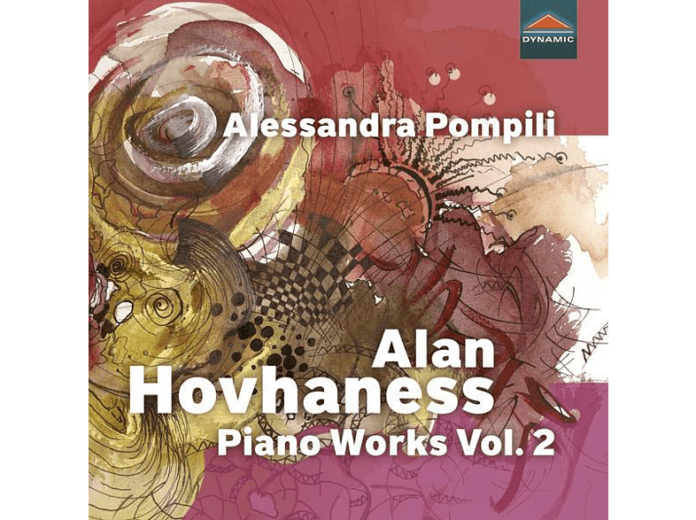

Alessandra Pompili Is on Astral Journey with Alan Hovhaness

“My purpose is to create music not for snobs but for all people, music which is beautiful and healing.” These words of composer Alan Hovhaness appear in a short presentation of a recently released CD. It is the second recording that pianist Alessandra Pompili has produced of his piano works and it is clear that she shares the composer’s approach to music.

Preserving the Art of the Written Word

When Mesrob Mashtots arrived in Echmiadzin with his alphabet, he was happier (in the words of his biographer Koriwn) than was Moses descending with the holy tablets from Mount Sinai. Truly, his invention of the Armenian alphabet in 405 A.D. marked the beginning of a new era for the nation and the people.

Artists Share

the Joy of Music in Marburg

What better way to enter summer in this troubled year than with a musical tribute to friendship across national borders? On June 17, a group of musicians gathered in the St. Marien Lutheran parish in historic Marburg, to present a selection of well-known pieces from many different cultures. The artists, mostly Armenian, performed works for voice, piano and string instruments to a large and very appreciative audience.

Dresden Hosts Photo Exhibition on Genocide

A picture is worth a thousand words. The saying has become a cliché, and for good reason: it holds true. Nothing could prove this more convincingly than an exhibition that opened on June 16 in Dresden, Germany. Organized by the “Haytun” Armenian Cultural Association in Dresden together with the Armenian Information and Documentation Center (IZDA, Berlin), the vernissage took place in the Martin Luther Church.

Honoring Women’s Achievements in Gyumri

On May 7, an exhibition opened in Gyumri, entitled “World of Women,” honoring their efforts in paintings by Armenian visual artist Lilit Bachach and works by German photographer Ralf Bäcker. As the flyer for the event reads, “Women in particular start small businesses, build, work, and so provide for the family as small entrepreneurs and skilled workers.” In the photos of Gyumri on display, it is above all women who are doing the work, in the past as in the present.

Promoting Awareness of Autism through Music and Art

April is World Autism Awareness Month, a time to learn about autism. Organizations offering help to people with autism use the opportunity to educate the public on their work and many, like the My Way center in Yerevan, invite the public to join them in celebrating their achievements. The My Way Socio-Rehabilitation and Vocational Training Day Care Center is a leading institution for helping children, youngsters and young adults with autism, not only in Armenia, but throughout the region.

Frankfurt Remembrance: Reflections on the Lausanne Treaty

This year’s central commemoration of the Armenian Genocide was held in the historic Paulskirche in Frankfurt, organized by the Diocese of the Armenian Church in Germany, the Central Council of Armenians in Germany, together with the Armenian Embassy in Berlin.

St. Paul’s Church was the place where the first freely elected legislators convened in 1848 to deliberate on the first democratic constitution for the nascent German state, a site comparable to Independence Hall in Philadelphia for Americans.

Celebrating German Publisher, Human Rights Activist Helmut Donat on His 75th Birthday

It is not only his family and friends who have reason to congratulate Helmut Donat on his 75th birthday; members of the Armenian community everywhere should join in as well. As a publisher, he has done more to educate the reading public on Armenia, its people and history, its tragedies and achievements, than any other German publisher.

