Symposium: Life After Babylon

Mar/21/2019 Archived in:Culture | Armenian Genocide

by Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

HANNOVER, Germany, MARCH 14, 2019 — People of Jewish or Armenian heritage know that they share a painful history, one that deprived them of statehood and forced them into life in the diaspora over centuries.

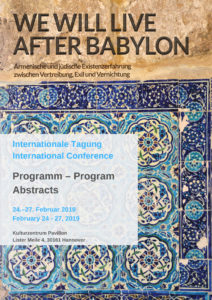

In view of this shared, but differentiated experience, the European Center for Jewish Music (EZJM) and the German-Armenian Society (DAG) joined to organized a symposium at the Cultural Center in Hannover, from February 24-27.

Titled “We Will Live After Babylon: Armenian and Jewish Historical Experience between Expulsion, Exile and Destruction,” the three-day conference presented a vast spectrum, highlighting the diversity as well as the similarities in their historical experience. Scholars from all over the world joined in panels to exchange views on diaspora and minority issues, the Genocide and Holocaust as a breach of civilization, their commemoration and reception, and the relationship between the two communities today.

Between Annihilation, Dispersion and Revival

Following welcoming remarks on behalf of the sponsoring organizations by Prof. Sarah Ross (EZJM) and Dr. Raffi Kantian (DAG), historian Dan Diner from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem delivered the keynote on Imperial Remnants: Minority, Nation-State and Genocide, which laid out the conceptual parameters for the proceedings.

The diaspora was at the center of the symposium, and to present the Armenian experience, renowned historian Richard Hovannisian from UCLA had been invited. In his broad overview, he presented the consequences of the Armenian genocide and its effects on life in the diaspora, on the one hand, and the impact on those who lived in Soviet Armenia, on the other. Following irreparable destruction of the Armenian way of life in most of their former territories, the Armenians in the diaspora sought to maintain their collective identities in the community, and nurtured hopes of returning to the homeland one day. They did gradually heal economically and socially, despite the toll taken by assimilation. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the perspective emerged for an independent Armenian state in 1991, which offered the opportunity for an exceptional national revival, if the opportunity was properly utilized and developed.

How the trauma of genocide affected the identity of survivors was the subject of a paper by Harutyun Marutyan. Traumatized survivors often saw themselves as victims, “slaughtered sheep,” an identity which intellectuals sought to overcome. This led to the Knesset’s changing the memorial day into a date that honors heroes as well; in the Armenian case, the reference is still to genocide victims. Yet, the speaker noted, it was the memory of the genocide that instigated the struggle for democratic progress during the 1988-1990 revolution and led to the creation of the Third Republic.

And through the recent Velvet Revolution, the process of reshaping the culture of remembrance has progressed further. This was the subject of research presented by Öndercan Muti from the Humboldt University of Berlin. In a series of interviews with young Armenians (aged 19-35) in Turkey, Armenia, Lebanon, Germany and France in 2015, the research team asked how family memory had been transmitted and how the genocide affected their daily lives and political attitudes, including the way in which they commemorated the genocide. Muti reflected on the process through which the Velvet Revolution of 2018 has changed the political order and cultural and social norms. This has been reflected in the mode of commemoration and the critique by young Armenians of an identity based on victimhood.

Other aspects of the theme of identity among survivors came to light in talks by Daniel Gerson from the University of Bern, and David Leupold from the Humboldt University in Berlin. Gerson examined the experience of Holocaust survivors in Switzerland, in the context of a travelling exhibition on the subject which had met with controversy, regarding the implications of the appellation, “Swiss Holocaust Survivors.” Leupold discussed the limits of Turkey’s policy of memory regarding the genocide, on the basis of a study of local memory among the Kurdish minority in Southeastern Turkey. He argued that local memory, in the absence of recognition on a state level, may favor the emergence of “mnemonic cells of resistance,” against denialist state narratives.

