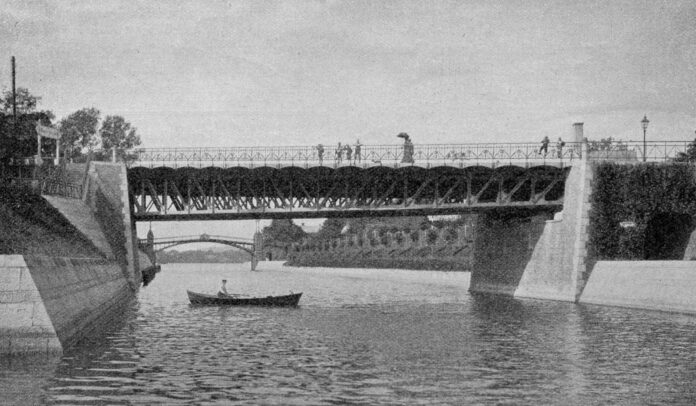

The Enver Pasha Bridge in 1906

No More ‘Enver Pasha Bridge’ in Potsdam after Complaint

by Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

the Armenian Mirror Spectator

POTSDAM, NOVEMBER 22, 2023 — Germany is known for its culture of remembrance, manifest in official acknowledgement of heinous crimes committed by previous governments in history, from the massacre of the Herero and Nama in 1904-1908 in Namibia, to complicity in the Ottoman genocide against the Armenians and other Christian minorities, to the Holocaust.

Recognition of the genocide committed by the Young Turks during World War I came only in 2016. The text of the Resolution passed by the Bundestag (Parliament) on June 2 that year clearly “deplores the deeds of the then-Young Turk government” which perpetrated the mass murders and “regrets the ignominious role of the German Empire,” which, as the Ottomans’ wartime ally, failed to intervene. The resolution furthermore stated it was the “task for education in Germany, in schools, universities, and political formation to take up study of the expulsion and extermination of the Armenians, including it in curricula and textbooks, as part of the study of the history of 20th century ethnic conflicts, to transmit this to future generations.”

How, then, could it be possible for a bridge in Potsdam, a city near Berlin, and capital of the state of Brandenburg, to carry the name of Young Turk leader Ismail Enver Pasha, wartime Minister of War and, together with Interior Minister Talaat Pasha, chief perpetrator of the genocide? One day in 2021, a local resident posed this question to a city councilwoman, whose response led ultimately to a successful initiative to remove the name.

Constituency Politics at Work

Dr. Anja Günther, a member of the Sozial.Die Linke (The Left Party) faction on the Potsdam city council, relates the story. A citizen of Potsdam was going for a walk along the Teltow Canal in late 2021, and at the location of a former bridge recognized the name “Enver Pasha” as that of a war criminal. He went to talk to his city councilor and asked if she were aware of the significance of this name. Günther is a biochemist by education and training. As a local political representative, she has dealt mainly with issues related to finance and urban development and had not been involved in remembrance culture. But, alarmed by what her constituent told her, she investigated the matter and decided to take action.

Her research on the history of the bridge revealed that it was built in 1901, named after Enver Pasha in 1915, and exploded in 1945 by soldiers of the Wehrmacht. In its place is a steel girder construction for supply lines, but the location was still known by the same name.

Anja Günther

She contacted the Waterways and Shipping Authority (WSA) for the Spree and Havel rivers, responsible for registering names, and was told to put her issue in writing and they would reply.

On January 26, 2022, Günther presented an official petition to the City Council, 22/SVV/0053, Renaming the Former Enver Pascha Bridge. In it she demanded that the City Council direct the Lord Mayor to file a motion at the WSA whereby the name of the bridge would be removed. This intervention would contribute to “overcoming, in durable fashion, the honoring of war criminals which still exists in Potsdam, for example, in street names.” At the same time, the petition calls for deleting the bridge’s name from all official documents, maps, etc.

In stating the grounds for her demand, Günther made clear her political focus. After summarizing the events leading to the current situation, she stated: “Murderers and war criminals do not deserve being named or honored in Potsdam. The namesake of the former bridge in the Potsdam district of Babelsberg, Enver Pascha, was as a politician, general, and War Minister of the Ottoman Empire (modern day Turkey) one of the people most responsible for the Armenian genocide.” Given the WSA’s declaration that the relevant authorities are open to renaming it, the petitioner proposed it be named after an anti-Nazi resistance fighter from Nowawes (as Babelsberg was previously called).

The City Council voted in favor of the motion and its cultural committee was to receive a report by March 2022.

More than a year and a half passed. Nothing happened. In September 2023 Günther presented what is called a “Small Inquiry” (Kleine Anfrage) asking what steps had been taken pursuant to the City Council’s demand. The answer given on September 5 by the Mayor’s office was that, although the decision to delete the name had been made, there had been no contact made with the WSA, because “thus far there has been no decision regarding a concrete new name.” Thus, the name remained on site and in the records and would remain until a new name were decided. Günther also inquired whether there had been any protest or intervention of the side of Turkish interests, but the answer was negative.

