Creating a Transnational Memory Space Dogan Akhanli Honored in Cologne

Sep/27/2014 Archived in:Armenian Genocide

By Muriel Mirak-Weissbach – Special to the Mirror-Spectator

COLOGNE, Germany — If post-war Germany was able to acknowledge the Holocaust and work through its implications, politically and psychologically, why cannot the present Turkish establishment do the same regarding the 1915 Genocide? It is not only Armenians in and outside Germany who raise this question, but also Germans of Turkish descent, first among them Dogan Akhanli, who received the Georg Fritze Memorial Award in Cologne, Germany on September 19. The festive ceremony took place in the Kartäuserkirche (Carthusian Church), where Georg Fritze (1874-1939), in whose memory the prize was established, served. In his opening remarks, Superintendent Rolf Domning, the current Protestant pastor and regional church leader, greeted the large audience, which included representatives of several faiths, political and civil society figures as well as a descendant of Fritze. Quoting the passage in Chronicles, “Be not afraid...,” he honored the Protestant theologian and activist who “had the courage to oppose dictatorship and violence” in the Nazi period. Akhanli, he said, has shown in his person and works similar courage, especially in his recognition of the Genocide against the Armenians. Cologne’s Mayor Jürgen Roters characterized Akhanli as a man with “a great passion for human rights.”

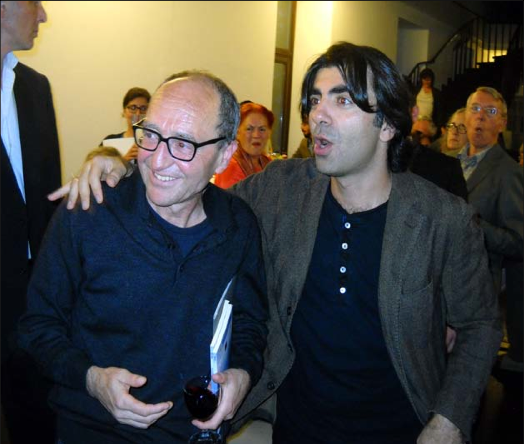

Most appropriately, it was Fatih Akin, the Turkish-German filmmaker whose latest work “The Cut” deals with the Genocide, who was invited to deliver the laudatio, a speech in honor of Akhanli. He began by characterizing Fritze as a “traitor to his fatherland” and one who scorned power, — “that is, a good man,” and used the same terms to describe Akhanli. When novelist Akhanli designated the mass murder of Armenians in 1915 a genocide, “those in power in Turkey shouted out ‘A traitor to the fatherland!’ and threw him in prison in 2010.” In fact, Akhanli “was the first Turkish writer to report on the Armenian Genocide,” he stressed. And his novel, The Judges of the Last Judgment, which appeared in 1999 in Turkey and 2007 in a German translation, provoked such rethinking and self-questioning, that he “was declared persona non grata in his native country.”

Akin described how Akhanli, whom he met a year ago in Hamburg, had conducted seminars and trips to sites commemorating the victims of violence and genocide, during which participants, whether German, Armenian, Turkish, Kurdish or Jewish, could “work through their intertwined histories with respect.” He emphasized that, to “achieve a clear vision of the crimes against the Armenians,” Akhanli had to “fight his way through the forest of lies of Turkish historiography,” and that included wresting with “the indifference of the Turkish leftists” who “themselves had grown up in the Turkish lying to themselves.” What makes Akhanli’s educational activities so convincing is the fact that he too has been victimized by brutality and violence, but has not responded with violence. “People like him,” Akin stated, “ ... can tolerate the pain because in dealing with the injustice they themselves have experienced and that others have had to endure, they display care and sensitivity.”

Akin described how Akhanli, whom he met a year ago in Hamburg, had conducted seminars and trips to sites commemorating the victims of violence and genocide, during which participants, whether German, Armenian, Turkish, Kurdish or Jewish, could “work through their intertwined histories with respect.” He emphasized that, to “achieve a clear vision of the crimes against the Armenians,” Akhanli had to “fight his way through the forest of lies of Turkish historiography,” and that included wresting with “the indifference of the Turkish leftists” who “themselves had grown up in the Turkish lying to themselves.” What makes Akhanli’s educational activities so convincing is the fact that he too has been victimized by brutality and violence, but has not responded with violence. “People like him,” Akin stated, “ ... can tolerate the pain because in dealing with the injustice they themselves have experienced and that others have had to endure, they display care and sensitivity.”

