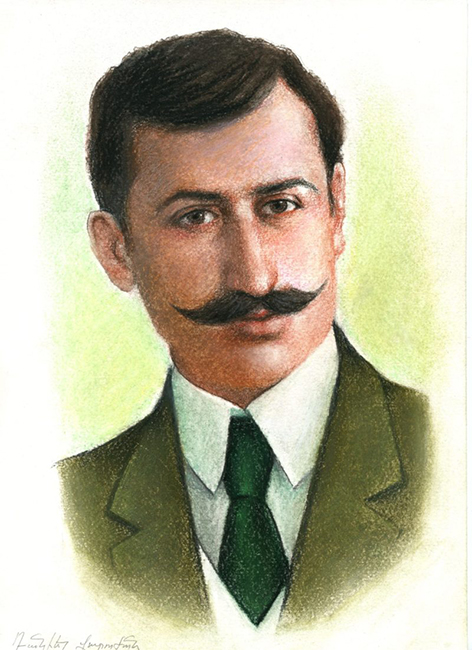

Daniel Varoujan

Tessa Hofmann Book Pays Tribute

to Poets of the Genocide

By Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

BERLIN, AUGUST 20, 2020 — On April 24, 1915, the Young Turk regime rounded up hundreds of Armenians, intellectuals, artists, writers, teachers, religious leaders, community elders in what Prof. Tessa Hofmann has called “elitocide.” It was the alarm that sounded the beginning of the Genocide that was to eliminate all layers of the population, young and old alike. A new book has just appeared in Germany dedicated to the poets murdered in that process.

Tessa Hofmann is well known as a pioneering genocide researcher in Germany, and her books and articles, published in German and English, are required reading for serious students of the genocide against the Armenians, Greeks and other Christian minorities in the Ottoman Empire. She has also been a leading campaigner for recognition of the Armenian Genocide, and has launched initiatives to commemorate the victims, like the Promotional Society for the Ecumenical Monuments for Genocide Victims of the Ottoman Empire (FÖGG). Hofmann is also chairwoman of the AGA, the Working Group for Recognition, against Genocide, and for Understanding among Peoples, which issued a joint declaration with the FÖGG to protest of the Turkish decision to covert the Hagia Sophia into a mosque.