Reflection during Lent with Alan Hovhaness

Music occupies a very special place during Lent. In Germany concerts, held mainly in churches, traditionally offer performances of music by Johann Sebastian Bach, the St. John and St. Matthew Passions in particular. In Glasgow, Scotland, musicians join with other artists during the 40-day period in a festival organized in collaboration with the Catholic Church. Known as LentFest, this year it included a concert by international pianist Alessandra Pompili, known also for her dedication to the music of Alan Hovhaness.

European Parliament Adopts Resolution Chiding Azerbaijan for Destroying Armenian Heritage in Artsakh

On March 10, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on “Destruction of cultural heritage in Nagorno-Karabakh.” The vote tally was 635 in favor, 2 opposed and 42 abstentions. It stands out for its clarity of purpose and demands for forceful, effective action.

Armenian Ambassador to Germany Yengibaryan: ‘Time to Set a New, More Ambitious Agenda’

The following interview was conducted with Viktor Yengibaryan, the new ambassador of Armenia to Germany, after his appointment was announced.

Armenian Artists Return Home

After 30 years’ living and working in Germany, two leading Armenian artists are packing up their canvases and brushes, their books and personal belongings, and will soon board a plane for Yerevan. Nona Gabrielyan and her husband, Van Soghomonyan, are an institution in Wiesbaden, the capital of the federal state of Hessen, located in the Rhine-Main area near Frankfurt.

Genocide Researchers Explore Denialism

On January 29, historians, human rights activists and students gathered in Berlin and via Zoom internationally for a lively debate on denial, an aspect of genocide studies that has become increasingly prominent in political developments. Organized by the Working Group for Recognition: Against Genocide, for Understanding among Peoples (AGA), the conference dealt with both the Holocaust and the Genocide against the Armenians and other Christian minorities in the Ottoman Empire.

Pictures at Exhibition Raise Profound Issues

Ambiguity lends a special quality to art. Not ambiguity as attempted deception, but as an invitation to explore what is unstated, merely hinted, or lends itself to multiple, even contradictory interpretations. An exhibition that opened on November 9 at the Yerevan Modern Art Museum is a perfect example. Guy Ghazanchyan is the artist and the title of the exhibition is “ԱԿԱՆատես” [Akanatehs], which contains a double meaning, through a play on words.

The Dynamic Development in Armenian-German Relations

Exclusive interview was conducted by Muriel Mirak-Weissbach with Ashot Smbatyan, Ambassador of the Republic of Armenia in Berlin, at the conclusion of his term, on November 26. 2021.

"Taking a retrospective look at the Armenian-German relations of the last six years, it would not be an exaggeration to describe them as dynamically developing and reflecting the interests of the two countries at both bilateral and multilateral levels."

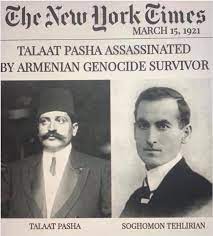

Talaat, Tehlirian and the Pursuit of Justice

A hundred years ago Berlin was the scene of a criminal trial which was to go down in history. The Armenian Soghomon Tehlirian stood trial for the murder of Talaat Pasha, whom he shot on March 15, 1921 in broad daylight. Talaat was the former Interior Minister of the Young Turk regime who had masterminded and directed the genocide against 1.5 million Armenians and countless other Christian minorities.

Celebrating Inclusiveness through Art

Art is inclusive. Creativity, that uniquely human characteristic, is by definition universal. No matter what age or sex, from what culture or geographical region, every human being is endowed with the ability to create, and art is the way we celebrate that capacity.

Nowhere is this more evident than in cultural events featuring youngsters with disabilities. In Yerevan earlier this month, the «ԿՈՂՔ ԿՈՂՔԻ» “Side by Side” State Musical Inclusive Art Festival took place, presenting both the visual and performing arts.

Is Armenia a Geopolitical Football?

As the tensions between Azerbaijan and Armenia escalated in Summer 2020, it became clear to some think tanks and specialists in Germany that this was a kind of proxy conflict. Behind the historical conflict between the two countries, they saw a clash of interests between regional powers. Azerbaijan’s active military engagement role led to a questioning of defined borders and a shift in the balance of power, reigniting a long-term conflict.

