Talaat, Tehlirian and the Pursuit of Justice

by Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

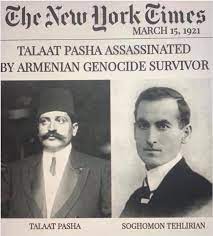

BERLIN, NOVEMBER 25, 2021 — A hundred years ago Berlin was the scene of a criminal trial which was to go down in history. The Armenian Soghomon Tehlirian stood trial for the murder of Talaat Pasha, whom he shot on March 15, 1921 in broad daylight. Talaat was the former Interior Minister of the Young Turk regime who had masterminded and directed the genocide against 1.5 million Armenians and countless other Christian minorities.

In the last week of October 2021, a group of human rights activists, historians, actors, musicians and jurists joined to commemorate these historic events, retracing the steps and actions of the protagonists, to reflect on their significance in the development of fundamental concepts of international law.

The Working Group Recognition – Against Genocide, for Understanding among Peoples (AGA) organized the commemoration in three events on October 24, 26 and 29: the first was a guided tour by genocide scholar and AGA Chairwoman Tessa Hofmann, down the Hardenbergstrasse, the street in Berlin where Tehlirian had shot and killed Talaat; the second featured a lecture by Hofmann on the importance of the subsequent trial in legal history, accompanied by readings from the trial testimony and from literary works dealing with the Armenian Genocide. The final event was a condensed re-enactment of the trial, held in the very same courthouse where the legal proceedings had unfolded.

Dr. Gerayer Koutcharian, AGA founding member, explained why Armenians commemorate the Hardenbergstrasse. In the genocide that began under Sultan Abdul Hamid II in the late 19th century and reached its climax in 1915-1923, Koutcharian said, an estimated “three million Christians were killed and more than 2 million more expelled and deprived of their citizenship.” The motivation? To establish a “Great Turan” of Turkic-speaking peoples stretching from the Adriatic to China, a vision, according to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, that is still being pursued in the unlawful aggression in Artsakh.

Hundreds of thousands of Genocide survivors, Koutcharian said, were “morally and spiritually broken” when they learned that the perpetrators had found refuge in post-war Germany, and “thirsted for revenge.” Thus the importance of this site in Berlin: “When Armenians come to Berlin,” he said, “they look for the place where they feel Soghomon Tehlirian in 1921 reestablished the dignity of their people. And that is why they go, their heads held high, to the Hardenbergstrasse.”

The impact of those events was to be felt not only in Germany and on the Armenian community, but worldwide, and forever after, as Hofmann detailed in a speech, “From Assassination to UN Convention: The Berlin Criminal Trial against Soghomon Tehlirian and Raphael Lemkin’s Consequences for International Law.”

Hofmann reviewed the political background of the dramatic events in Berlin, beginning with reference to the “Armenian Question,” the reforms that the European Great Powers listed in the 1878 Berlin Treaty and demanded the Ottoman Empire introduce. After 25 years of inaction, Turkey under the Young Turk regime, agreed in 1913, but took no action. As the German theologian Dr. Johannes Lepsius would note in his trial testimony, the Young Turks in 1913 threatened that, unless the Europeans desisted from demanding reforms, something would happen that would make the Hamidian massacres look like child’s play.

After the massacres began in spring 1915, the Great Powers issued a warning that they would hold the regime responsible for crimes against humanity — introducing for the first time this concept. It was only after the war that the Ottoman authorities, under pressure of occupying Allied forces, pursued suspects and opened war crimes tribunals. Among the Young Turk leaders who were tried, convicted and sentenced to death, most had fled and would be brought to justice only later by Armenian avengers. Following Mustafa Kemal’s establishment of the republic, a general amnesty was declared on March 31, 1923, war criminal suspects were freed, and the triumvirs were later declared national martyrs.

In 1919 the Armenian Revolutionary Party deliberated measures which led to the founding of the secret network, Nemesis, tasked with executing the Young Turk mass murderers who had been sentenced in absentia. Hofmann described the Nemesis organization and its leading members, and listed the perpetrators it succeeded in assassinating, among them Talaat.

Hofmann provided a biographical sketch of Mehmet Talaat, detailing his direct responsibility for the deportation and massacres, as documented by contemporary as well as later sources. After the armistice and his escape, he lived under an assumed name in Berlin, protected by the German authorities until Tehlirian assassinated him. Under Hitler, Talaat’s mortal remains were transferred in 1943 to Turkey, where he was honored as a martyr, with mosques, plazas, streets, schools etc. named after him.

Hofmann followed with a biographical sketch of Tehlirian, who attracted the attention of Nemesis in March 1920, when he had assassinated Harutyun Mkrtchian, who had drawn up the list of Armenian notables to be arrested on April 24, 1915 in Constantinople. Tehlirian was invited to Boston and deployed by Nemesis to deal with Talaat, who headed their list of targets. During Tehlirian’s later trial in Berlin, no mention was made of Nemesis.

