Rakel Dink

The Challenge of Hrant Dink’s Legacy

by Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

Armenian Mirror Spectator

COLOGNE, Germany- February 9, 2023 — A decade and a half after the assassination of Hrant Dink, the social and political injustice he fought against still reigns, not only in Turkey but also in Europe.

Xenophobic hatred and violence are being fomented by right-wing extremists, targeting newcomers, whether immigrants or refugees. Even among groups of newcomers, from Turkey, for example, there are right-wingers who have their own special targets — democratic Turks and Kurds, Armenians and increasingly, Jews. And in their homeland as well, minorities are under attack.

This was the subject of a discussion on January 21, moderated by Raffi Kantian, chairman of the German-Armenian Society (DAG), in the course of a meeting in Cologne, commemorating the anniversary of the death of Dink.

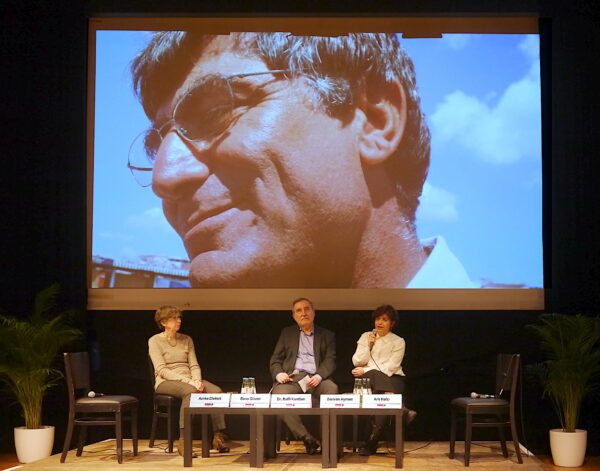

Joining the round table were Amke Dietert, Turkey expert from Amnesty International in Germany, Berivan Aymaz, Green Party politician and second vice-president of the State Legislature in North-Rhine Westphalia, and Banu Güven, a Turkish journalist and TV moderator, who has been working in Germany since 2016.

From left, Amke Dietert, Raffi Kantian and Berivan Aymaz (Photos: Klaus R. Müller, Creative Commons Lizenz)

Remembering Hrant Dink

The Agos editor’s widow, Rakel Dink, welcomed the large gathering by a video hookup. She expressed the pain of his loss, even 16 years later, recalling how Hrant in his lifetime had continued to feel the pain of the 1915 genocide. Despite extremely critical conditions in Turkey today and the continuing aggression in Nagorno-Karabakh, the situation is “not without hope,” she said, and pointed to the courageous protest movement in Iran.

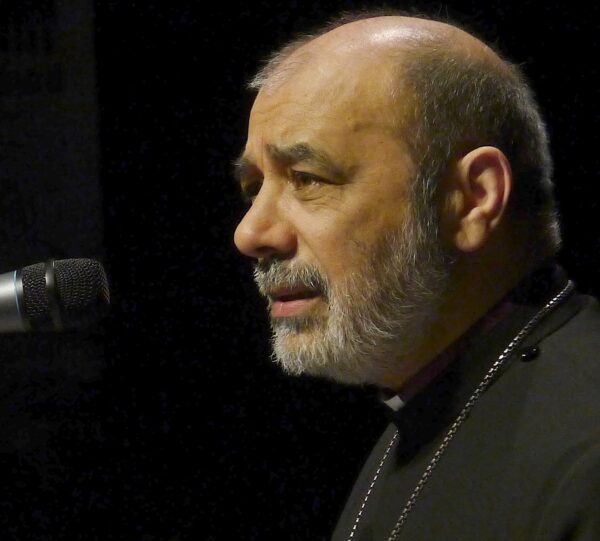

In his opening greetings, Bishop Serovpé Isakhanyan, Primate of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Germany, lamented the fact that, even 16 years later, the case of Dink’s death is still murky, and reconciliation based on justice remains distant. Reconciliation has been further undermined by the Nagorno-Karabakh war and its aftermath as well as by pervasive silence on the continuing crisis. In this connection Bishop Isakhanyan stressed the importance of “courageous voices,” like that of Hrant Dink, voices that speak out against injustice and fight for peace and reconciliation.