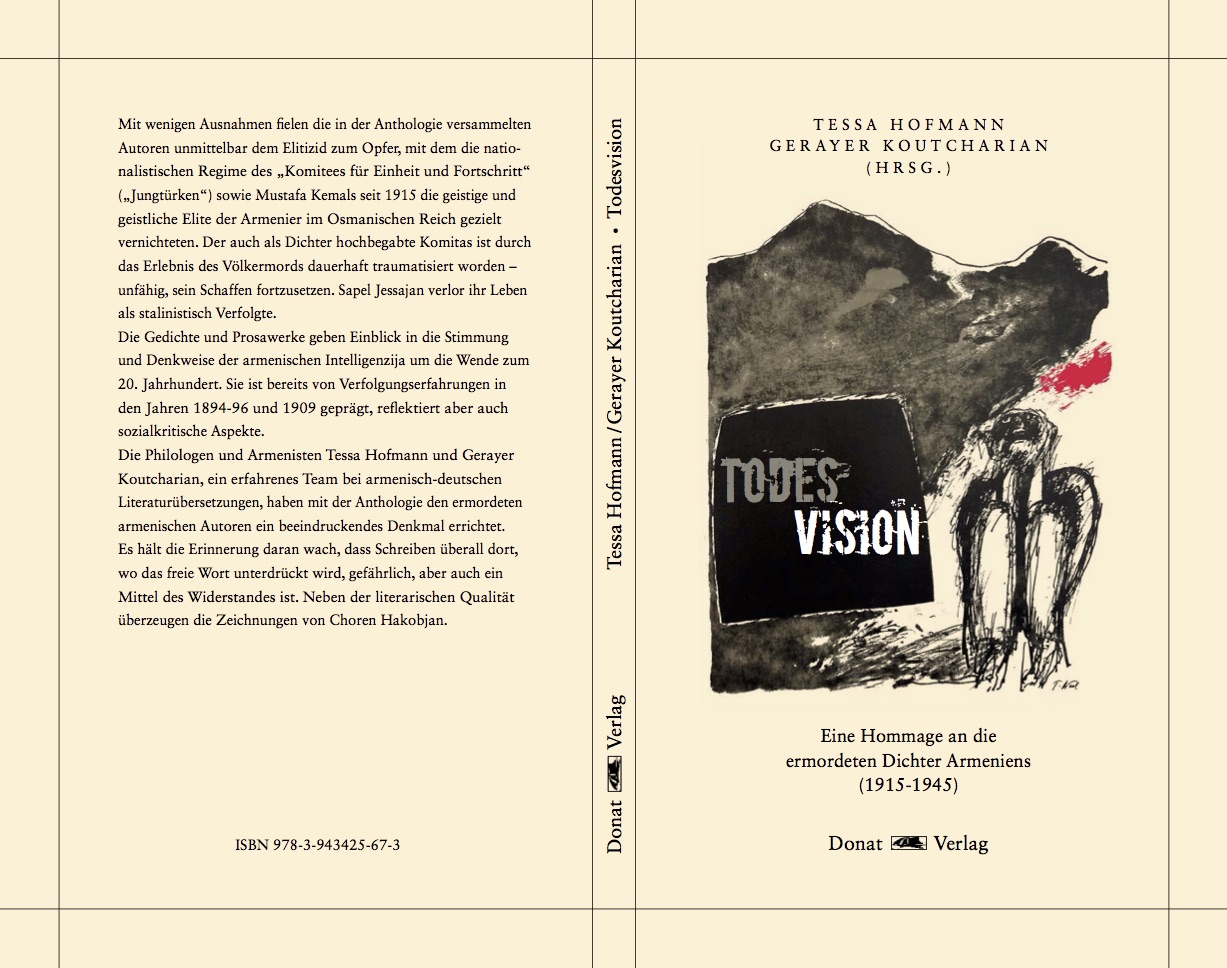

Recently, the Berlin-based scholar has published works of a literary nature. In 2019, she issued a book of fables and fairy tales, featuring works by Hovhannes Toumanyan. The German translation was the result of a collaborative effort with Gerayer Koutcharian, who is a professional translator and teacher of Old and Modern Armenian. That same year her own novel, Tauben und Raben. Ein historischer Roman aus dem alten Irland, (Doves and Ravens: A Historical Novel from Old Ireland) appeared. And in early summer 2020, a volume of poetry and prose was released, translated into German again with Koutcharian. The title is Todesvision. Eine Hommage an die ermordeten Dichter Armeniens (1915-1945) (Vision of Death. Homage to Armenia’s Murdered Poets (1915-1945)). It was published by Donat Verlag in Bremen, which is well known for numerous works dedicated to Armenian history and culture. The volume is illustrated with ten drawings by Khoren Hakobyan, portraits of the authors.

“The collection Todesvision,” we read in the introduction, “came into being in commemoration of Armenian authors murdered in the first half of the 20th century. The anthology contains poetry, fiction and non-fiction prose by nine West Armenian authors. With the exception of Vahan Tekeyan, Zabel Yesayan and Intra they were persecuted and killed during the elitocide of Armenian intellectuals in the Ottoman Empire.” Zabel Yesayan was one of the “few women … who were on the police lists of names targeted for arrest. Like Vahan Tekeyan, she eluded capture through lucky circumstances. In this collection, she stands as a representative of those authors of West Armenian background who under Soviet rule were victims of the double victimization of Armenians in the 20th century: the second elitocide 1936-39 as well as the deportation of West Armenian ‘Repatriates’ in 1949.”

The selections include accounts not only of the 1915 genocide but also the Hamidian massacres in 1894-96 and 1909.

The anthology grew out of a series of public readings organized in 2014 and 2016 that took place on April 24 in Berlin and Jena, and the form reflects this origin. It is not merely a collection of short works but a poetical journey through the experience, guided by the testimony borne by one of the leading figures. The priest Grigor Balakian was one of the clergymen seized in the mass arrests on April 24, one of the few to survive and record the entire drama.

The saga begins with the arrests. The first poem, “It is Springtime,” is one of the hundreds of folk songs collected by Komitas, musicologist, composer and priest, who was among those arrested that night. A brief biographical sketch introduces the celebrated figure, and Balakian relates how in the coach they shared, Komitas began to display signs of the psychological trauma that would torment him for the rest of his life.

