Power of Art to Move Mind and Heart:

Dink Remembered in Frankfurt

Feb/09/2014 Archived in:Armenian Genocide

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

FEBRUARY 6, 2014

By Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

FRANKFURT — Anyone who doubts the existence of a growing movement in Turkey committed to profound political reforms, emphatically including the recognition of the 1915 genocide, should reflect on the mass turnout in Istanbul on January 19, reported by the Mirror-Spectator last week. Several films circulating on the Internet (such as http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_RuZDt6wj4k and http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ELFOe-lvZ5Q) transmit a sense of the potential that this Turkish civil society movement represents, not the least because it has increasingly woven the strands of several related political demands together into one fabric. Thus, those calling for “justice” are demanding not only that Hrant Dink’s assassins be identified and prosecuted but also that the rule of law replace a system fraught with politically motivated rulings, corruption, violation of human rights and willful distortion of historical fact. From the Gezi Park protests to the ongoing upheavals triggered by the corruption scandals, a new process has been unfolding which may put the country on a course toward fundamental change.

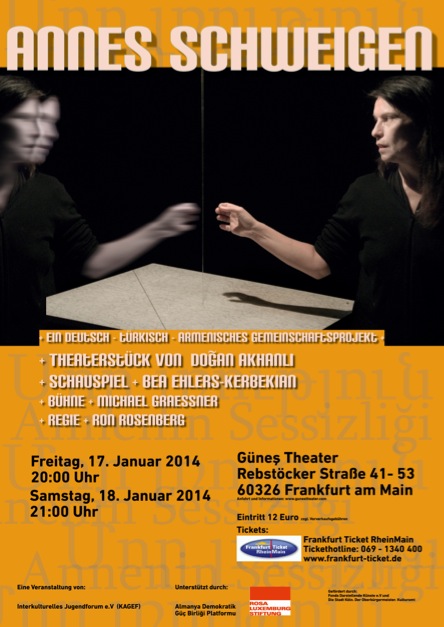

This is one of the messages that Dogan Akhanli, a Turkish-German writer, delivered in an exchange with a capacity crowd that had come to see his dramatic monologue, “Anne’s Silence,” performed in Frankfurt as part of nationwide events that weekend. Himself a victim of judicial harassment for his works on the Genocide theme, Akhanli expressed optimism that the open discussion around 1915 which is affecting ever-broader layers of the population will succeed in catalyzing a breakthrough even at the official level. Highlighting Dink’s death as the turning point in a nationwide process, he said the guilt factor had been important; “people felt guilty,” he explained, “because they had not protected him.” He added that it was significant that the murder contractors had chosen to kill not a dissident Turkish intellectual, like himself, but rather an Armenian.

Akhanli’s play deals directly with this complex. It treats the case of a Turkish girl named Sabiha who has grown up in Germany with her mother, and, though assimilated, becomes attracted to Turkish nationalist rhetoric even to the point of embracing the official version of the Genocide and speaking at a rally commemorating Talaat Pasha. When her mother dies, she discovers an Armenian cross tattooed on her chest and falls into a profound identity crisis. Hrant Dink is the figure who allows her to work through the crisis: she makes brief telephone contact with him at Agos and not long thereafter, follows live coverage of his funeral on Turkish television. The play develops Sabiha’s personal drama (which was inspired by a real-life story) and integrates documentary material around Dink, his life’s work and his untimely death. Thus the audience vicariously lives through the traumatic process, in a sense re-experiencing what hundreds of thousands of citizens in Turkey and abroad underwent in late January 2007.

The play has been performed many times in different German cities (and also in Yerevan) by Armenian-German actress Bea Ehlers-Kerbekian and has been received with enthusiasm. But in Frankfurt it detonated a minor psychological-emotional explosion, due to the fact that the overwhelming majority of the audience was of Turkish descent. The venue itself was special; the Günes Theater is a group of avant-garde artists who began as an alternative ensemble of students in Ankara in 1991. They sought to introduce new forms of communication between actors and viewers; as members of a collective, actors were at the same time authors, directors and theater owners, something utterly new in Turkey. They also performed in unconventional locations, like villages, slums, ghettoes and streets of major cities, and addressed political and social themes in contemporary Turkey. By combing aspects of Western theatre tradition with Eastern elements, including Anatolian dance, they have attracted visitors from different cultural circles.

In 1995 they began to perform in Europe while their plays were coming under increasing attack at home. Due to their critical political views, their members found themselves ever more frequently under arrest and in court. In 1998 they adopted the name Günes (for Anatolia, in Byzantine times known as ‘the land of the rising sun’) and worked both at home and in Europe until political pressures forced them to emigrate in 2002 to their current home in Frankfurt.