Akin described the impact that Akhanli’s drama, “Anne’s Silence,” has had, a story of a Turkish girl raised in Germany who learns after her mother’s death that she was Armenian. This piece, he said, “is like a metaphor” for all sides, not only a personal, individual story, but one that has mass dimensions, something Akin himself experienced when dealing with the Genocide. “Dogan Akhanli,” he concluded, “has encouraged many to follow this path. He has thus started a social discourse and made healing possible, even between victims and perpetrators.”

Following the official delivery of the prize, accompanied by loud cheers and clapping, Akhanli delivered his remarks. In a speech entitled, “We Need a Transnational Memory Space,” he presented the process through which he came to develop an understanding of the relationship between the Holocaust and the Genocide. But first, he delivered his thanks to many associates, several of whom were present. First was his “friend and mentor, Albrecht Kieser,” who coordinated the campaign for his release from his “Kafkaesque imprisonment in 2010,” as well as the many supporters who participated in the mobilization. Akhanli dedicated his speech to two individuals no longer alive. One was Adnan Keskin, a childhood friend with whom he began political activity in Turkey, and who, like himself, was twice jailed. Keskin managed to escape by digging a tunnel with his own hands, and reached Germany in 1987, then four years later facilitated Akhanli’s own escape and flight to German exile. Keskin was a co-founder of the Turkish human rights association Tüday in Cologne, and in 2007 joined Akhanli to establish the Raphael Lemkin Library in the same city. The other person was a woman

Akhanli never met, but learned about in a film by Eric Friedler (the man who produced “Aghet”). Her name was Elisabeth Käsemann, a German who, while providing support for the poverty stricken in Argentina was arrested by the military regime, jailed, tortured and killed. Akhanli cited her case, because she had been left in the lurch by German authorities, despite public protests. He, on the other hand, was not left in the lurch; during his 2010 imprisonment, in fact, the German consul even visited him in prison and brought him German language magazines, books and newspapers. “During my sleepless nights in my cell,” he said, “I was therefore able to take refuge in the German language, which I had learned as a foreign language after my flight to Cologne in the 1990s. It was a bitter experience,” he went on, “to experience how my mother tongue, which is also my professional or artistic language, in the mouths [between the teeth?] of the prosecuting attorneys, judges, police and prison guards became a foreign language for me.” He expressed his gratitude also to the numerous German politicians, including Cologne’s Lord Mayor, who had intervened on his behalf, and reported that his defense attorney “almost fainted from joy, when he reported to me during a visit that Christians had prayed for me” in a local church.

Although in prison he enjoyed certain privileges, he witnessed the misery and solitude reserved for the Kurds, whose imprisonment he characterized as “the last stage in the national project of the Young Turks, that was constructed over 100 years ago.” He explained: “The Turkish national project, which in the words of today’s Turkish President Erdogan is updated as ‘One nation, one flag, one religion!’, drove the elimination of the Armenians and the

Arameans, the killing and expulsion of the Pontus Greeks, the massacre of the Dersim Kurds and Alevites and the emigration of ninety per cent of the Turkish Jews. The denial of Kurdish identity is no coincidence, but the continuation of the national project, which has sacrificed and demanded hundreds of thousands of victims and which is condemned to failure.”

His own good fortune did not begin with his release in 2010, he said. He had survived “the 1970s civil war and the 1980s military coup, the underground and military prison.” With his wife and son, he also survived torture: “I am grateful to my former wife Ayse,”—present at the ceremony – “who went through hell with me,” he said. “If I did not come out of the torture chamber a broken man, it is thanks to her courage and resistance.”

It was in Cologne that Akhanli began his writing, and writing “completely changed my life,” he said. “I turned from a convinced activist who thought he knew all about the world into a person who had more questions than answers.” He discovered the link between what he and his family had endured and the “historical violence” in his native country, and asked what it had to do with the Genocide. In this connection, the way the Germans worked through their own historical past helped him work through the history of his own country. After completing his novel, it was clear to him that “the Genocide victims of 1915 were subjugated to the absolute, total despotism of Young Turk power. They had been collectively condemned to death.” Akhanli expressed his thanks that the “community of Armenian survivors” had not rejected his book.

His experience with Germany’s approach to the Holocaust helped him understand the issue of identity as well. After his daughter, raised in Germany, was shocked by a film about the Holocaust, she reacted by wanting to shed her German identity. Akhanli asked himself, “What will happen if I tell my children about the Armenian Genocide, what identity can they flee to?” This led him to seek a way to tell both stories in such a manner as to make clear that “The Holocaust is not only a German-Jewish history, it is an international story.” For this reason he started touring Germany and all its memorial sites, reading books and watching films about the Holocaust. A visit to Auschwitz was traumatic for him, he felt that “victim and perpetrator were melded together” in himself, and this experience led him to redefine his life’s task.