“Dream with No Way Out” and “Aurora” were composed by Artashes Harutyunyan, poet, critic and translator. Known by the pseudonym Garo, he represents the intellectuals arrested in the provinces and taken to their deaths.

Siamanto, considered the most significant West Armenian poet along with Daniel Varoujan, left Constantinople in the period of the Hamidian massacres and lived in exile in Cairo, Geneva, London and Paris, where he was influenced by French culture, especially the symbolist poet Paul Verlaine. His first poem, composed in 1898, lends its name to the title of the volume, “Vision of Death.” Like many other intellectuals, he returned to Constantinople following the 1908 revolution; in 1909 he learned of the Adana massacres, which inspired his “Red News from My Friend.” The Dantesque images of violence and suffering will be echoed in works of other poets, for example, Vahan Tekeyan. Poet, teacher and social worker, Tekeyan was abroad in 1915, thus escaping the Genocide. His “survivor guilt” led him to doubt his faith in God, as expressed in “Diaspora,” a poem presented together with “Deportation.” In “You Will Fall,” he addresses the aggressors, foretelling their ruinous end and giving voice to the “hatred and wrath” of the victims, that will reappear in works by other poets.

Daniel Varoujan, we learn in the biographical sketch, studied with the Mekhitarist order in Venice and Ghent, and on his return, directed the Armenian School in Constantinople. Arrested on that fateful April night, he was deported with the rest, first to Çankiri. Later he was en route to Ankara, together with four others, when halted and murdered by a band of Kurds. Balakian’s recollection depicts them as they were leaving for Ankara, knowing that death awaited them. If in the poem “Dedication” he sings praise to the fatherland, and to its brave warriors who will seek revenge, in “Seas of Wheat” he paints a landscape whose waves of wheat roll like the waves of the sea. And in “Four Corners” he expresses a yearning for peace, development, joy and prosperity in all parts of the world.

A poet who suffered a similar fate was Ruben Sevak, who had returned to Constantinople after studying medicine in Lausanne. He too was dispatched to Çankiri and was to travel on with four other deportees, with assurances by the vice governor that they would be unharried. Instead, Kurdish murderers together with police officials intercepted them, and, after killing them, divvied up the 450 gold pieces they had sewn into their clothing. Again Balakian records the tragic event, commenting, “This way our nation lost … two talented poets and five loving fathers of small children. But unhappily we had hardly time to mourn them, because new massacres and rivers of blood awaited.” The short poem “Armenia” by Sevak concentrates in six lines images of the terror and suffering of the refugee, the starving, the murdered.

Three prose pieces follow, the first by Yervand Srmakeshchanlyan, a teacher and author known as Yeruhan. Writing in the late 19th century realist style, he composed short stories about the life of simple people in Bulgaria, where he had sought refuge. One such story, “The Washerwoman,” tells the tale of young Surbik, who eked out a living by washing the clothes of sailors, fishers and other workers in a port. One day she spies a handsome young man, a fisherman named Hovsep, and manages to win him as a client. She picks up his clothes and washes them with fervor and loving care, and her affections are answered by the young man, who satisfies her wish to receive an Easter dress instead of money for her labors. It comes to the point that he proposes marriage and her joy is complete. But there is no happy ending; when she returns to the port, she learns that he has drowned in a tragic accident. She gathers up his clothing, takes them back to her room, washes them with particular care and energy, torn between laughter and sobs.

Krikor Zohrab was a lawyer who defended Armenians and, under political pressure, fled to Paris, where he lived until 1908. Following the Young Turk revolution, he returned and was elected member of the Ottoman parliament, and of the Armenian National Assembly. In 1915 he was arrested along with another Armenian parliamentarian, Vardkes Serengulyan, and deported to Diyarbakir to be tried by a military tribunal. They never reached their destination, but were apprehended on government orders by brigands and near Urfa brutally murdered.

He composed poems and essays, and between 1909 and 1911 published three collections of short stories. “The Wretched Girl” is the story of Tigranuhi, an 18-year-old orphan, whose beauty made her the envy of her sisters. Her aunt married her off to a young coal miner, but the poor lad broke a leg in a mining accident and lost his job. Just at that juncture, Hadja Tyurik, an agent who recruited chambermaids for wealthy households, appeared and offered to take Tigranuhi to Bolis to work for Madame Surbik, wife of Monsieur Rasar.

