Armenian Architecture and Genocide

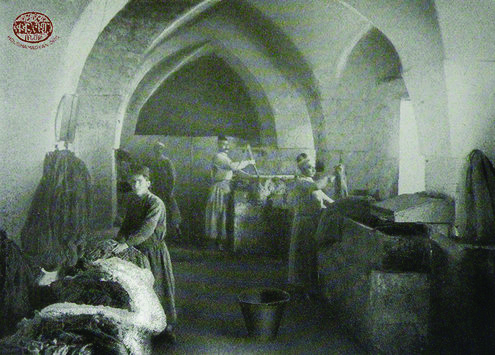

Armenian workers in Urfa (Source: Paul Rohrbach, Armenia , Stuttgart, 1919; photo courtesy of Houshamadyan)

by Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

OSNABRÜCK, Germany, January 2, 2020 — The aim of the Young Turk leaders in organizing the genocide was to rid the country of the Armenians, as a population and a culture. They determined to “Turkify” the land, cleanse it ethnically of the Christian minorities, and erase, to the extent possible, all traces of their existence. Among the myths created at the time of the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923, was the tale that the Armenians had not inhabited those lands; they had “always been Turkish.”

In 2011, I had the opportunity to travel with my brother and my husband to Turkey, as part of a group of Armenians from America. Our guide was the indefatigable Armen Aroyan of California, who has accompanied groups of “pilgrims” to the lands of historic Western Armenia for over a quarter century. We were hoping to rediscover the villages where our parents had lived, in the Arapkir province, and were fortunate enough to find them. But signs of Armenian life were nowhere to be found. In other cities and towns we visited, like Kars, we found the remains of Armenian churches turned into mosques; in other localities they had become museums, still others, stables where animals lived.

Yet, the evidence of Armenian life and culture could not be totally eradicated; the very stones, albeit in ruins, could bear testimony to the story of the people who once lived there, with their homes, their shops and factories, their schools and churches—above all, churches, chapels and monasteries. Ani, the ancient capital of an Armenian kingdom, with its legendary 1001 churches, is the most eloquent example. What was most painful, as I wrote in a report on our visit, was to witness the attempt to eradicate memory itself. (See https://mirrorspectator.com/2011/07/29/opinion-the-stones-will-cry-out/)

A Story of Cultural Genocide

Now Germans have the opportunity to make a similar journey through parts of historic Armenia, albeit not in person, but through images and words. On December 5, an exhibition opened in Osnabrück, which documents precisely this history. “1915-2015. Armenische Architektur und Genozid” is the title of the exhibition organized by the Erich Maria Remarque-Friedenszentrum (Peace Center) in cooperation with the German-Armenian Society (DAG). The venue of the show is particularly significant. The Erich Maria Remarque Peace Center, founded in 1996 by the city and university of Osnabrück, is dedicated to the life and works of the author best known for his “All Quiet on the Western Front.” The center has an archive open to researchers, and organizes regular activities including exhibitions, lectures, film showings and symposia. Among them have been two events on Armin T. Wegner. For Dr. Raffi Kantian, president of the DAG, it is especially appropriate to hold the exhibition at this center; he stressed that whereas Remarque in his world famous book, “described the horrors of World War I on the Western front,” the exhibition presents the “consequences of the extermination of the Armenians on the Eastern front.”

After greetings by Dr. Thomas F. Schneider, from the Osnabrück University and an opening address by Mayor Birgit Strangmann, Dr. Kantian introduced the large audience to the events of 1915 and the theme of the exhibition, which will run until January 19, 2020.

The question that the display poses and seeks to illustrate, is: “What impact has the genocide had on the cultural legacy of the Armenians in Turkey?” Twenty-two huge panels (six-feet high) present in text and photographs the main stations in the drama: first, Armenian life before 1915 is depicted, in its multifaceted forms, through family photos, as well as scenes of towns and cities where Armenians lived and worked, studied and prayed. Accompanying the pictures are texts providing background information for visitors who may be unfamiliar with the subject.