Quoting Walter Benjamin’s notion that the past can be changed, Akhanli said he understood this not as undoing the deeds of the past, but as “changing the meaning of the past” and writing the history of the victims anew. Here, in the case of 1915, he said Lemkin had given it a name and historians had documented that and subsequent genocides; yet “Turkish policy wants to erase the past and pursue its murderous national state project, in order to rob the future of its memory and thus destroy it.” Pointing to the documented facts about German complicity in the Genocide, Akhanli raised the question why, having drawn the lessons from its own history, German foreign policy does not intervene in defense of human rights in Turkey and why educational policy does not see the need to deepen knowledge of Germany’s complicity. Why shouldn’t this be part of education on the Holocaust? This, he said, would not mean relativizing the Shoah or diminishing its significance, but would be a way of expanding and deepening the process of working through the German experience, “which should no longer remain German. In order to shape the future,” he said, “we need a transnational memory space. Here and everywhere.”

In conclusion, he thanked Akin, whose film “The Cut,” has created such a “transnational memory space.” “It is a courageous idea, a great idea of yours,” he said, addressing Akin, “to have the film begin in 1915 and end in 1923. In choosing this time frame you have placed in question the founding myths of the Turkish Republic. It is glorious that with your leading character, who was put to silence through violence, you have broken the global silence and given back to the Genocide victims their voices.

COLOGNE, Germany — If post-war Germany was able to acknowledge the Holocaust and work through its implications, politically and psychologically, why cannot the present Turkish establishment do the same regarding the 1915 Genocide? It is not only Armenians in and outside Germany who raise this question, but also Germans of Turkish descent, first among them Dogan Akhanli, who received the Georg Fritze Memorial Award in Cologne, Germany on September 19. The festive ceremony took place in the Kartäuserkirche (Carthusian Church), where Georg Fritze (1874-1939), in whose memory the prize was established, served. In his opening remarks, Superintendent Rolf Domning, the current Protestant pastor and regional church leader, greeted the large audience, which included representatives of several faiths, political and civil society figures as well as a descendant of Fritze. Quoting the passage in Chronicles, “Be not afraid...,” he honored the Protestant theologian and activist who “had the courage to oppose dictatorship and violence” in the Nazi period. Akhanli, he said, has shown in his person and works similar courage, especially in his recognition of the Genocide against the Armenians. Cologne’s Mayor Jürgen Roters characterized Akhanli as a man with “a great passion for human rights.”

Most appropriately, it was Fatih Akin, the Turkish-German filmmaker whose latest work “The Cut” deals with the Genocide, who was invited to deliver the laudatio, a speech in honor of Akhanli. He began by characterizing Fritze as a “traitor to his fatherland” and one who scorned power, — “that is, a good man,” and used the same terms to describe Akhanli. When novelist Akhanli designated the mass murder of Armenians in 1915 a genocide, “those in power in Turkey shouted out ‘A traitor to the fatherland!’ and threw him in prison in 2010.” In fact, Akhanli “was the first Turkish writer to report on the Armenian Genocide,” he stressed. And his novel, The Judges of the Last Judgment, which appeared in 1999 in Turkey and 2007 in a German translation, provoked such rethinking and self-questioning, that he “was declared persona non grata in his native country.”

Akin described the impact that Akhanli’s drama, “Anne’s Silence,” has had, a story of a Turkish girl raised in Germany who learns after her mother’s death that she was Armenian. This piece, he said, “is like a metaphor” for all sides, not only a personal, individual story, but one that has mass dimensions, something Akin himself experienced when dealing with the Genocide. “Dogan Akhanli,” he concluded, “has encouraged many to follow this path. He has thus started a social discourse and made healing possible, even between victims and perpetrators.”

Following the official delivery of the prize, accompanied by loud cheers and clapping, Akhanli delivered his remarks. In a speech entitled, “We Need a Transnational Memory Space,” he presented the process through which he came to develop an understanding of the relationship between the Holocaust and the Genocide. But first, he delivered his thanks to many associates, several of whom were present. First was his “friend and mentor, Albrecht Kieser,” who coordinated the campaign for his release from his “Kafkaesque imprisonment in 2010,” as well as the many supporters who participated in the mobilization. Akhanli dedicated his speech to two individuals no longer alive. One was Adnan Keskin, a childhood friend with whom he began political activity in Turkey, and who, like himself, was twice jailed. Keskin managed to escape by digging a tunnel with his own hands, and reached Germany in 1987, then four years later facilitated Akhanli’s own escape and flight to German exile. Keskin was a co-founder of the Turkish human rights association Tüday in Cologne, and in 2007 joined Akhanli to establish the Raphael Lemkin Library in the same city. The other person was a woman