In evaluating the legal and historical significance of the trial, which ended in a not-guilty verdict for Tehlirian, Hofmann focused on the work of Raphael Lemkin, who was to coin the term genocide and lay the basis for the 1948 UN Genocide Convention. The Tehlirian trial posed questions of moral and legal rights to the young jurist, who was motivated by the need to define the crime of mass murder. It was the first time a foreign court had dealt with the Young Turks’ genocide against the Armenians.

Hofmann summarized the trial proceedings, stressing the German government’s desire to conclude quickly and to avoid a political trial by focusing attention on Tehlirian’s psychological condition. Thanks to the testimony by Johannes Lepsius and two Armenian survivors, this failed. Lepsius could provide documented evidence of the deportations, death marches and deliberate killings. The Armenian witnesses, Christine Terzibashian and the Very Rev. Grigoris Balakian (later a bishop), gave eyewitness reports; she had been deported with family members from Erzerum in 1915, whereas Balakian was among those arrested on April 24, 1915 in Constantinople and deported to Chankiri.

Bishop Grigoris Balakian

The Voice of a Survivor

Christine Terzibashian’s memory came alive at the Berlin event, in a moving speech by her youngest son. Unable to attend in person for health reasons, Armen Terzibashian sent greetings which were read. His mother, he said, spoke seldom and unwillingly about the deportations. He described her as “motherly, a strong personality, and the most modest and loving person” he ever knew.

Her “struggle for survival made her creative … which helped her later as a stateless person in a foreign country.” She had told her son about the “endless marches, walking by corpses and the dying, … without water or food, the continuous stench of death, a terrible thirst that left her tongue as rigid as a stone.”

At one point along the Euphrates, called Boğazı Kemach gorge, there were “so many corpses lying in the river that one could have crossed it without getting their feet wet.” She described acts of brutality on the part of the Turkish guards, who smashed her six month old son against a cliff and killed her parents before her eyes; only she and two brothers survived. After five years’ wandering, during which she found refuge among Kurds, she made it to Berlin with the help of a relief organization and there was reunited with her husband.

“The devil in a man’s shape,” as she described Talaat, was not able to break her, he said, marveling at her vitality. He ended with a warning, that xenophobia had not yet been defeated, and quoted Bertolt Brecht, “The womb from which that crawled is fertile still.”

Bea Ehlers-Kerbekian, an Armenian-German actress from Berlin, then assumed the role of Christine Terzibashian, and read from her testimony at the 1921 trial. In simple, direct language she described the death marches in gruesome detail. Kerbekian concluded the evening with two more readings, this time from works by the late Turkish-German author and human rights activist Doğan Akhanlı. The selections from his novel “Madonna’s Last Dream” and play, “Anne’s Silence,” both deal with the Armenian genocide.

Berlin District Court III

On October 29, the scene shifted to the courtroom itself, the very same place where Tehlirian stood trial for the murder of Talaat Pasha. In front of a group of invited guests present as well as those joining via Zoom, actors and actresses reenacted the spectacular trial in condensed, highly dramatic form. Following an introduction by Tessa Hofmann, Dr. Bernd Pickel, President of the Berlin Superior Court (Kammergericht), offered reflections on the special aspects of the proceedings, how they might be evaluated juridically and historically.

Stepan Gantralyan opened the proceedings with a song in Armenian, accompanied on the harpsichord by Vincent Julien Piot. Considered an unofficial national hymn, especially among members of the Diaspora, it is entitled “Cilicia.” The text is attributed to Nahapet Rusinjan (1819-1876). Bea Ehlers-Kerbekian took the role of Tehlirian, Tuncay Gary portrayed the judge. Birte Flint and Anja Haverland read the remaining parts.

The trial opens on June 2, 1921. It is a sunny day, huge crowds have gathered and the international press is on hand. The suspect, a thin, intellectual young man, enters, swearing in proceedings follow, a harpsichord sounds.

Hardenbergstrasse in Berlin

The accused takes the stand and answers questions, his name and family background. He lived in Pakarich, then moved to Erzinjan, where in June 1915 the deportation order came. The inhabitants had to leave in caravans and columns, the gendarmes robbed and plundered, and when one of them tried to take his sister, his mother protested; his parents were among the first to be killed. “I don’t want to remember that day any longer. I would rather die now, than describe that black day any further….”

Lepsius provides facts and figures: that there were 1,850,000 Armenians before the war, and where they lived; how 1,400,000 were deported, leaving fewer than half a million, 200,000 of them were from Constantinople, Smyrna and Aleppo.

The accused answers more questions, recounts how he fled to a village in the hills, where Kurds offered him refuge, then travelled farther to Persia, then Tiflis, then Almas, where he stayed a year. When he received news that the Russians had taken Erzinjan, he returned home in 1916, only to find the village almost deserted, his family home devastated. Overwhelmed, he fell unconscious. When he came to, he searched for money and found it where his family had buried it, took it and travelled to Tbilisi (Tiflis), where he stayed two years and learned Russian, from there to Constantinople after the war, then to Salonika. There, too, he had seizures, fell unconscious.

