German-Armenian Ties Live On In Music

May/13/2016 Archived in:Culture

By Muriel Mirak-Weissbach – Special to the Mirror-Spectator

WIESBADEN, Germany, MAY 12, 2016 — When Bernhard Scheidt passed away in October last year, those closest to him thought long and hard about the most appropriate way to execute his estate. The German pianist and conductor, born in 1929 in Wiesbaden, had led a long and rich life in music, excelling as a student at the Detmold College of Music, and continuing with extensive studies under authorities like Theodore W. Adorno, whose seminar in Philosophy he attended at Frankfurt University. He studied Musicology with Gennrich und Schmitz, and Music Psychology with Prof. Albert Wellek. He was also a philologist, having studied Classical Philology with the leading authority Prof. Thierfelder at the Mainz University, and delivering a final paper on Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis.

WIESBADEN, Germany, MAY 12, 2016 — When Bernhard Scheidt passed away in October last year, those closest to him thought long and hard about the most appropriate way to execute his estate. The German pianist and conductor, born in 1929 in Wiesbaden, had led a long and rich life in music, excelling as a student at the Detmold College of Music, and continuing with extensive studies under authorities like Theodore W. Adorno, whose seminar in Philosophy he attended at Frankfurt University. He studied Musicology with Gennrich und Schmitz, and Music Psychology with Prof. Albert Wellek. He was also a philologist, having studied Classical Philology with the leading authority Prof. Thierfelder at the Mainz University, and delivering a final paper on Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis.

Schedit prepared for his career as a musician by studying composition, piano, choir conducting and orchestra conducting under Prof. Günter Bialas, Prof. Conrad Hansen, Prof. Rudolf Thomas and Conductor Karl Elmendorff, respectively. Throughout his long career as a performing musician, he accumulated a vast collection of musical scores, not only for piano, on which he performed, but for ensembles and full symphonic orchestras, which he conducted.

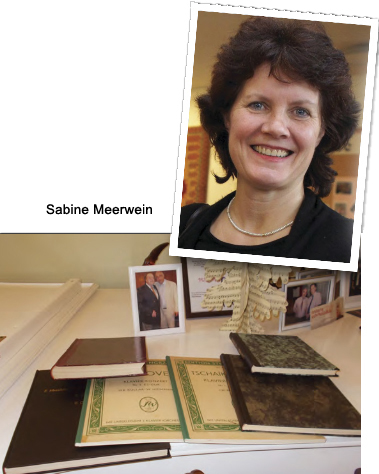

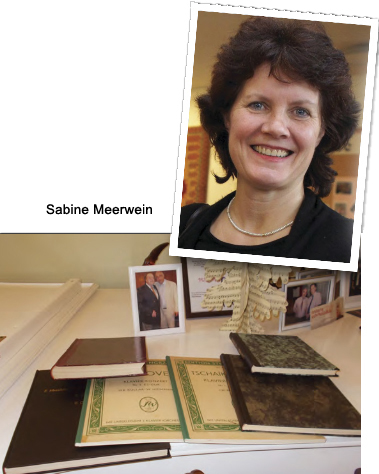

The question for Sabine Meerwein, herself a professional solo soprano and Scheidt’s long-term companion, was: on whom should she bestow the valuable scores? Who or what institution might most benefit from such a gift, and at the same time, honor his achievements and memory?

On New Year’s Eve 2015, she happened to read an article in the local newspaper, the Wiesbadener Courier, about the Mirak-Weissbach Foundation and its work in Armenia, especially in support of musical education for youth. She was especially struck by the idea of developing children through the transmission of great culture. She contacted the foundation to ask whether it might be able to identify a worthy recipient of the scores. After several discussions with Armenian musicians in Germany and, through the Armenian Embassy, contact with the Yerevan Komitas State Conservatory, it was decided to make that institution the beneficiary. On March 30, a sealed palette containing the 350 pounds of scores was picked up in Wiesbaden and began its voyage overland by truck through Turkey and Georgia to Armenia.

