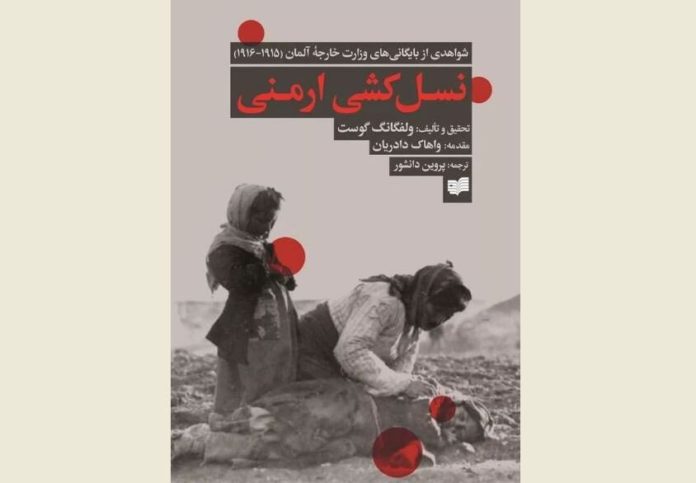

Photo: Front cover of the Persian edition of Wolfgang Gust’s book “The Armenian Genocide: Evidence from the German Foreign Office Archives, 1915-1916”. (Tehran Times photo)

Armenian Genocide Books by Gust, Kévorkian Translated into Farsi

by Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

Armenian Mirror Spectator

DECEMBER 15, 2022 — Two seminal studies of the Armenian genocide have recently appeared in Iran, in Farsi (Persian) translations. The first is Wolfgang Gust’s monumental collection of documents from the German Foreign Ministry archives, which detail what Imperial Germany knew or did not know, did or did not do, while the Young Turk regime leadership of its wartime Ottoman allies was carrying out the Genocide against the Armenians and other Christian minorities. Gust’s book, first published in German in 2005, was released in English by Berghahn in 2014, titled, The Armenian Genocide in the Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Germany in 1915-16.

Now the voluminous collection is available in Farsi, translated by Parvin Daneshvar and published by Afkar. When Tehran Times announced its appearance some months ago, it reported that, beginning in 1915, Armenians “were exiled from their land, and in the process of deportation 1.5 million of them were killed.” It went on: “The 1915-1916 annihilation of the Armenians was the archetype of modern genocide, in which a state adopts a specific scheme geared to the destruction of an identifiable group of its own citizens.”

To explain the significance of the publication, it wrote, “Official German diplomatic documents are of great importance in understanding the genocide, as only Germany had the right to report day-by-day in secret code about the ongoing genocide.” And, the Iranian daily also noted the relevance of this historic case more broadly: “The motives, methods and after-effects of the Armenian Genocide echoed strongly in subsequent cases of state-sponsored genocide.” Such publications, it went on, may function also as prevention. “Studying the factors that went into the Armenian Genocide not only gives us an understanding of historical genocide, but also provides us with crucial information for the anticipation and possible prevention of future genocides.”

Wolfgang Gust is presented as “an independent scholar based in Germany,” formerly with “the highly respected German news magazine Der Spiegel,” and author of two earlier works on the same subject as well as many articles. Not mentioned in the article is the fact that Gust has made these foreign ministry archive documents available online, in German and English, www.armenocide.net.

The second important work released in Farsi translation is The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History by French historian Raymond Kévorkian, again published by the Afkar publishing house in Tehran. As reported in Tehran Times, this volume, originally published in 2006, was translated into Persian by Saeid Karimpur.

Kévorkian’s well-known study, the newspaper explains, “provides an account of the origins, events and consequences of the years 1915 and 1916.” The author “explains and analyses the debates that occurred within the elite circles of the Young Turks, and traces the roots of the violence that would be raged upon the Ottoman Armenians.” It notes a unique aspect of the work in its “geographical account of the Armenian genocide, documenting its course region by region, including a complete account of the deportations, massacres and resistance that occurred.” Furthermore, the Iranian press review highlights Kévorkian’s depiction of “the role that the Armenian Genocide played in the construction of the Turkish nation-state and Turkish identity, exploring the ideologies of power, rule and state violence, presenting an important contribution to the understanding of how such destruction could have occurred. Beginning with an exploration of the origins of the Young Turk Revolution in 1908, Kévorkian analyses the decision-making process which led to the terrible fate of those who were deported to the concentration camps of Aleppo and along the Euphrates.”

The review notes the author’s treatment of the consequences of this genocide, in economic as well as juridical terms. The material considered in the work includes “documents from the Mazhar Governmental Commission of Inquiry and the formation of courts martial by the Ottoman authorities, and the findings of the March 1920 Committee for the Protection of the Minorities in Turkey, created by the League of Nations.”

Tehran Times does not explain the origin of such interest in the Armenian genocide, which has led to the appearance of these two books at this time. One may merely speculate. Armenia and Turkey are both neighbors of Iran in a time of extraordinary regional tensions, expressions of broader geopolitical conflict. Certainly, these books may contribute to helping Iranians understand both nations better, not only in their inter-connected history, but also in the reemergence of hostility, as manifested in Azerbaijan’s aggressions in Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, with backing from Turkey.