Akhanli never met, but learned about in a film by Eric Friedler (the man who produced “Aghet”). Her name was Elisabeth Käsemann, a German who, while providing support for the poverty stricken in Argentina was arrested by the military regime, jailed, tortured and killed. Akhanli cited her case, because she had been left in the lurch by German authorities, despite public protests. He, on the other hand, was not left in the lurch; during his 2010 imprisonment, in fact, the German consul even visited him in prison and brought him German language magazines, books and newspapers. “During my sleepless nights in my cell,” he said, “I was therefore able to take refuge in the German language, which I had learned as a foreign language after my flight to Cologne in the 1990s. It was a bitter experience,” he went on, “to experience how my mother tongue, which is also my professional or artistic language, in the mouths [between the teeth?] of the prosecuting attorneys, judges, police and prison guards became a foreign language for me.” He expressed his gratitude also to the numerous German politicians, including Cologne’s Lord Mayor, who had intervened on his behalf, and reported that his defense attorney “almost fainted from joy, when he reported to me during a visit that Christians had prayed for me” in a local church.

Although in prison he enjoyed certain privileges, he witnessed the misery and solitude reserved for the Kurds, whose imprisonment he characterized as “the last stage in the national project of the Young Turks, that was constructed over 100 years ago.” He explained: “The Turkish national project, which in the words of today’s Turkish President Erdogan is updated as ‘One nation, one flag, one religion!’, drove the elimination of the Armenians and the

Arameans, the killing and expulsion of the Pontus Greeks, the massacre of the Dersim Kurds and Alevites and the emigration of ninety per cent of the Turkish Jews. The denial of Kurdish identity is no coincidence, but the continuation of the national project, which has sacrificed and demanded hundreds of thousands of victims and which is condemned to failure.”

His own good fortune did not begin with his release in 2010, he said. He had survived “the 1970s civil war and the 1980s military coup, the underground and military prison.” With his wife and son, he also survived torture: “I am grateful to my former wife Ayse,”—present at the ceremony – “who went through hell with me,” he said. “If I did not come out of the torture chamber a broken man, it is thanks to her courage and resistance.”

It was in Cologne that Akhanli began his writing, and writing “completely changed my life,” he said. “I turned from a convinced activist who thought he knew all about the world into a person who had more questions than answers.” He discovered the link between what he and his family had endured and the “historical violence” in his native country, and asked what it had to do with the Genocide. In this connection, the way the Germans worked through their own historical past helped him work through the history of his own country. After completing his novel, it was clear to him that “the Genocide victims of 1915 were subjugated to the absolute, total despotism of Young Turk power. They had been collectively condemned to death.” Akhanli expressed his thanks that the “community of Armenian survivors” had not rejected his book.

His experience with Germany’s approach to the Holocaust helped him understand the issue of identity as well. After his daughter, raised in Germany, was shocked by a film about the Holocaust, she reacted by wanting to shed her German identity. Akhanli asked himself, “What will happen if I tell my children about the Armenian Genocide, what identity can they flee to?” This led him to seek a way to tell both stories in such a manner as to make clear that “The Holocaust is not only a German-Jewish history, it is an international story.” For this reason he started touring Germany and all its memorial sites, reading books and watching films about the Holocaust. A visit to Auschwitz was traumatic for him, he felt that “victim and perpetrator were melded together” in himself, and this experience led him to redefine his life’s task.

Quoting Walter Benjamin’s notion that the past can be changed, Akhanli said he understood this not as undoing the deeds of the past, but as “changing the meaning of the past” and writing the history of the victims anew. Here, in the case of 1915, he said Lemkin had given it a name and historians had documented that and subsequent genocides; yet “Turkish policy wants to erase the past and pursue its murderous national state project, in order to rob the future of its memory and thus destroy it.” Pointing to the documented facts about German complicity in the Genocide, Akhanli raised the question why, having drawn the lessons from its own history, German foreign policy does not intervene in defense of human rights in Turkey and why educational policy does not see the need to deepen knowledge of Germany’s complicity. Why shouldn’t this be part of education on the Holocaust? This, he said, would not mean relativizing the Shoah or diminishing its significance, but would be a way of expanding and deepening the process of working through the German experience, “which should no longer remain German. In order to shape the future,” he said, “we need a transnational memory space. Here and everywhere.”

In conclusion, he thanked Akin, whose film “The Cut,” has created such a “transnational memory space.” “It is a courageous idea, a great idea of yours,” he said, addressing Akin, “to have the film begin in 1915 and end in 1923. In choosing this time frame you have placed in question the founding myths of the Turkish Republic. It is glorious that with your leading character, who was put to silence through violence, you have broken the global silence and given back to the Genocide victims their voices.