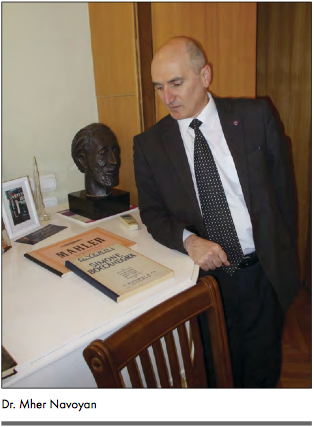

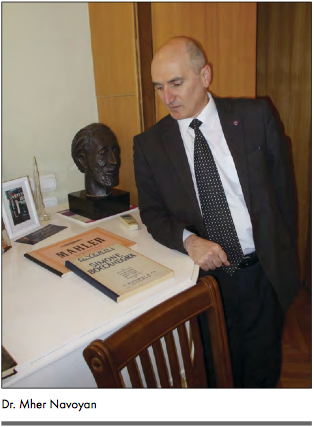

By the time my husband Michael and I arrived in Yerevan for our annual visit, the shipment was waiting in customs for the final bureaucratic procedures to be completed. On April 26, we visited the Conservatory, and later that day, the scores arrived at their final destination. Prof. Mher Navoyan, who greeted us warmly at the Conservatory, was delighted. As he had written in various communications with the Berlin Embassy and with us, the Conservatory would be most grateful to have such material for instruction.

By the time my husband Michael and I arrived in Yerevan for our annual visit, the shipment was waiting in customs for the final bureaucratic procedures to be completed. On April 26, we visited the Conservatory, and later that day, the scores arrived at their final destination. Prof. Mher Navoyan, who greeted us warmly at the Conservatory, was delighted. As he had written in various communications with the Berlin Embassy and with us, the Conservatory would be most grateful to have such material for instruction.

Navoyan, who is chairman of the Academic Council, took us on a tour of the music school, named after the famous musicologist and composer Vardaped Komitas. His presence is everywhere. In the large entry hall, a huge bust dominates the vast wall, and greets everyone who passes through the monumental doors. In every room or corridor, as well as in the library, there are portraits of him gazing down at us. In the library, we are shown the reams of musical scores that students can borrow for research or practice. Some are organized in special collections, named after the persons who have donated their libraries to the conservatory. All the works in the library, whether scores or books, are catalogued both on index cards filed alphabetically in sturdy, traditional cabinets, with pullout drawers, all made of wood, and in computers in digital form. There are separate rooms hosting the collections of recorded music, on CD’s, records and DVD’s; here students can come to listen to and view performances.

A very special department is dedicated to ethnomusicology. In the tradition of Komitas, the department head has worked for years on compiling and editing traditional Armenian songs, which have been published in separate volumes according to region of origin. She showed us several of the volumes, as well as a huge book with the musical notation system of Komitas.

When we arrived in the office of Rector Shahen Shahinyan, Navoyan showed him some of the bound volumes that we had brought with us on the plane. These were a couple of collectors’ items which had been in bad repair, due to age and had been rebound. They included works by Beethoven and Mahler, among others, in beautiful editions. Shahinyan, who is a violinist, thanked us for the gift and wanted to know more about the foundation and the donor. My husband Michael explained that we were merely the messengers; it was Sabine Meerwein who made the donation, and we arranged for the transportation and delivery.

We learned that the Armenian musical education system has deep ties to the German system. Not only Komitas, but virtually every Armenian composer visited and/or studied in Germany, establishing a tradition that goes back in time. In the modern period, when Armenia was a Soviet republic, it had established 300 music schools, which exist to the present day. These are schools where students go for individual instruction, separately from the elementary or high schools they attend. If one considers that the population is about 3 million that represents a ratio of one music school for every 10,000 citizens! The problem that music schools, including the conservatory, face is financial backing, to provide the teaching materials required. For music schools, this may be manifest in the lack of instruments. In the case of the conservatory, it is musical scores that are extremely costly. So the hundreds of quality scores donated by Meerwein are most appropriate and highly appreciated. Given the close link between the German and Armenian musical traditions, it is also fitting that the lion’s share of the scores are for works in the classical German repertoire, from Bach and Beethoven, to Brahms, Mozart, Schumann, Schubert, and so on, issued by traditional German music publishers, many of whom hold the copyrights for the original (Urtext) editions. In addition, there are works by leading French, Italian and Russian composers. On Navoyan’s suggestion, the conservatory has decided to place these scores in a section of the library named after Bernhard Scheidt.