“I Am Not the Murderer”

The court clerk reads the charges: Soghomon Tehlirian, accused of killing Grand Vizier Talaat Pasha on March 15, 1921 in Berlin. Asked for his plea, whether he answers yes or no to the charges, Tehlirian responds, “No.” Defense lawyer Dr. Adolf von Gorden asks why he considers himself innocent, why he has a clear conscience, and he answers, “I killed a man, but I am not a murderer.” Did he not want to kill him? Yes, he did kill him. Yes, he had a plan, he says. He had had a vision: his dead mother had appeared to him and asked how he could be indifferent, knowing Talaat was there. “You are no longer my son,” were her words. And when he awoke, he decided to kill him.

Edward Apelian, secretary at the Armenian Consulate in Berlin, takes the stand. He lived at the same place as the accused, and could report having seen him during seizures he suffered. Has he ever spoken of Talaat, and a plan to kill him? No. Once, Apelian recalls, they had been reading a book by Lepsius about the massacres, but the accused didn’t want “to open old wounds.” Apelian had no idea that Talaat was in Berlin.

The Assassination

Tehlirian again on the stand: he explains why he moved to lodgings on the Hardenbergstrasse. Perchance he had seen men nearby at the Zoological Garden, who were speaking Turkish, and recognized Talaat, whom the others addressed as Pasha. Motivated by the vision of his mother, he decided to carry out his plan. From his new lodgings, he could observe Talaat; on March 15, he saw him on a balcony, then leaving the building. Tehlirian grabbed his pistol, went out, followed Talaat, crossed the street and shot him dead. Under questioning, Tehlirian describes every moment, how he saw blood, and crowds gathering. Knowing they would apprehend him, he fled, throwing away his weapon while running.

Nicholas Jessen, a merchant from Berlin, was at the scene of the crime and provides testimony that confirms what the accused has just said. And how did the assailant feel after having fired the shot? Tehlirian answers that, when taken to the police office, he felt a sense of satisfaction. “Even today I am still very satisfied with my action.” He again recalls his mother’s order to kill Talaat, and explains, he was so changed that he did not know he should not kill.

Deportations and the Young Turks

The court now hears testimony on the crimes of Talaat. Christine Terzibashian takes the stand, 26 years old and a survivor. In painstaking detail she describes how the deportation orders came in July 1915, and in four groups over eight days, the people of her town were sent out on foot, including her extended family of 21 people. With her own eyes, she saw all but three of them killed, and swore the orders had come from Constantinople. Men were tied together and thrown into the water, others killed with bayonets. One brother was beheaded and when her mother saw this, she fell dead. Christine, two brothers and her father managed to escape, but her father succumbed to sickness. When asked, “Is that all really true? Isn’t that fantasy?” she answers, “What I have reported is much less than the reality. It was much worse.”

Lepsius provides the political context to the massacres, reaching back to the 19th century, and presenting the Armenian question as “a creation of European diplomacy.” Despite the promises of the Great Powers to protect the Christians and to force through reforms, “not one of them lifted a finger to save them or even to punish the murderers.” Then, although the Armenians and Turks made the revolution together and their leaders supported one another, on April 24, 1915, hundreds of Armenian intellectuals were arrested and deported, only 15 would survive. “It was the Armenian intelligentsia of Constantinople.”

The next to offer testimony is one of those few survivors, Grigoris Balakian, an Armenian clergyman, who offers a first-hand account. Balakian reports on a meeting he and a Professor Diran Kelekian, who had been a newspaper editor, in Changiri with the Deputy Governor Asaf Bey. The latter had displayed respect for Kelekian, who had been his teacher, and also for Balakian, as a man of the church. He showed them a telegram, signed by Talaat, demanding to know “how many Armenians are already dead and how many still alive.” Both Armenians reacted with disbelief, until Asaf Bey explained that was an order to start the massacres. A member of the jury wants to know whose signature was on the telegram. Balakian replies, it was “Talaat, I saw that with my own eyes.”

Back to the accused, and the motives for his actions. Professor Dr. Richard Cassirer describes Tehlirian as a patient he examined twice in his practice in February. From the symptoms described, Dr. Cassirer had initially diagnosed epilepsy and prescribed medication, which had heavy side effects. But now, after having followed the court proceedings, he has to alter his diagnosis; it is not a real form of epilepsy, but rather seizures provoked by the trauma and shock of what the accused had gone through during the war years. Though not prepared to declare that the accused bore no responsibility for his actions, Dr. Cassirer suggests that §51 of the penal code be applicable, a clause that says a person is not punishable if mentally incapable at the time, temporarily insane.

The following day the court reconvenes, the prosecution and the defense present their final arguments. Defense attorney Dr. Johannes Werthauer stresses the historical significance of the case, that “the eyes of the world are on us,” and says the implications will be felt for a thousand years. His colleague Dr. Niemayer points also to the political implications, reminding the court that Germany had been blamed as complicit in the Young Turks’ crimes, indeed it had been charged that “the Germans were the real Talaats in Turkey.” A not guilty verdict, he said, would rectify this; and “the world will see acquittal as an act of higher justice.”

Otto Reinicke, Chairman of the Jury, delivers the verdict: Not guilty.

Friends and supporters of the accused applaud and congratulate Tehlirian.

(The reenactment of the trial was filmed and can be viewed at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PX2L8E1PNXU)