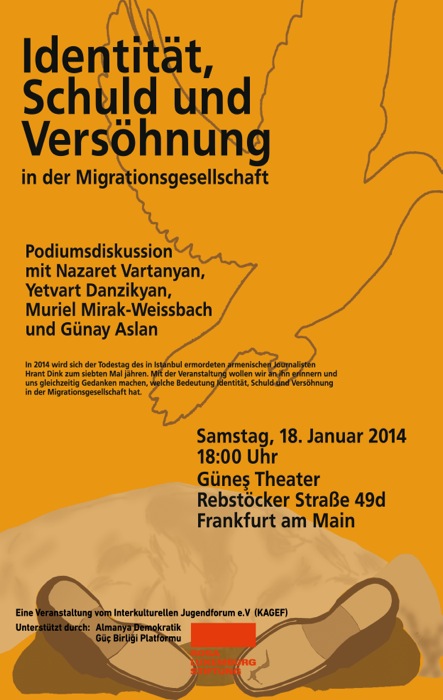

It was this Günes Theater that hosted “Anne’s Silence” on January 17 and 18, and at both performances, the audience had a chance to engage in discussion with the protagonists; the play’s author joined actress Ehlers-Kerbekian the first night for a free-wheeling dialogue with viewers and on the second a round table brought three Armenians together, journalist Yetvard Danzikyan from Agos in Istanbul, intellectual Nazaret Vartanyan, originally from Malatya now based in Brussels, and myself. The two guests from abroad presented in-depth reports on the current state of developments in the Hrant Dink case, from a legal as well as political point of view, and insisted that the full truth behind the Dink affair be brought to light. This means pursuing investigations into the political forces behind the scenes, those who planned, instigated and orchestrated the material crime. References were made to the “deep state” known as Ergenekon, but also to possible complicity on the part of persons linked to Prime Minister Erdogan’s own AKP.

This, to be sure, is the stuff of heated political debate. But the issue taken up by the panel on “Identity, Guilt, and Reconciliation in the Diaspora” is also highly personal and emotionally charged. In the session following the first night’s performance, three young Turkish women living in Germany immediately drew parallels to their own experience. The first, a college graduate who is married and works as a teacher, said the whole point about the play is identity. “I grew up here in Germany as a Turk,” she said, “and had to be German, but at one point I realized I was not fully accepted by Germans.” Then, she tended to “become more Turkish,” she said, “but that didn’t work either.” What she saw in the play about Sabiha was that it is all a question of identity: who am I really? Finally she came to see herself as someone who “is Turkish and lives in Germany.”

A friend of hers intervened to say that she, too, had been deeply moved, indeed shocked by the play. This was the first time, she said, that she had been “in an Armenian environment” — although the theatre was run by a Turkish group and most of the audience were Turkish. The presentation of the Genocide through the story of Sabiha posed a challenge to her previous views. She wondered how best to present the issue and suggested that one might be able to produce empathy on the part of Turkish viewers, if one also referred to massacres victimizing Muslims, for example in Srebrenica. (This, the moderator noted, was not comparable to the Armenian case, because the Srebrenica genocide has been recognized as such.) Yet another aspect emerged when she reported that just six months ago, she learned from her 91-year-old grandmother in Turkey that her mother (i.e. the girl’s great-grandmother) had been Armenian. Like countless others who have made such discoveries in the recent period, she wants to research her family history now, to find out the truth. According to the grandmother’s account, some survivors in the family had migrated to America, but she didn’t know their names or where they had landed. Yet another young Turkish girl spoke of the need for empathy, and raised the question: is forgiveness also possible?

For Bea Ehlers-Kerbekian, such candid, spontaneous reactions were proof positive that the play had delivered its message and had its desired impact. “They have taught me even more about who Sabiha in the play really is,” she later remarked, “and what her life in Germany is like.”

Author Akhanli was positively surprised to witness such genuine reactions. Another passionate intervention came from a woman who had discovered her Armenian roots just some years back and had been traumatized by the social problems she encountered as a result: Turkish friends who no longer considered her one of their own and Armenians who rejected her as a Turk. All these and many more observations drove the point home: In the current juncture, Turkey — its political elite as well as its population — is going through a healthy and unprecedented crisis, a crisis of identity for the nation and for each individual.

One participant put it this way: “If what the play presents is true, if the Turkish Republic was founded on a lie, if ‘Turkishness’ is a false ideology, what then can our identity be?” This raises the fundamental question: what is identity? Is it based on language, or ethnicity? On “blood-and-soil” ideology or territorial domains? On religion or history? On gender? Or something more?

Akhanli’s play is a brilliant work of art which, in a highly condensed form, thrusts the identity issue to the forefront. It succeeds in presenting the Armenian Genocide as historical fact, mediated through the subjective experiences of multiple actors — the perpetrators and their progeny among the denialists, the victims among the Islamized survivors, the unknowing descendants of the hidden Armenians, the uninformed neighbors and friends, and the courageous individuals like Hrant Dink inside Turkey and abroad who have dared break the taboos reigning since the founding of the Republic.

All relevant political and psychological issues are touched upon in the play, not as dogma but as art. And therein lies its secret power. In response to one questioner who asked why drama should be the vehicle, Ehlers-Kerbekian explained that it is uniquely through art that one can address such profound matters, because art — in this case, drama — appeals not only to the intellect but to the emotions, the heart. In this case she spoke of catharsis. During the second performance, the actress achieved such an intensity of intellectual-emotional tension that very few in the audience — whether men or women, Turkish, German or Armenian — could hold back their tears.

(For a full review of the play, see „German-Turkish-Armenian Project Dramatizes Search For Identity,” Armenian Mirror-Spectator, December 22, 2012, p. 14 (http://www.mirrorspectator.com/pdf/122212.pdf))

- See more at: http://www.mirrorspectator.com/2014/02/06/power-of-art-to-move-mind-and-heart-dink-remembered-in-frankfurt/#sthash.edUFvZVj.dpuf