Happy in her new job, in a wealthy home with other servants, good accommodations and pay, Tigranuhi worked gladly and sent her salary home to her husband. Meanwhile, the young, lusty son of the man of the house becomes obsessed by Tigranuhi’s beauty and seeks every opportunity to approach her. The girl one day tells all to the lady of the house, who defends her son as simply a boy enchanted by her beauty. Hadja Tyurik reacts similarly, saying she should be happy to have a gentleman seek her favor. The young man, whose mother showers the young girl with gifts, succeeds in seducing Tigranuhi. For two years, the affair continues, until the chambermaid becomes pregnant. The lady of the house confronts her, calls for Hadja Tyurik to come immediately and remove the “slut” from her honored home. Claiming the girl had become pregnant by a male servant, and refusing to acknowledge that her son was responsible, in the end she has to admit that it was the son, and makes amends financially.

Four years later, Tigranuhi’s husband dies of a lung ailment and shortly thereafter, her young son also dies. With determination, Tigranuhi pulls together all the money she has to pay for a dignified funeral, with candles, priests and a closed coffin for the child. She purchases two plots in the graveyard and visits her son’s grave on commemoration days. When asked where she has been, she replies happily, “I went to my child, Madame!”

Rupen Zartarian was a teacher who was arrested in 1903 and jailed for a year for his political activity in the Dashnag party, then went into exile in Bulgaria until the 1908 revolution. He was a teacher in Constantinople, worked with the Armenian magazine “Shamanak” (“Time”), and published the Dashnag party organ Azadamard (“Freedom Fighter”). He was also a poet and prose writer, as well as a translator of classics from French and English literature. On April 24, 1915, he was arrested along with the entire editorial board. He was supposed to appear before a military court but was assassinated by brigands.

In “A Wolfhound,” he tells the allegory of a proud mountain dog that had defended sheep until an injury forced him to seek a new life in the city. There, he encounters the pack of wretched hounds, whose miserable life disgusts him; better to fight the wolves and perish than to degrade oneself and beg – is the moral he draws.

Zabel Yesayan managed to flee and found exile in Soviet Armenia. Because she defended poets Yeghishe Charents and Axel Bakunts, she was declared an enemy of the people in 1937. Her death sentence later turned into banishment. The details of her death remain unknown. A selection from her 1911 book, In the Ruins, presents the heartrending story of one Genocide victim, an old woman. As she tells it herself, first, her husband is taken away to be killed. Convinced by her son that it is worth converting to Islam to survive, she reluctantly agrees. She does survive with both son and daughter, but the son is eventually killed and the daughter abducted. All her attempts to obtain justice fail.

The last pieces are by Intra (Diran Chrakian), a poet, painter and teacher, persecuted as a member of the 7th Day Adventists. The atrocities in 1915 left him mentally unbalanced and in 1921 he was arrested and deported. The poems “Desire,” “On the Blue,” and “The Wish” are verbal paintings, whose vibrant images from nature express a yearning for the innocent life. The last lines of “Compassion and Love” read:

“For, the passion of the poet is nothing more

Than mourning for the lamentable ephemeral

And a love song to immortal creation.”

This small, scholarly volume is incredibly compact and powerful, a little jewel. The short pieces cover a vast range of human experience, depicting the pain and suffering of the victims, their yearning for justice and harmony; they express existential torment and doubt, as well as faith in the promise of a better future. There is sadness, hope, pride and despair — and also a desire for revenge — yet even in the direst of circumstances, dignity prevails. The poems are striking in their emotional force, enhanced by brevity of form, while the prose pieces testify to a rich popular literary culture in which the plight of humble people provides the subject for storytelling.

Koutcharian and Hofmann have worked together as a team, the former translating from his mother tongue into German, and the latter, recasting the idea-content in German poetical form. Citing titles and verses here in English necessarily represents a further departure from the original, and cannot do justice to the extremely convincing German rendition. The drawings are simply wonderful; they evoke the art of portrait photographs so familiar to those of us in the diaspora who cherish the images of the grandparents and great-grandparents we never knew.

(The authors’ names in the German edition are given in Armenian script, and are transliterated into Eastern and Western Armenian, according to German phonetics. Here I have transliterated for an English-speaking reader, and apologize for any errors.)