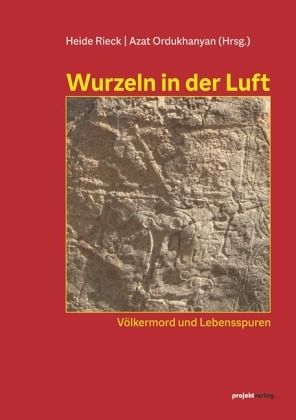

New Anthology in German Looks at Genocide Aftermath

On September 21 Armenians throughout the world celebrated 30 years of independence for the Republic of Armenia. In official venues, like the Armenian Embassy in Berlin, the event was commemorated in the presence of public figures from political life. It was an occasion to reflect on 1991 and to cast a glance to the future, enriched by the lessons learned in the intervening period. On that same day, a group of Armenians and Germans, scholars, writers, civil society activists and others, convened in a virtual Zoom meeting, to offer insights into events of the far more distant past, the genocide a century ago.

Berlin Greek Orthodox Community Commemorates Genocide Victims

Every year in mid-September, members and friends of the Greek Orthodox community in Berlin gather at the Luisenkirchhof III cemetery to honor the memory of the victims of the genocide. On September 11, the Day of the Open Monument, participants took part in a tour of the cemetery led by Dr. Tessa Hofmann, co-founder and spokeswoman of the organization behind the initiative (FÖGG). On Sunday, September 12, she delivered an address at the commemorative ceremony, where a wreath was laid, and Archimandrite Dr. Stefan L. Toma, of the Greek Orthodox Church of Christ’s Ascension, offered requiem prayers.

Ars Musica Winds Up Concert Tour of Armenia

The members of Ars Musica agreed that the musical and cultural highpoint of their extensive visit was the final event. The renowned men’s chorus from Thuringia, Germany, was concluding a two-week concert tour that renewed and enriched their relationship to Armenia. The friendship had begun more than thirty years earlier, when many of today’s singers were members of a boys’ choir. In 1988, they had performed a concert in the city of Suhl, in solidarity with the victims of the Armenian earthquake. And in 2018 the Ars Musica singers commemorated the anniversary again with a major choral performance.

Seeking Justice after War

It was supposed to be the war to end all wars. But once it had ended, there was “no peace to end all violence.” On the contrary, even with the establishment of the League of Nations, which was to usher in the new era of peace, the world witnessed new forms of nationalism and imperialism, new conflicts, and continuing human suffering on a mass level. At the same time, new concepts of humanitarian intervention and international law developed.

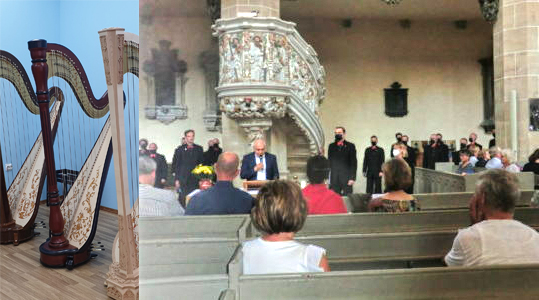

Ars Musica Brings Grand Concert Harp to Gyumri

GYUMRI —Sunday, August 22. Gyumri, in the Black Fortress. About 300 guests gathered for a very special event. Ars Musica, a renowned men’s chorus from Germany, was on a concert tour in Armenia, having already performed in Tatev, Yerevan and at the Geghard monastery. After Gyumri, they would continue with performances in Gavar, the Sevanavank monastery, Litschk and Echmiadzin.

Artist Archi Galentz Marks a Half Century with What He Loves Best: Art

If you are an Armenian artist living in the German capital and you are about to turn 50, how should you celebrate the occasion?

Archi Galentz has decided to mark the event with an exhibition of a special kind.

Among the working titles he considered were “The First 50” and “Stages of Formation of the Midlife Crisis of an Arriereguardist,” but the show was not to be a retrospective.

Gold Medals for the Little Singers of Armenia

All eyes this summer were on the Olympic games, where Armenia competed successfully in several disciplines. Some weeks earlier, another international event took place, albeit not followed by so many millions of television viewers, but in which the Armenian contestants walked away with gold, and not only once.

A Harp for Gyumri

The cathedral in Halle, Germany, is huge, but once the doors closed and visitors had taken their seats, it was almost full — at least as full as it could be under pandemic conditions of social distancing.

Akhtamar Quartet Brings Healing Power of Music Armenia

Four young musicians from Brussels have just concluded a concert tour of Armenia, bringing the healing power of music to layers of the population still suffering the impact of war and pandemic disease.

The Akhtamar Quartet made its musical and solidarity journey through Armenia in the first three weeks of June, performing 20 concerts (all free of charge) in 15 days.