But the reason why this estate ended up in Yerevan is a story in itself. Neither Bernhard Scheidt nor Sabine Meerwein have Armenian roots. Or rather, Armenian family roots. As Meerwein explained when she first inquired about the foundation, her great-grandfather, Gustav Adolf Meerwein, was a Protestant pastor in Germany during World War I. Though it is not clear to what extent he might have had personal contact with Johannes Lepsius, he was well aware of his efforts to save Armenians. He knew Lepsius’s Report on the Situation of the Armenian People, which had alerted German public opinion to the genocide. In 1916, Lepsius had issued a call for Germans to save Armenian orphans, essentially by paying for their freedom and placing them in Christian foster families. Great-grandfather Meerwein had answered the call, even at the personal level. He pledged that, for every grandchild he would be blessed with, he would finance the adoption of an Armenian orphan and arrange for placement in a foster family. Sabine Meerwein estimates that up to nine Armenian children found homes this way. She said she was making the donation not only in memory of Bernhard Scheidt but also in memory of her ancestor.

The other reason why she chose Armenia had to do with her own intellectual background. Though a professional singer, she also took degrees in German and Romance literature as well as Latin American Studies. Among the five to ten books that most impressed her was Franz Werfel’s Forty Days of Musa Dagh, which showed that a person could take up the cause of the homeland and in so assuming new responsibilities, develop new qualities.

As she wrote in a short biographical sketch of Scheidt, “His outstanding activity as a teacher lives on in numerous students in their public performances and concerts today. Bernhard Scheidt’s legacy lies in the transmission and communication of the German and European interpretation tradition, which he was able to pass on to his students, thanks to his personal acquaintance with extraordinary artists like Maria Callas, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Pablo Casals, Wilhelm Kempff and Pierre Monteux.” Now it may be added that he continues to transmit this tradition through the musical scores of the works of great European composers, bequeathed to Armenian students in Yerevan.

Schedit prepared for his career as a musician by studying composition, piano, choir conducting and orchestra conducting under Prof. Günter Bialas, Prof. Conrad Hansen, Prof. Rudolf Thomas and Conductor Karl Elmendorff, respectively. Throughout his long career as a performing musician, he accumulated a vast collection of musical scores, not only for piano, on which he performed, but for ensembles and full symphonic orchestras, which he conducted.

The question for Sabine Meerwein, herself a professional solo soprano and Scheidt’s long-term companion, was: on whom should she bestow the valuable scores? Who or what institution might most benefit from such a gift, and at the same time, honor his achievements and memory?

On New Year’s Eve 2015, she happened to read an article in the local newspaper, the Wiesbadener Courier, about the Mirak-Weissbach Foundation and its work in Armenia, especially in support of musical education for youth. She was especially struck by the idea of developing children through the transmission of great culture. She contacted the foundation to ask whether it might be able to identify a worthy recipient of the scores. After several discussions with Armenian musicians in Germany and, through the Armenian Embassy, contact with the Yerevan Komitas State Conservatory, it was decided to make that institution the beneficiary. On March 30, a sealed palette containing the 350 pounds of scores was picked up in Wiesbaden and began its voyage overland by truck through Turkey and Georgia to Armenia.

Navoyan, who is chairman of the Academic Council, took us on a tour of the music school, named after the famous musicologist and composer Vardaped Komitas. His presence is everywhere. In the large entry hall, a huge bust dominates the vast wall, and greets everyone who passes through the monumental doors. In every room or corridor, as well as in the library, there are portraits of him gazing down at us. In the library, we are shown the reams of musical scores that students can borrow for research or practice. Some are organized in special collections, named after the persons who have donated their libraries to the conservatory. All the works in the library, whether scores or books, are catalogued both on index cards filed alphabetically in sturdy, traditional cabinets, with pullout drawers, all made of wood, and in computers in digital form. There are separate rooms hosting the collections of recorded music, on CD’s, records and DVD’s; here students can come to listen to and view performances.