The idea was that a new name depended on a new bridge. Günther objected and was quoted in the press saying, “perhaps one might keep the name of a bridge that no longer exists until a new one is built, but not when the name is that of a war criminal and genocidal murderer.” Her party colleague Sascha Krämer accused the Town Hall of “hair-splitting;” if a decision had been made, that meant it should be implemented, and a simple letter to the WSA should be sufficient. Günther contacted the WSA and presented an argument she thought might conform to their line of reasoning: If there can be no new name without a new bridge, then there should be no old name for the old bridge, because it is no longer there. You can delete the old name now and assign a new one when the new construction is completed. The official at the WSA was satisfied.

Roy Knocke (Fotostudi-Neukoelln)

Finally, in mid-October, an Official Notice signed by the Lord Mayor was released. It stated, the name “Enver Pasha Bridge” will be “officially retracted and deleted from the street directory.” The reason given for the decision is not political, and its formulation reflects the Aristotelian logic that Günther had suggested. It reads: “The original bridge was blown up in April 1945 and as a result is no longer there. The construction currently associated with this name is a 1970s-erected electrical supply line on steel girders, which however has no transport function. Since the actual bridge therefore no longer exists and the current supply bridge requires no name, the name still partially being used is groundless and nonfunctional…. [Therefore] it clearly must be revoked and deleted from all official directories.” In a departure from normal procedure, the declaration makes absolutely no mention of the City Council’s resolution which was the basis for the administration’s decision, nor of its motivation – a fact that Günther finds “scandalous.” The official announcement is duly signed by Lord Mayor Mike Schubert (SPD).

Günther pursued the issue further, demanding that the name be removed also from Google maps and all other representations of the location. Discussion then focused on the name to be given a future bridge.

Enver Pasha in Potsdam

One might wonder what the Ottoman War Minister had to do with Potsdam in the first place. Roy Knocke, director of the Lepsius House in Potsdam, gave some background to the matter in an interview published September 21, 2023 in the Märkische Allgemeine Zeitung. Enver had served as military attaché from 1909 to 1912 in the capital of the Brandenburg province of the German Empire. Fluent in German, Enver was, in Knocke’s characterization, “a kind of Ottoman superstar in Imperial Germany,” or a “poster boy for the German-Ottoman friendship,” whose center was in the Babelsberg area where the bridge was located. There was even a big tobacco factory in Berlin named after Enver at the time. That the name should be deleted is “an imperative” for Knocke, in the interests of a true culture of remembrance. In 2000, discussion had begun around a new name, and of course, that of Johannes Lepsius was suggested. Lepsius, Knocke recalled, had fought against repression of the Armenians already during the 1890s Hamidian massacres and, in 1915/16 in Potsdam, compiled his documentation of the genocide committed by the Young Turk regime. He distributed the work widely but failed to shift Imperial Germany’s policy, due to the wartime alliance.

Andreas Fritsche, writing in nd-aktuell on November 11, noted that right after the armistice in 1918, Enver was among a group of Young Turk perpetrators who escaped aboard a German submarine, thanks to General Hans von Seeckt, one of their close allies. They made it to Berlin, where they lived in comfortable exile under assumed names. Interior Minister Talaat Pasha was shot dead in Berlin by a member of the Nemesis group, Soghomon Tehlirian in 1921, whereas Enver traveled to the Caucasus to lead a military campaign to establish a “pan-Turanian” empire, and was killed in 1922.

A new bridge was supposed to be built but the East German Communist regime put up the notorious wall dividing Berlin in 1961, and that nullified construction plans. Although the Berlin Wall came down in November 1989, no new bridge has replaced it. There is talk of construction in 2027. And therefore, of a new name. Knocke and Günther have initiated discussion, and proposed, in addition to Lepsius, the name of an anti-Nazi resistance fighter from the area. What is important, Günther stresses, is that the location be identified as a place of remembrance.

Remembrance or Denial

Removal of this mass murderer’s name is a victory (notwithstanding the curious nature of the WSA’s linguistic acrobatics), one that its political initiator Anja Günther and those supporting her motion in the Social Democratic (SPD), Green (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen), and Left parties can be proud of. But more remains to be done in the interest of remembrance.

Not far from Potsdam, in the federal capital Berlin, is a cemetery where other Young Turk perpetrators lie in honored graves. They are Bahaeddin Sakir, leader of the Special Organization, and Cemal Asmi Bey, known as the “Butcher of Trebizond.” Both had been condemned to death by the Constantinople trials, in absentia; they had escaped on board the same ship as Enver, and lived under assumed names in Berlin. Members of Nemesis killed them together on April 17, 1922. Their graves, richly renovated in 2011, are in the Sehitlik (Martyrs’) Cemetery (formerly Islamic Cemetery). Interior Minister Talaat Pasha had also been buried there until the Nazi regime returned his remains to Turkey in 1943. Any attempt to alter their location or status would be in vain, given that the cemetery is sovereign Turkish territory, purchased in 1921 and administered by the Turkish Defense Ministry.

Against this background, it is understandable that in her formal inquiry regarding implementation of the decision to remove Enver Pasha’s name, Anja Günther asked whether there had been Turkish intervention. As journalist Fritsche recalled in his article, Turkish influence had previously censored references to the Armenian genocide. He writes that in 2005, Matthias Platzeck (SPD), while governor of Brandenburg, had dinner with the then-Turkish Consul General Aydin Durusay, following which “the Armenian genocide disappeared from the syllabus and course plan for history classes in the federal state of Brandenburg.” There followed protests by Armenians, historians, and political figures; in the end a pledge was made to include it, along with other examples of genocide.