Learning from the Language of Music

One most intriguing facet of the proceedings related to the role of music. Philip V. Bohlman, from the University of Chicago and the Hannover College for Music, Drama and Media, turned to music in an effort to grasp the reasons why Jewish and Armenian histories have unfolded as parallel courses. To understand what he calls the “architecture of expulsion, the geography of exile and the flight from destruction,” he listened very closely to the two musical traditions together, examining five historical moments cohabited by the two cultures. He began with biblical texts, the confluence of Jewish and Christian metaphor, then moved to the music of the diaspora and into the modern era, before reaching the post-modern moment in the current century.

A researcher from the same university, Miranda Crowdus spoke on the role of collective memory in recent popular music genres in Israel, drawing on her original research. She focused on pieces dealing with the Jewish experience, with particular stress on the role of collective memory in the construction of group identity and cohesion. Taking examples from contemporary Jewish popular music, she showed how performers draw on and illustrate simultaneous states of dispossession and collective memory. She applied her term “converging dispossessions” to describe the temporary unification brought about in the process of music-making by the evocation of collective memories and collective experiences of trauma.

Musicologist Dorit Klebe examined the influences of Armenian musical elements on Ottoman-Turkish urban and courtly songs. The subject of her specific investigation was a series of early sound documents in the Aleppo province. These wax cylinder recordings contain songs sung by a 12-year-old Armenian boy in Turkish and were made in Aleppo, which was characterized by a diversity of ethnic and religious minorities, among them Armenian and Greek Christians, and Oriental and Sephardic Jews. Thus these recordings, and others she investigated, provide material to analyze the different cultural components of the music, as to repertoire and compositional method. Klebe demonstrated some aspects of the multi-ethnic cultural environment and possible influences of specific elements of Armenian music, the “tetrachord system” as well as performance parameters such as vocal style and intonation.

As Judith Cohen, a Canadian ethnomusicologist, pointed out, exile takes many forms: it can involves entire communities, families and individuals, and can involve vast dimensions in time and space. Whether associated with expulsion or not, it is always associated with memory, and sometimes, with return. Cohen illustrated this concept through a presentation of Sephardic, specifically Judeo-Spanish (Ladino) songs of exile, expulsion, memory and return. It turns out that there are more songs about specific circumstances than about collective movements, and romantic elements may intervene, but Cohen mooted that “behind every song of personal exile, there is an awareness of collective exile, expulsion, subsequent wanderings and new homes, memory and, sometimes, on various levels, return.” In a workshop, Cohen would later present the basic genres of songs sung in Moroccan and former Ottoman lands.

Jewish musicians in the diaspora faced the question of how to deal with traditional Jewish songs, as a way of seeking and confirming identity, as musicologist Heidy Zimmerman demonstrated in a talk on three compositions, all based on Fritz Mordechai Kaufmann’s small collection, “The Most Beautiful Songs of the Eastern Jews” (Die schönsten Lieder der Ostjuden).

In the music of Armenian survivors, songs have served as means of dealing with the theme of loss of the homeland and exile. Elke Hartmann from the Free University in Berlin, explored the long tradition of the Armenian song poet, stretching back to the 12th century, and the unique symbolic language therein developed. After the 1915 genocide, many songs were updated, while others were detached from their original contexts and reinterpreted; today they are understood as allegories of the genocide experience. Hartmann traced this tradition through the lens of the experience of violence, loss and longing for a home, analyzing songs of survivors, in traditional songs, in wartime songs and in the music that developed in the new colonies of the diaspora.

In 2015 to mark the centenary of the genocide, it was music that played the leading role. It served as an “invitation to mourn with,” as Sylvia Angelique Alajaji, from Franklin & Marshall College, put it. She examined the concerts organized throughout 2015 as meditations, acts of remembrance that served to evoke and construct past traumas. These concerts, which included pieces by Western European composers alongside those by Armenians, engaged in musical discourses that broadened forms of cultural exchange, and posed the question not only of how to commemorate the genocide but who is being invited to join in the mourning; and, what it means to be an Armenian.

