Architecture as Witness to Genocide

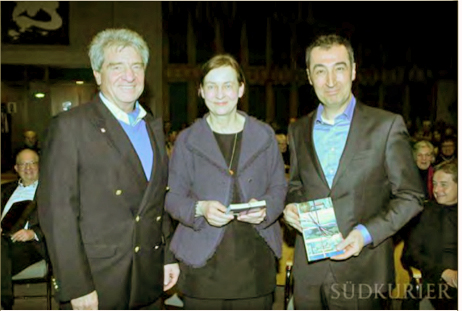

From left, Frank Hämmerle, Dr. Regine Randhover, German-Armenian Society board member and

scholar who introduced the Exhibition, and Cem Özdemir (Photo Courtesy of Süd Kurier)

By Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

Special to the Mirror-Spectator – FEBRUARY 16, 2017

CONSTANCE, Germany — For almost a decade, a photographic exhibition on the “Nakba,” the expulsion of the Palestinians from their lands in 1947-48, has been travelling around Germany, and in virtually every site, the organizers from the Association of Refugee Children in Lebanon have run up against opposition. Pro-Zionist groups have mobilized to have the exhibition rooms — often in universities — cancelled, arguing that the exhibition is anti-Israel, or even anti-Semitic. The reason? According to official Israeli historiography, there were no expulsions, killings or seizure of Palestinian lands. Some say the Palestinians as a people never existed, or if they did, not in that geographical location.

Armenians in Germany are experiencing something very similar. It is not the Zionists but the pro-Turkish lobby that is intervening to protest a travelling exhibition that documents what happened to the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in 1915. The show, titled, “1915-2015: Armenian Architecture and Genocide,” is organized by the German-Armenian Society, and has appeared in almost a dozen cities thus far. Last week the local authorities of Constance, a city in southern Germany, held the opening in an atmosphere of extreme polarization. The Turkish General Consul from Karlsruhe had sent a letter to the Constance administrative body, expressing the disappointment of the Turkish community in Germany with the event.

In his opening remarks at the vernissage on February 8, the head of the Constance local administration, Frank Hämmerle, reported his amazement, that he had been criticized by both Consul Cem Örnekol and a local Turkish-German community group. “The Consul General,” he said, “writes that the exhibition provoked ‘deep disappointment’ in him, and he pointed to the fact that this exhibition may have a negative impact on ‘the city of Constance,’” Hämmerle stressed, “in its desire to establish a partnership with a Turkish city.” The formulation has the ring of a warning to it. The response of Hämmerle and his archivist Wolfgang Kramer, who organized the event, was to place the consul’s letter in a glass showcase, and put it on exhibit as well. “We want to make clear where intolerance and hatred lead,” said Hämmerle. He specified this was not an attempt to cast blame, but rather to sharpen awareness. Every society, he said, should face up to its own history. In addition, “It is a matter of freedom on opinion.” He expressed his shock at learning that even some Armenians living in the area on the Lake of Constance had sought to cancel the exhibition out of fear that they and/or their relatives in Turkey might be affected. “Does Mr. Erdogan’s hand reach as far as Constance?” Hämmerle asked.

Cem Özdemir, co-chair of the Green Party and a member of the Bundestag (Parliament), was a guest speaker, and he minced no words. “We have to talk about this,” he said. Referring to the Bundestag’s recognition of the genocide last June, which he helped push through, Özdemir said, “I regret that it took more than a year … but then, there is clearly never a ‘right time’ to talk about genocide. There are always reasons found to postpone it.” He said he was all the more happy that it passed, stressing that the Bundestag had “done what it does not do every day,” i.e. passed the resolution almost unanimously in an all-party effort.

In a brief film interview with Günther Köhler, Özdemir spoke of his own personal experience with the genocide issue. “My parents came from Turkey,” he began. “Turkey, whose predecessor, the Ottoman Empire, was a multicultural empire, in that people of very different backgrounds lived there. Before the first Turks, the Seljuks, stepped foot onto Anatolian soil, there were many Christians living there, Jews who lived there, and who later settled there after the Reconquista.… When you look at Turkey today,” he said, “there is not so much left, and they did not simply vanish into thin air. This naturally raises questions and I, as someone who was born and raised here [in Germany], had these questions, but didn’t get any real answers to them. And that is what led me to take up this matter.”

The Photographic Record

The organizers in the German-Armenian Society chose to place architecture in the center of the exhibition, and to display photographs on 22 very large panels that document Armenian life before 1915. Like postcards of the period, which have also been displayed in recent years, these photographs show how Armenian architecture left its mark on streets and cities. The questions Özdemir asked himself are those raised and answered in the display.

First, to inform those not familiar with Armenian history, the pictures show families, homes, places of employment, as well as schools, churches and cloisters as they appeared before 1915, accompanied by texts giving facts and figures, for example, that according to the Constantinople Patriarch in 1913/1914, there were about 5,000 Armenian schools, churches and cloisters.

The deportations and massacres are documented in photos as well as eye-witness reports, by US Ambassador Henry Morgenthau, for example. Another section focuses on the destruction of the living space of the Armenians in all areas: confiscated living quarters and places of employment, whether for handwork or manufacture; the destruction or decay of churches and cloisters, as well as their conversion into mosques, if not barns, storage rooms, garages, gyms or even prisons. In some cities, like Sivas, urban expansion has replaced the bishopric and cathedral with shopping centers.

If many cloisters were blown up (Khtzkonk cloister) or razed (Karmravor cloister, Surp Asdvadsadsin), others were destroyed and their building material recycled to construct homes or mosques (Surp Garabed cloister in Mush). Special attention is paid to the region of Lake Van, where cloisters served as cultural centers in the 5th century. About 250 cloisters, churches, forts and the like were counted before 1915.

Parallel to the physical destruction or conversion of architectural monuments, the cultural identity of Armenian life was eradicated, as names of places, buildings and persons were changed. Beginning under Sultan Abdülhamid II, the photographic evidence shows that this Turkification process affected not only place names in Armenian but also in Greek, Aramaic, Kurdish and Arabic. Famous architectural monuments like the Kars cathedral or the ruins of Ani, the “city of1001 churches,” are not identified as Armenian. (The parallels to Palestinian life in present-day Israel are striking, as place names have been systematically changed.)

Recovering the Past

Many Armenians, including myself, have had the privilege of visiting historic Armenia under the expert guidance of Armen Aroyan, and seeing for themselves what once was, and what has become of that past. For those, especially non-Armenians, who have not travelled there and who have no inkling of what people and culture lived there, this exhibition is a treasure. And the frantic attempt on the part of certain Turkish institutions to sabotage it only underlines the political and educational value of the display. (The same should be said of the “Nakba” exhibition, whose organizers continue to move it from city to city despite massive pressure.)

Relations between Turkey and Germany have soured especially since the Bundestag’s genocide resolution went through. And the internal dynamic has only exacerbated matters. For Cem Özdemir, “Things in Turkey are going in the wrong direction.” Speaking to an interviewer in Constance, he explained, “Turkey had been more advanced; years ago one could discuss many of these issues, the first churches were restored, some property was returned, but now with the internal political discourse becoming more rigid, this has had a dramatic impact also on this question.” This includes the Kurdish issue, he added. “It is difficult to deal with the very darkest moments of one’s history, with the genocide; I regret this very deeply,” he said, “but I believe as long as Turkey continues on this path toward an authoritarian state, we should not have illusions. Also the Armenian issue will not be handled with the necessary attention in Turkey. To do so requires the courage of democracy and the courage to display openness. The Turkish state leadership at the current time does not have this.”