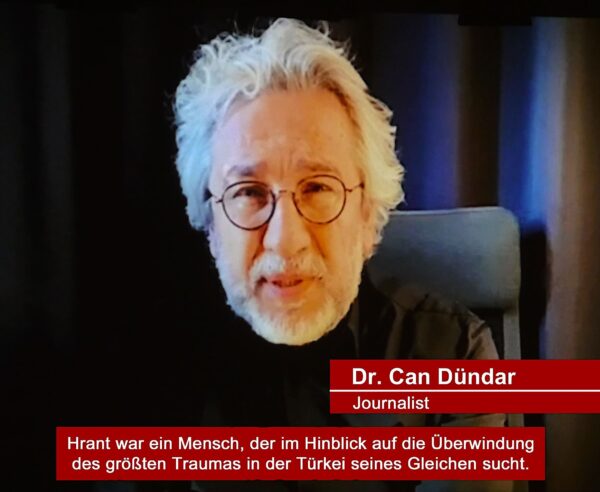

Among others, journalist Can Dündar offered brief remarks, noting two dimensions to Hrant Dink’s death. On the personal level, Dink belonged to both Armenian and Turkish society, and his death brought the two social layers together. On the political level, the case again demonstrated the problem of the untouchable State.

Can Dundar (Photos: Klaus R. Müller, Creative Commons Lizenz)

The ‘Foreigners’

The round table discussion, titled, “From Exclusion to Violence: What We Can Do Against Hate and Rightwing Extremism,” considered current events in Germany and Europe, but also in Turkey, where Istanbul mayor Ekrem Imamoglu and cultural patron Osman Kavala and their associates are facing political persecution, despite intervention by the European Court of Human Rights.

When acts of violence against foreigners occur in Germany, one often hears complaints about the “failure of integration,” a cliché implying that newcomers don’t want to be integrated — without considering whether or not it might be the integration programs that are at fault. Similarly, when a suspect is arrested for a violent act, often the first question raised in the media is the person’s ethnic identity: what is his first name?

Aymaz dubbed this pure populism, pointing out that in many cases, like the 2020 racist shooting of nine victims in Hanau, the assailants are native-born Germans. By the same token, Kantian added, there are the xenophobic foreigners, the most notorious being the Turkish terrorist organization Grey Wolves. In 2018, the Bundestag (Parliament) debated its status, and passed a resolution which, however, was watered down out of foreign policy considerations. France has forbidden the group; for Aymaz, the Grey Wolves, being the biggest extremist, racist organization in Germany, one that targets Kurds, Armenians, and Jews, can’t be allowed. The “fight against racism has priority over foreign policy issues.”

Bishop Serovpé Isakhanyan (Photos: Klaus R. Müller, Creative Commons Lizenz)

This fight, she continued, depends on resistance outside parliament, on the power of civil society. The same, Kantian noted, goes for Turkey. In this connection, attention turned to the case of Anadolu Kültür founder Osman Kavala, the reasons for his detention, and the prospects for his release. Contrary to accusations that he was behind an attempt to overthrow the government, it was his commitment to cultural pluralism that was considered a crime. Is civil society in Turkey strong enough today to mobilize, as it did following Dink’s death, when the slogan was “We are all Armenians”? For Anke Dietert, this spirit is still alive, but it faces tremendous opposition in Turkey’s nationalist, anti-minorities policy, as well as state control of the media.

Minister of Food and Agriculture Cem Ozdemir (Photos: Klaus R. Müller, Creative Commons Lizenz)

Can the upcoming elections lead to change? The fact that elections take place is itself positive, but whether they will be free and fair is an open question. Participants reported on the extreme polarization inside Turkey, as well as waning support for the ruling parties due to the economic crisis, also reflected in close poll results. At the same time, repression of any political opposition and financial constraints are hurting the opposition parties. Güven expressed concerns that this repression would increase even further, blocking funds for opposition parties. Aymaz pointed to the importance of Turkish voters living in Germany, a huge block amounting to 1.4 million people, among them ultranationalists crucial to the AKP and MHP.