History Is Not Capricious:

Exploring Root Causes

by Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

the Armenian Mirror Spectator

OCTOBER 24, 2024 – The anniversary of the expulsion of Armenians from Artsakh just weeks ago was met with sadness and mourning, political disputes, and attempts to identify those to blame for the catastrophe. It was also a time for reflection, and searching for the deeper causes behind developments. On this anniversary, a new book appeared, both in Germany and Norway, which offers a serious approach to finding answers to these questions.

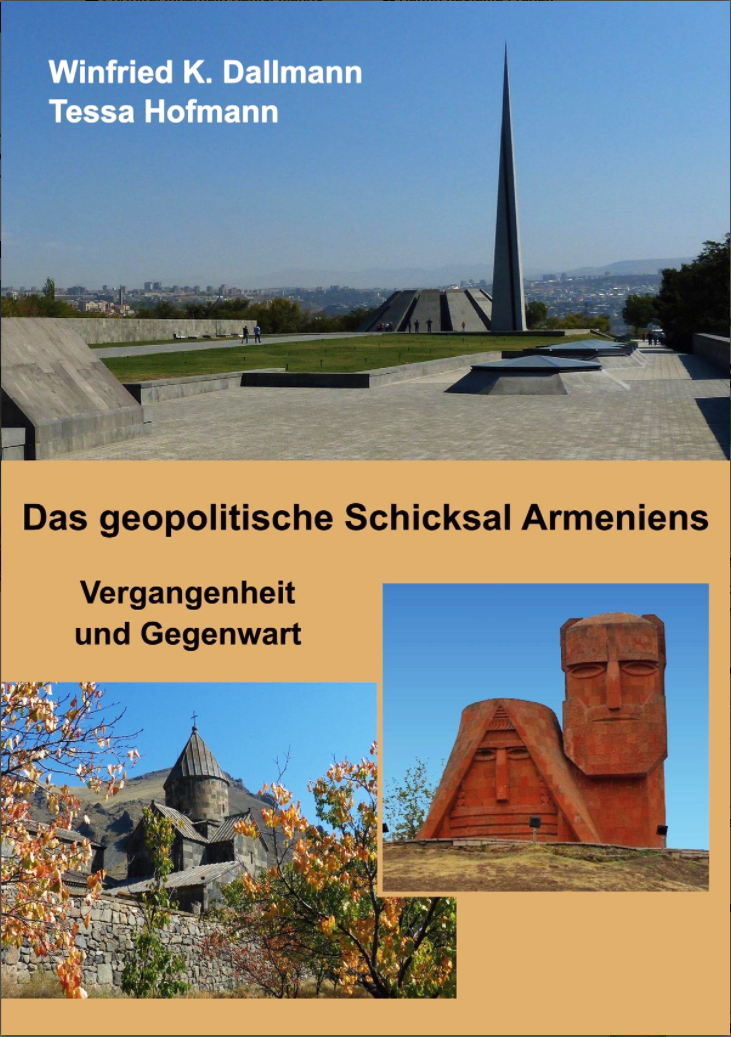

Entitled, Das geopolitische Schicksal Armeniens:Vergangenheit und Gegenwart (Armenian’s Geopolitical Fate: Past and Present), the book is the result of a collaborative effort by Norwegian geologist and ethnologist Winfried K. Dallmann and German sociologist, genocide researcher and human rights proponent Tessa Hofmann. In their foreword, they state bluntly that, in answer to the search for the “causes, the development, and above all the possible ways out” of the crisis, both political analysts and mass media have failed to be measured or objective. With their book they seek to provide an alternative.

Although since August 2022 several authoritative institutional voices, like the Lemkin Institute for Genocide Prevention, the International Association of Genocide Scholars and former International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo, have explicitly warned of genocide in the Azerbaijani aggression and expulsion of the Artsakh Armenians, in the western media the echo has been faint. Perhaps with the world focus on the Ukraine-Russia war, Armenia, close to the latter, is considered “on the wrong side” — despite the shifts in Russian President Vladimir Putin’s own posture towards Armenia and Azerbaijan, claiming strategic partnership with both.

This makes the point, which is the thrust of the book, that this crisis can only be understood in terms of geopolitics; not in the short term, but rather from the earliest times. The authors explore the historical background in the 11th century invasion of Turkic peoples in the Caucasus and discuss Armenia under successive foreign empires, its independence as a kingdom, further subjugation, up to the Ottoman and Iranian dynasties. Following treatment of Russia and Armenia from 1828 to 1914, they move to 20th century Ottoman empire, with the incisive chapter devoted to World War I and the genocide. “But, not only,” they write; in the Soviet period too, Armenia’s elites were subjected to the “great cleansing” of 1936-39, From this standpoint, what the post-Soviet Azerbaijan regime is engaged in must be seen as a “genocidal depopulation, supported by its ‘brotherly’ Turkish people, the remains of the once 300,000 square kilometer Armenian highlands.” The name of the campaign is ”Pan-Turkism.”

While documenting their historical excursus, the authors attack the reign of “fake news” as well as more subtle means of compromising historical truth. Whereas autocratic regimes cheerfully deploy lying coverage, press organs in democratic nations may simply ignore political realities or engage in “false balance” or “both-sidesism” or “whataboutism,” whereby controversial themes are treated as if victim and perpetrator were on an equal plane. This produces erroneous judgments and privileges the aggressor. Such manipulation generates what the authors call “geopolitically motivated double standards.”

Taking the Russia-Ukraine conflict as an example, the authors note the facility with which mass media may condemn any analyst who seeks root causes behind the conflict, as a “Putin-Versteher” — someone who “understands” Putin, instead of denouncing him. With reference to the second Karabakh war in 2020, mass media tended to argue that “both sides accuse the other of starting the conflict, both sides are called upon to come to reason,” etc. Double standards reign in the sanctions policy of the European Union, which has refused to stop importing gas from Azerbaijan, as well as in the interpretation of sovereignty according to international law. Here, Stalin’s arbitrary territorial decisions on Karabakh win legitimacy; Kosovo is granted self-determination, but Karabakh not.

The hefty volume — 450 pages long and richly illustrated with maps — documents the historical process culminating in the Karabakh catastrophe. More than half the book deals with the Republic of Armenia and the Karabakh conflict, from 1991 to the present. Having provided a substantial overview of a history stretching back to Urartu, the authors demonstrate the importance of the geopolitical dynamic governing the entire process and conclude with consideration of new aspects in the peace negotiations between Yerevan and Baku.