Mubarak, Morsi, and then?

Jul/10/2013 Archived in:Middle East

Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

In his famous novel Animal Farm, George Orwell satirized the outcome of the Bolshevik revolution and Stalinism. His allegorical tale showed how a gang of animals had risen up against the exploitative farmer and seized power, only to reproduce the political structures they had sought to eliminate.

Something similar may be unfolding in Egypt. After the 2011 revolution, in which mass forces mobilized nationally over 18 days and forced President Hosni Mubarak to resign, an interim military government came in, followed by the Muslim Brotherhood, led by Mohammad Morsi, declared winner of the May–June 2012 presidential elections. Now, less than a year after assuming power, Morsi, who pledged to be the president of all Egyptians, is being denounced as ‘no better than Mubarak’, even the ‘new pharaoh of Egypt’. Masses of Egyptians, including many formations that constituted the revolutionary movement that ousted Mubarak, are again taking to the streets this time demanding Morsi’s downfall, carrying posters which explicitly identify him as the reincarnation of the ousted dictator. Some are calling on the military to intervene, at least temporarily, to oversee a transition to democratic rule.

In my book on the psychological aspects of the Arab upheavals,[*] I posed the following question: are dictators, most often characterized by narcissism and other personality disorders, born or are they made? Are they doomed by traumatic childhood experiences and other social conditions to become tyrannical leaders, or are they well-meaning individuals who, once assuming political power, turn into such? Is it the case that ‘power corrupts’?

Egypt, as I witnessed during a recent visit to Cairo, provides a good case study. When he was inaugurated last June, Morsi, a leading figure of the Islamists so long persecuted by Mubarak, enjoyed public support. This was the case despite the fact that the electoral process had not been free from controversy, regarding the procedures leading to the vetting of candidates and the actual voting and tallying.

It did not take long for Morsi to fall from grace, and it was all of his own doing. His first big mistake was to overrule the Supreme Constitutional Court by calling the dissolved parliament back into session. This was the beginning of a continuing challenge to state institutions, the judiciary and military. On 22 November he issued a declaration in which he decreed (à la Mubarak) special powers to the president, i.e. to himself. Thus, all his decisions, decrees, laws etc., were protected from changes or cancellation. He also arrogated the right to take any measures he deemed necessary to protect the revolution. Although public pressure forced him to retract some of these measures, he did not fully receive the message. Instead, he rammed through a constitutional draft put together by an Islamist-dominated rump constituent assembly, announced a referendum and then new elections. Morsi proceeded to fill all possible political as well as civilian positions with people from his party, the Muslim Brotherhood, or, Ikhwan in Arabic. Egyptians call this the Ikhwanization of political and public life and compare it most unfavorably with the nepotism and favoritism characteristic of the Mubarak era. Not only has the Muslim Brotherhood put its people in ministries, but also in leadership positions of businessmen’s associations, religious and civil society organizations, etc. As Mustafa El-Labbad from the Al Sharq Center for Strategic Studies told me in an interview, through this Ikhwanization process, businessmen associated with the Brotherhood are reaping benefits as they did earlier; they are the same ‘compradors, only this time bearded.’

When I asked my Egyptian friends why Morsi was making such egregious errors, jeopardizing the power he and his movement had so long aspired to, the answer I got was: ‘it’s ideological.’ In fact, if these reports are reliable, Morsi’s Brotherhood government would like to introduce a number of demands that can only be understood as issuing from ideological concerns. Among them are the calls for eliminating a traditional Egyptian spring festival, changing the national anthem, removing music from school curricula and the like.

Egyptians of all political tendencies are demanding responsible leadership to lead the country into a new era. This means restoring public order and economic security, and finally introducing institutions of truly representative government. The number of people killed during demonstrations has been rising and the economy is on the verge of collapse. Unless the Morsi regime wakes up to political reality, it will be as readily dispensed with as was the Mubarak regime. Elections called by Morsi for Parliament cannot take place if the opposition, which, though not unified programmatically, represents a secure majority of the population, successfully leads a boycott. And if the economically and politically important governorate of Port Said, which has become a center of protest, refuses to take part, then the elections will be meaningless. Even if the polls were to be held, if only the Brotherhood and other Islamist parties were to take part, and if they were to ‘win’, that would be a Pyrrhic victory, which international bodies would have great difficulty in acknowledging.

What awaits Egypt is something that George Orwell did not contemplate in his fictional scenario: a new revolution. Although it is politically heterogeneous, the opposition can find its unity in a commitment to representative government. Civil disobedience has spread across the country, intellectuals and artists are issuing statements demanding Morsi’s resignation. And the opposition is also wielding that invincible weapon of humor. The most popular weekly television show is ‘The Program’, featuring Bassem Youssef, the Egyptian answer to American political satirist Jon Stewart. Youssef devotes most of his show to biting ridicule of Morsi and the Brotherhood. The 6 April Movement, which was at the forefront of the revolution, launched an initiative to send Morsi to the moon and collected over 20,000 signatures, placing his name on an online competition sponsored by the Axe Apollo Space Academy. Novelist Ibrahim Abdel-Meguid was quoted in Al-Ahram weekly in late February, saying: ‘If he is not getting the message from the demonstrations, and if he is not getting it from the jokes wanting to send him to the moon, then he might get it from the statements addressed to him directly.’ He added: ‘Morsi had his chance, but he failed to make anything of it. His performance shows that he is totally disconnected from what is going on in the country. He must really come from the moon, and he might as well go back there.’

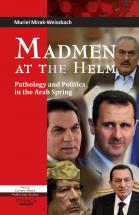

[*] Madmen at the Helm: Pathology and Politics in the Arab Spring, Ithaca Press/ Garnet Publishing, 2012/2013.