Ars Musica to Perform in Armenia

In 1988, after massive earthquakes struck Armenia, leaving behind a trail of death, injuries, crumbled buildings and shattered lives. “That December,” Ambassador Ashot Smbatyan would later recall, “many came to our aid, from all over the world. But the help that came from the Suhl concert moved me in a special way.” The Armenian diplomat in Berlin was referring, 30 years later, to a concert of the Boys Choir from the Thuringian city of Suhl.

Cultural Roots of Armenian Identity

What does it mean to be Armenian? What is Armenia’s national identity? How do its citizens perceive it? And those in the diaspora?

Over the last 30 years, the country and its people have experienced political upheaval through the collapse of the Soviet Union, the subsequent economic crisis and years of war, decades of struggle to shape a new self-conception and define a meaningful role in the regional and international context. The most recent phase of transformation, ushered in by the “Velvet Revolution” three years ago and followed by the catastrophic 2020 war in Nagorno-Karabakh, remains open, more questions raised than answered.

April 24 in Germany:

against Genocide, Then and Now

The Working Group for Recognition: Against Genocide, for Understanding among Peoples (AGA) issued a call for a vigil on April 24, 2021 opposite the Turkish Embassy in Berlin. Among the 250 persons who joined were participants in a demonstration organized by an Armenian association, HayStab. As became clear from the posters, leaflets and statements, the focus was not only on the demand for Turkey to assume historical responsibility for the genocide, but also on Germany’s involvement, Azerbaijan’s military aggression against Nagorno-Kara- bakh and its continuing refusal to release prisoners.

Alan Hovhaness: Armenian Composer, Universal Spirit

Alan Hovhaness: Armenian Composer, Universal Spirit

“I welcome you to this special event dedicated to the 110th anniversary of the birth of Alan Hovhaness, one of the greatest composers of the 20th century.”

This is how Dr. Ara Ghazarians, curator of the Armenian Cultural Foundation (ACF) opened a moving tribute on April 17. Conducted over zoom, the commemoration was organized by the Board of Trustees of the ACF, and co-sponsored by Amaras Art Alliance and the Friends of Armenian Culture Society and Alessandra Pompili.

My Way Celebrates Creative Inclusion for Those with Autism

My Way Celebrates Creative Inclusion for Those with Autism

April had started with rain in Yerevan, one wet day after another, and the organizers of the My Way Center prayed for sunshine. On April 6, the day they had chosen for the event, board member Sona Petrosyan, looked up at the cloudy sky that morning and said to herself, “Dear God, please send us some sunshine around noon.” Right then a dove spread its wings and flew towards her, then soared gracefully up to the sky, and she said to herself, that must be a good omen.

Shenorhavor Tzenundehd (Happy Birthday) Heide Rieck!

Shenorhavor Tzenundehd (Happy Birthday) Heide Rieck!

Under normal circumstances we would have organized a huge birthday party. There would have been music — Armenian music — and poetry and dancing, shish-kebab, with all the trimmings, paklava and Ararat cognac. Friends would have come from all over Germany — Armenians, Turks, Kurds, Germans, young and old, colleagues and students, as well as family members. No one would want to miss Heide Rieck’s 80th birthday party.

Ceramics Lab for People with Special Needs

Ceramics Lab for People with Special Needs

“It seems that our dreams have come true!” This is how Alya Kirakosyan put it when the ceramics lab opened this month. Kirakosyan is the director of Warm Hearth, a house in the village of Geghanist in Ararat marz, not far from Yerevan.

Responding to Violence through Art

Responding to Violence through Art

Every message I have received from Armenia over the holidays has expressed the notion that 2020 was a terrible year for everyone, and doubly so for Armenia. Not only has the pandemic brought sickness and death to many families, but the war in Artsakh has left the country traumatized, many young people wounded or killed in battle.

Musicians in Germany Raise Funds for Artsakh

Musicians in Germany Raise Funds for Artsakh

It was in the middle of October, not long after the outbreak of the war in Nagorno-Karabakh. Amalia Safaryan, a young pianist living in Marburg, called her friend, Seda Nahapetyan, a singer a Giessen. Her message was urgent: “We have to do something; we’ll go crazy if we just sit around waiting for the war to end. We have to do something for our country!”

Ruben Hakhverdyan Trio plays at ‘My Way’ Children’s Center

At My Way Socio-Rehabilitation Day Care Center for Children and Teenagers with Autism, children, parents, guests, teachers and staff therapists joined in the newly equipped multi-functional performance hall for a live concert on December 25.