Life in a Minority

Two papers addressed the issue of what it is like to live as a member of a minority and how it affects one’s sense of identity. Laurence Ritter, a sociologist from Paris, presented results of her field study conducted between 2007 and 2010 on converted Armenians living in Turkey. Armenian scholar Arpine Maniero (Armenian State Pedagogical Institute and Academy of Sciences of Armenia) looked into the experiences of Armenian and Jewish students attending German universities at the beginning of the last century.

Ritter’s field study dealt with Armenian Genocide survivors and their descendants who had been forced to convert to Islam. She and her colleagues found that the experience of Hrant Dink and Fetiye Çetin served as catalysts for such “hidden” Armenians to research and rediscover their family histories. In her presentation she explored the distinction between hidden and Islamized Armenians, in light of case studies of families, and reported on changes that have occurred over the past decade, without losing sight of the dangers inherent in the currently tense situation in Turkey, with respect to this tenuous “awakening” of silenced Armenians.

In Maniero’s lecture, what was striking was the extent to which Armenian and Jewish students engaged in study within German and Russian academic institutions and circles had to fight for their national identities, against the pressures to be considered part of the dominant national elites at the time. Not only students but also professors they interacted with displayed prejudices and ignorance regarding Armenians, for example, by stating that most Armenians were engaged in trade, etc. The case of the Russian students entailed prejudices of a political nature, expressed by consular officials in Leipzig, for example, regarding Russian youth studying there. More than a comparison, the study dealt with the socialization of these two groups from the Soviet Union, who complained of discrimination in their homelands, while fighting in Germany against prejudice, or anti-Semitism.

The impact of the Armenian genocide on the perceptions of Zionists during the First World War was the subject addressed by Avital Ginat. She presented partial results of her doctoral research at the School of Jewish Studies and Tel Aviv University. In her view, the Armenian genocide constituted a turning point in the attitude of the Zionists toward the Ottoman Empire, and shifted the balance in their orientation towards the British, while generating empathy for the Armenians. Although censorship at the time makes documentation difficult, she found that as rumors about the massacres began to arrive, anxiety increased as the Ottomans continued their policy of deporting Zionist activists from Palestine. The mood turned against the Turks and Zionists saw the war as an opportunity to reorganize the region. Ginat touched on the differences within the Zionist movement regarding their cultural orientation to Germany or Britain and the controversies around the reaction to the Armenian genocide.

Genocide in Literature and Cinema

Literary works have played an important role in the culture of remembrance and in the attempts at denial as well. Birgit M. Körner of the University of Basel examined treatment of the Holocaust and the genocide in Ephraim Kishon’s “Israeli satires.” These were humorous texts, bestsellers also in Germany, which were initially seen as contributing to reconciliation between Germans and Jews. Later his stories were accused of having dissolved guilt and shame. In the 1990s, Kishon, himself a survivor, began to integrate his personal experience into his humorous poetry. It is this aspect of his work that Körner was the first to investigate, with the conclusion that Kishon was a political author and a pessimistic “humanist.”

Marc David Baer of the University of Chicago introduced an unusual approach to denialism, in a paper on the way Ottoman Jewish historiography has treated the subject. By portraying Jewish-Turkish relations in an idealized form, characterized by harmony, conviviality and a common purpose, historians have thus painted a rosy picture that excludes contradictory details and silences counternarratives. Baer views this dominant utopian narrative as a reflection of fear and anxiety at what had befallen others, and an attempt to be accepted by Muslims.

In contrast, Hervé Georgelin from the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, presented a work that represents a “rare perception of both Jewish and Armenian suffering.” This is an 800-page handwritten autobiographical fragment by Zaven Biberyan (1921-1984) that focuses on his ordeal as a young non-Muslim conscript during World War II in a forced labor battalion. The presentation shed light on the uniqueness of this work, in the author’s awareness of the collective loss suffered by the Armenians as well as the Jewish people.