The deportations and massacres are illustrated, with explanatory texts based on accounts by American Ambassador Henry Morgenthau and survivor Pailadzo Captanian. The next section depicts the “Destruction of Armenian Lebensraum,” literally, the elimination of the physical basis for continued existence. Here, as we saw on our travels through eastern Turkey in 2011, entire communities were wiped out, and with them, all the physical structures, whether homes or workplaces, buildings for manufacture or commerce, and, of course, the schools and places of worship. “Before” and “After” photos of the same location, for example in Sivas, show the complete replacement of Armenian architecture by modern shopping centers.

Johannes Lepsius (Photo courtesy of Wikipedia)

The fate of the cloisters and churches deserves special treatment. Here the panels show historic photographs of the majestic churches before and after the destruction, Surp Garabed in Mush, for example. The image that symbolizes the tragedy and stands as emblematic for the entire exhibition, is a 1900 photograph of the magnificent Khtzkonk monastery, a complex of five edifices in Tekor, which was blown up in 1964, leaving one lonely church standing in ruins against a devastated landscape. Other monasteries, a handout for the exhibition explains, “were razed (Karmravor Monastery Surp Asdvadsadsin), destroyed and used as building material for houses and mosques (Surp Garabed in Mush).” Worse still, some churches were degraded to function as barns, stalls, storage rooms or even prisons.

The exhibition highlights the Mush-Sasun-Van region for the important role it plays in Armenian history. As early as the fifth century, monasteries were vibrant centers of cultural activity, which produced valuable manuscripts and miniatures; literary and spiritual life flourished in the region which boasted up to 250 churches, cloisters (as on the island of Lim) and fortresses among other architectural monuments. One exception to the rule of destruction is the Surp Khach on the island of Achtamar, a jewel of Armenian church architecture which has escaped ruin and even been renovated. Though reclassified as a museum and allowed only one church service a year, this majestic structure, with its unique bas relief sculptures, is a treasure to behold.

Although many cities through the genocide were deprived of their Armenian character, some, like Sivas, managed to maintain traces of community life. Here, the exhibition presents the example of the Shahinyan family as testimony to the city’s history. The respected family hails from a member of the first Ottoman parliament in 1877, Agop Shahinyan; many photographs record images of his family and their home (built in 1877), officially recognized as an outstanding example of Ottoman architecture – without mention of its Armenian origins.

What’s In a Name?

It was a deliberate policy, pursued by the Turkish authorities since the genocide, to eradicate the Armenian identity of the land, its history and its culture, as embodied in its architecture. Thus, the very name “Armenian” was erased from written records, whether they be texts for school children or place names in geographical locations or maps. In Kars or Ani, if reference is made to the Bagratids, there is no hint that the name might refer to Armenians.

Urfa is yet another example of a city deprived of its people and identity. Once it was home to 38,000 Armenians before the genocide; skilled craftsmen who worked as goldsmiths and carpet weavers, they lived in a community with functioning schools and an active Protestant parish. During the Hamidian massacres, 3,000 Armenians who had sought refuge in their church, were burned to death in the Surp Asdvadsadsin. This was the city where the German humanitarian and pastor Johannes Lepsius set up his rug factory, to provide refuge and employment to Armenian orphans. Today, one learns at the exhibition, the location hosts a hotel.

This important and timely exhibition was made possible through the efforts of many persons and institutions, among them, the Armenische Unternehmerverband e.V., Hasmik Hagopian, the two sponsoring associations, and a long list of individuals and organizations, which made the photographic material available.

(Material for this article has been taken from an article by Giorgio Bavaj and Alfrant Bedrosian, “1915-2015. Armenische Architektur und Genozid. Eine Ausstellung.” The article, which is a handout for the exhibition, has been published on the website www.remarque.uni-osnabrueck.de/aktuell.html).