Hrant Dink Remembered in Germany

Fourteen years have passed since Hrant Dink was assassinated in front of the offices of Agos newspaper in Istanbul. Since then, conditions for journalists, intellectuals and pro-democracy activists inside Turkey have worsened and the new war in Nagorno-Karabakh has engulfed Turks and Armenians again in violent conflict. At such a time of political repression and renewed military aggression, commemorating the anniversary of his death assumes special significance.

Armenian Choirs Join in to Sing for Peace

Armenian Choirs Join in to Sing for Peace

On December 19, six choirs from Armenia and Artsakh joined seven other choirs to perform on World Choral Day.This event, organized every December under the auspices of the International Federation of Choral Music, attracts thousands of singers who organize concerts around the middle of the month

Orchestra for Peace Performs in Berlin

Orchestra for Peace Performs in Berlin

Walking up towards the Brandenburg Gate, you see on the ground a myriad of small red votive candles, lined up in rows to form a huge cross. Behind it, on a stage, an orchestra plays a piece by Komitas. It is November 6 in Berlin, and people have been gathering throughout the afternoon, to take part in an event dedicated to peace in Berg Karabakh. They have been visiting information stands to find out about the conflict, have seen works on exhibit by Berlin artist Mischa Badasyan and have listened to speakers from the political and cultural world address the issue.

Group Calls for German Government to Recognize Artsakh

Group Calls for German Government to Recognize Artsakh

On November 25, the French Senate voted almost unanimously to recognize Artsakh, as reported in the Mirror-Spectator. The following day, the Central Council of Armenians in Germany (ZAD) issued a press release, thanking the French Senators for their action, and calling upon Germany’s Bundestag (Parliament) to follow suit, and demand recognition on the part of the federal government.

Discovering the Wines of Armenia

Discovering the Wines of Armenia

Armenia has not only brandy to tempt the palate. Together with its legendary cuisine, it also has a wide range of wines, product of a long history of winemaking. Recently two Germans have launched an initiative to publicize this little known fact. Michael Richter comes from Bernkastel on the Mosel, famous for its own wines.

Where Does Germany Stand?

Where Does Germany Stand?

Since the renewed outbreak of war in Nagorno-Karabakh, efforts have been underway on an international level to stop the fighting, and lay the basis for a political solution. The central institution involved has been the Minsk Group, which came together in 1994 at the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Budapest summit. Its permanent members are Belarus, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Finland, Turkey, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Co-chairmen are the Russian Federation, the United States and France.

Berlin Commemorates Victims of Iznik Massacres 1920

Berlin Comme-

morates Victims of Iznik Massacres 1920

At the Luisenkirchhof cemetery in Berlin-Charlottenburg, large, imposing structures stand in solemn commemoration of genocide victims. These are the Altars of Remembrance, dedicated to the memory of the more than 3 million Christian genocide victims in the Ottoman Empire. They are the Armenians, Pontic Greeks and Syrian Orthodox who were massacred. The altars are the work of the Promotional Society for the Ecumenical Monuments for Genocide Victims of the Ottoman Empire (FÖGG), which plans commemorative events several times a year.

Petitions, Calls for

Political Mediation Continue

Petitions, Calls for

Political Mediation Continue

As the war in the South Caucasus enters its second month, Armenian organizations in Germany are redoubling their efforts to urge government authorities in Berlin and in Europe to finally take effective action.

Book Dedicated to Martyred Poets Launched in Germany

Book Dedicated to Martyred Poets Launched in Germany

On September 18 the Lepsiushaus in Potsdam hosted a book launch of the volume, Todesvision. Eine Hommage an die ermordeten Dichter Armeniens (1915-1945) (Vision of Death. Homage to Armenia’s Murdered Poets (1915-1945)).

The poems were translated from Armenian by Dr. Gerayer Koutcharian and rendered poetically into German by Prof. Tessa Hofmann

Tessa Hofmann Book Pays Tribute

to Poets of the Genocide

Tessa Hofmann Book Pays Tribute

to Poets of the Genocide

On April 24, 1915, the Young Turk regime rounded up hundreds of Armenians, intellectuals, artists, writers, teachers, religious leaders, community elders in what Prof. Tessa Hofmann has called “elitocide.” It was the alarm that sounded the beginning of the Genocide that was to eliminate all layers of the population, young and old alike. A new book has just appeared in Germany dedicated to the poets murdered in that process.