Cinema is a powerful tool in shaping perceptions, and misperceptions. Lawrence Baron, formerly at the San Diego State University and the author of many books on cinema, spoke about “persistent parallels” in films about the Armenian genocide. He traced the process through which the Turkish campaign of denial enabled Holocaust films to establish the cinematic iconography and tropes employed in subsequent films about the Armenian Genocide. He showed clips from films like “The Forty Days of Musa Dagh” (1982), “Karot” (1990), “Ararat” (2002) and “The Lark Farm” (2007). In his concluding analysis of “Army of Crime” (2009) and “Remember” (2015), which deal with the anti-Nazi struggle, he raised the issue of how historical memory can be sustained and justice attained for the Armenians’ ordeal during World War I.

In the academic world, there is still a gap between historiography of the Holocaust and research into the genocide of the Armenians, as Christin Pschichholz from the University of Potsdam demonstrated. Her comparative study considered the effects of discussion about terminologies (intention, genocide), which are often subjected to political conditions, the influence of the discipline of Genocide Studies, which is still young, the integration of survivors’ accounts and the influence of the Armenian and Jewish diasporas on the respective fields of research.

Teaching the Genocide

If future generations are to maintain and transmit an understanding of these past catastrophes, so as to ensure they not be repeated, education is paramount. Thus the question of how to address these themes in the classroom had to be featured. Roy Knocke, a research assistant at the Lepsiushaus Potsdam, led a workshop on the Armenian genocide, in which he presented materials that the Lepsiushaus has developed for use in upper secondary education, and has been tested in practice. The workshop aimed at teachers and illustrated how the teaching materials allow educators to approach the subject from different perspectives.

Michael Stach, a student trainee at the State Seminar for Didactics and Teacher Training in Heidelberg, conducted a workshop on genocide and human rights as topics in teaching. His approach differed from that of Knocke, in that he located the topics in the context of artistic-creative subjects. This involves the use of texts, pictures or pieces of music as means to point out individual perspectives on moral-ethical questions and shed light on the causes, connections and effects of these topics from various viewpoints. In the workshop he presented teaching materials, especially for artistic-creative subjects, and devoted special attention to the role of the teacher in the process, with regard to competency and the sensitivity required to deal with the theme.

A round table discussion concluded the conference, on the theme, “Culture of Remembrance in the Field of Tension between Empty Promises and Ritualization.” It was a statement made by German Federal Chancellor Angela Merkel during her visit to Yerevan last August that framed the concept. “The suffering of countless Armenians must not and will not be forgotten,” she said. “Germany will make its contribution.” Those who debated the ways and means for Germany to do this included Ulla Jepke, Bundestag member for the Left Party (Die Linke), Micha Brumlik, retired professor in the education department, Goethe University in Frankfurt, Herbert Schmalstieg, former Lord Mayor of Hannover and Raffi Kantian of the German-Armenian Society.

The Role of the Arts

Literature, music and cinema utilize different artistic means to transmit a message, as speakers illustrated in diverse presentations. Conference attendees had the opportunity to experience the power of art, during film showings of “From Ararat to Zion” (2009) and “The Key from Spain: The Songs and Stories of Flory Jagoga” (2000). A special treat was offered in a theatrical production of “Das Märchen vom letzten Gedanken” (The Story of the Last Thought), based on the novel by Edgar Hilsenrath, performed by the ZAKHOR ensemble. Hilsenrath, who died recently, was a Jewish survivor who told the story of the Armenian Genocide in the form of a fable related by the storyteller Meddah to the Armenian Thovma Khatisian.

The final concert was a unique event, which brought together Armenian and Jewish musicians for the first time. Two Jewish and two Armenian ensembles presented songs from home and exile in very different styles. Opera singer and cantor Assaf Levitin, accompanied by pianists Naaman Wagner, performed songs of the Sephardic Jews in the Ottoman Empire, in compositions by Alberto Hemsi, and the Trio Kramim/Zaks presented folk-style music in contrast. The Armenian bard Stepan Gantralyan sang of the homeland and exile with his own chansons and works of other Armenian songwriters, accompanied by guitarist Emil Georgiev. And the ensemble INDIVIDUAL from Yerevan made its German debut with Armenian folk music. The title of the final concert was a statement: “We did not stand lamenting at the rivers of Bablyon.”