A very special department is dedicated to ethnomusicology. In the tradition of Komitas, the department head has worked for years on compiling and editing traditional Armenian songs, which have been published in separate volumes according to region of origin. She showed us several of the volumes, as well as a huge book with the musical notation system of Komitas.

When we arrived in the office of Rector Shahen Shahinyan, Navoyan showed him some of the bound volumes that we had brought with us on the plane. These were a couple of collectors’ items which had been in bad repair, due to age and had been rebound. They included works by Beethoven and Mahler, among others, in beautiful editions. Shahinyan, who is a violinist, thanked us for the gift and wanted to know more about the foundation and the donor. My husband Michael explained that we were merely the messengers; it was Sabine Meerwein who made the donation, and we arranged for the transportation and delivery.

We learned that the Armenian musical education system has deep ties to the German system. Not only Komitas, but virtually every Armenian composer visited and/or studied in Germany, establishing a tradition that goes back in time. In the modern period, when Armenia was a Soviet republic, it had established 300 music schools, which exist to the present day. These are schools where students go for individual instruction, separately from the elementary or high schools they attend. If one considers that the population is about 3 million that represents a ratio of one music school for every 10,000 citizens! The problem that music schools, including the conservatory, face is financial backing, to provide the teaching materials required. For music schools, this may be manifest in the lack of instruments. In the case of the conservatory, it is musical scores that are extremely costly. So the hundreds of quality scores donated by Meerwein are most appropriate and highly appreciated. Given the close link between the German and Armenian musical traditions, it is also fitting that the lion’s share of the scores are for works in the classical German repertoire, from Bach and Beethoven, to Brahms, Mozart, Schumann, Schubert, and so on, issued by traditional German music publishers, many of whom hold the copyrights for the original (Urtext) editions. In addition, there are works by leading French, Italian and Russian composers. On Navoyan’s suggestion, the conservatory has decided to place these scores in a section of the library named after Bernhard Scheidt.

But the reason why this estate ended up in Yerevan is a story in itself. Neither Bernhard Scheidt nor Sabine Meerwein have Armenian roots. Or rather, Armenian family roots. As Meerwein explained when she first inquired about the foundation, her great-grandfather, Gustav Adolf Meerwein, was a Protestant pastor in Germany during World War I. Though it is not clear to what extent he might have had personal contact with Johannes Lepsius, he was well aware of his efforts to save Armenians. He knew Lepsius’s Report on the Situation of the Armenian People, which had alerted German public opinion to the genocide. In 1916, Lepsius had issued a call for Germans to save Armenian orphans, essentially by paying for their freedom and placing them in Christian foster families. Great-grandfather Meerwein had answered the call, even at the personal level. He pledged that, for every grandchild he would be blessed with, he would finance the adoption of an Armenian orphan and arrange for placement in a foster family. Sabine Meerwein estimates that up to nine Armenian children found homes this way. She said she was making the donation not only in memory of Bernhard Scheidt but also in memory of her ancestor.

The other reason why she chose Armenia had to do with her own intellectual background. Though a professional singer, she also took degrees in German and Romance literature as well as Latin American Studies. Among the five to ten books that most impressed her was Franz Werfel’s Forty Days of Musa Dagh, which showed that a person could take up the cause of the homeland and in so assuming new responsibilities, develop new qualities.

As she wrote in a short biographical sketch of Scheidt, “His outstanding activity as a teacher lives on in numerous students in their public performances and concerts today. Bernhard Scheidt’s legacy lies in the transmission and communication of the German and European interpretation tradition, which he was able to pass on to his students, thanks to his personal acquaintance with extraordinary artists like Maria Callas, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Pablo Casals, Wilhelm Kempff and Pierre Monteux.” Now it may be added that he continues to transmit this tradition through the musical scores of the works of great European composers, bequeathed to Armenian students in Yerevan.