Tribute to Karen Vardanyan: A Man with a Vision for Armenia’s Future

Tribute to Karen Vardanyan: A Man with a Vision for Armenia’s Future

With the passing of Karen Vardanyan, Armenia has lost a dedicated citizen, a creative engineer, an indefatigable organizer and passionate educator, a fine human being. He died on July 10 in Yerevan at age 57.

Germany’s Armenians

Respond to Aggression

Germany’s Armenians

Respond to Aggression

“Make dolma not war.” That is the message that Haykanush Sechelyan transmitted on a poster during a demonstration in Hamburg, Germany on August 1.

Art Is More Powerful than War

Art Is More Powerful than War

When Azerbaijan attacked the Tavush region in July, Armenians everywhere responded with protest demonstrations. In Berlin, as reported in this newspaper, several cultural associations came together to organize an artistic response, with an exhibition that opened on August 9 and ended on August 30. Hosted by the Wolf & Galenz Gallery in Berlin, it was entitled, “Armenia: Grace and Violence. Images of Landscapes and Traces of War.”

Bridging Social Distancing for People with Autism

Bridging Social Distancing for People with Autism

If you think teaching music, dance and art online is a challenge, consider what faces educators whose students are children and youngsters with autism. The My Way Socio-Rehabilitation Center for Children and Teenagers with Autism in Yerevan provides education and therapy for such pupils with special needs, usually with a full week’s schedule of classes in their spacious buildings. When the pandemic crisis hit Armenia in March, the center was functioning, but soon had to close, like other schools, first for a brief pause, then for an indefinite period of time.

Making Art and Music in a Lockdown in Armenia and Germany

Making Art and Music in a Lockdown in Armenia and Germany

“It’s so hard to give vocal lessons by Skype. It’s terrible!” Lusine Arakelyan is an opera singer who teaches at the Aleksey Hekimyan Music School in Yerevan. Since the lockdown started in response to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, she, like most other Armenian teachers, has been forced to expand her pedagogical skills with patience and creativity. She and her students bridge the social distance through the computer, and the challenge is significant.

I Stay Home,

I Remember

I Stay Home,

I Remember

Every year on April 24, the French Cathedral in Berlin welcomes Armenians and Germans to commemorate the anniversary of the 1915 genocide. I usually travel to the capital for the solemn ceremony. In Frankfurt, the historic Paulskirche is the venue for a parallel ceremony that my husband regularly attends.

Every year, but not this year.

Armenian Artists

in Times of Corona Pandemic:

Berlin

Armenian Artists

in Times of Corona Pandemic:

Berlin

The coronavirus pandemic shutdown has affected every aspect of life here in Germany, from schools to shops, from factories to farms. Social encounters that have always been part of our daily life, in restaurants, bars and cafes, fitness studies, public parks and playgrounds, have undergone a drastic redefinition, distancing has replaced engagement, friendly personal exchange stifles under the protective cloth of the face mask.

Armenians,

Autism and the Emirates

Armenians,

Autism and the Emirates

It was February 17 in Zvartnots airport, and two young men shared the stool at the red piano and played with energy and passion. It was before the Coronavirus pandemic had brought international travel to a halt, and they were expressing their excitement about their imminent flight.

The Start of a Successful (Medical) Relationship

The Start of a Successful (Medical) Relationship

Five years ago, the German-Armenian Forum came into being upon the initiative of Albert Weiler, a member of the Bundestag (Parliament) from the Christian Democratic Party (CDU). The aim of the new association was to intensify relations and promote mutual understanding between Armenia and Germany at all levels, from government to parliament, among professionals, students and youth. And it has been a success story.

Post-COVID Art Blossoms again in Berlin

Post-COVID Art Blossoms again in Berlin

Slowly, cautiously and with painstaking care to ensure the safety and health of visitors, Archi Galentz and Andreas Wolf welcomed art lovers to their gallery in the German capital for the opening of a new exhibition on May 29. It was the first time since the Coronavirus pandemic had shut down normal life in Berlin that people could gather in such a setting. To be sure, guests had to register beforehand and could enter the gallery only five at a time, so that each would always have 20 square meters space.

Calls for Action on Hagia Sophia

Calls for Action on Hagia Sophia

On July 12, two human rights organizations based in Berlin issued a joint declaration on the decision taken a day earlier to alter the status of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Both organizations have been in the forefront of efforts to gain official recognition of the genocide, efforts that led to the resolution in the German Bundestag (Parliament) passed in 2016.